The Coming Week’s Daf Yomi by Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz

This essay is based upon the insights and chidushim (original ideas) of Talmudic scholar Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, as published in the Hebrew version of the Steinsaltz Edition of the Talmud.

Masechet Zevachim: Introduction

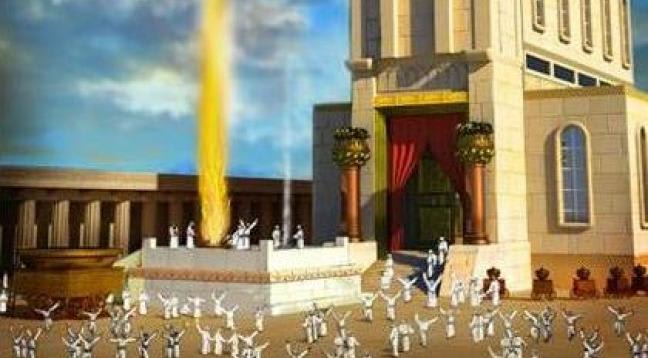

The sacrificial service in the Temple – referred to simply as avodah, or “service” by the Sages – is one of the foundations of the Torah, and is considered one of the pillars upon which the world stands (see the Mishnah in Masechet Avot 1:2). Even after the destruction of the Temple, when the laws of the sacrificial service became relevant only for Messianic times, the Sages continued to discuss these topics to the extent that we have an entire Order of Talmud – Seder Kodashim. Although we only have Gemara on Seder Kodashim in the Babylonian Talmud, there is evidence from the works of the rishonim that there was Talmud Yerushalmi on it, as well, that was not preserved and appears to have been lost entirely.

Masechet Zevachim offers a broad explication of the laws of sacrifices that are brought from live animals – that is, fowls and animals – while meal offerings have a tractate, Masechet Menahot, devoted to those laws. The main topics discussed are the sacrifices themselves – how they are prepared, where they are brought, what would disqualify them – but not what animals are brought for each sacrifice. That topic is dealt with in other tractates, and not only in Seder Kodashim. For example, Yoma and Pesahim introduce the sacrifices of Yom Kippur and Pesach; Nazir introduces the sacrifices brought by a Nazirite, etc. Our tractate also does not discuss the order of the sacrificial service in the Temple, neither on a daily basis (those laws appear in Masechet Tamid) nor on holidays (those appear in tractates devoted to individual holidays).

Nevertheless, given that Masechet Zevachim is the first tractate in the Order of Kodashim, and that the laws of the sacrifices that are dealt with are among the most basic activities in the Temple, the tractate includes a number of general issues that will serve as a foundation for the other tractates in Kodashim, each of which will be taken up and discussed as appropriate.

Although the laws of the sacrifices are dealt with at length in the Torah – mainly in Sefer Vayikra, but in Shemot, Bamidbar and Devarim, as well – as is the case throughout the Torah, the laws are not presented as general principles in a set, orderly manner, rather they appear as descriptions and as individual laws. Even in places where the Torah offers a lengthy description of the requirements of the sacrifice, there is not enough information for us to understand what must actually be done without the traditions of the Oral Torah and the explanations of the Sages on these matters. Furthermore, the Torah only instructs what must be done, without devoting attention to questions of how to deal with situations where the activities were not done according to the requirements, Therefore, Masechet Zevachim takes on the task of offering general, organized principles that govern the sacrificial service, and explain what to do when mistakes are made.

Sacrifices – meaning sacrifices from living creatures – can be organized in a number of ways.

One straightforward distinction is between sacrifices from animals and from fowl, both of which are dealt with in this tractate. Similarly, we can divide animal sacrifices based on the type of animal – larger cattle, such as cows and bulls or smaller livestock, such as goats and sheep – based on the age of the animal, or based on the sex of the animal. Some sacrifices can be brought from any of these animals, while some are limited to specific animals or types of animals.

Another type of distinction is based on the level of holiness of the sacrifice. Is it kodashei kodashim – the holiest of sacrifices – or kodashim kalim – sacrifices on a lower level of holiness?

Sacrifices are also divided up based on time and place. Some sacrifices can be slaughtered only in the northern part of the Temple courtyard, while others can be killed anywhere in the courtyard. The blood of some sacrifices is sprinkled in the Holy of Holies, in others it is sprinkled on the Golden altar outside of the Temple. Even on the altar, it may be placed on the upper part of the altar or the lower part; it may be put on each of the four “horns” of the altar or on two of the corners. At the same time, some sacrifices can be brought at any time, others according to the individual need of the person bringing the sacrifice, while others must be brought only at specifics times.

Some sacrifices are not eaten at all, others are consumed by the kohanim, while some have parts that are given to the owner of the korban (sacrifice) to eat. Of those that are eaten, some must be consumed on the day that they were brought while others can be eaten on the following day, as well.

There are four basic avodot – activities – that must be performed for each animal sacrifice –

- Shechita – slaughtering the animal (this need not be done by a kohen)

- Kabalat ha-dam – collecting the blood at the time of slaughter

- Holachah – carrying the sacrifice to the altar

- Zerikat ha-dam – sprinkling the blood on the altar.

Sacrifices brought from fowl involve just two such avodot –

- Melikah – killing the bird

- Netinat ha-dam – placing the blood on the altar.

Most of the sacrifices involve burning parts of the animal on the altar.

The issues of time, place and the order of the service are of utmost importance when bringing sacrifices. In some cases, any change from the required practice will invalidate the sacrifice, although in some cases certain changes will be acceptable ex-post facto.

A unique set of laws that apply to the sacrificial service involve the fact that sacrifices may become disqualified not only by inappropriate actions, but even by means of inappropriate thoughts.

Two cases of inappropriate thoughts apply to all sacrifices:

- Someone who thinks that he will bring the sacrifice or eat it after the appropriate time creates a situation of pigul, for which he will be liable to receive the punishment of karet if he eats it,

- Someone who thinks that he will bring the sacrifice or eat it outside of the place where he is required to eat it, will disqualify the sacrifice.

There are other cases of inappropriate thoughts, such as a case where the person intends to bring the animal for the wrong sacrifice or the wrong person. For most sacrifices, if such a mistake were made the person would not fulfill his obligation.

Finally, since Masechet Zevachim deals generally with the sacrificial service it also touches on such topics as the prohibition against bringing sacrifices outside of the Temple, which serves are a contrapositive to the main topic of this tractate – the commandment to bring sacrifices in the Temple.

Zevachim 2a-b: Proper intent – in sacrifices and in divorce

The first perek of Masechet Zevachim deals with one main issue: situations where a sacrifice was brought properly, that is, all of the required actions were done according to the law, but improper thoughts were made at the time that the sacrifice was brought. According to the Mishnah, there is a Biblical prohibition against such thoughts, but we need to examine the impact that such thoughts will have on the sacrifice and its validity.

The first Mishnah teaches that if a sacrifice were brought she-lo lishmah – with the wrong intention in mind, e.g. the animal had been set aside for one type of sacrifice but was slaughtered for a different sacrifice – it remains a valid sacrifice, although it does not count and the owner will need to bring another sacrifice to fulfill his obligation.

In the Gemara, Ravina quotes Rava as teaching that the Mishnah implies that the sacrifice is not sufficient because he had the wrong intention. If, however, he did not have any specific intention, then the sacrifice would work. Rava contrasts this with the law regarding a divorce, where the requirement is that the divorce be written lishmah – with specific intent for the man and woman who are getting divorced. In the case of divorce, if there was no specific intent, the get – the divorce document – will not be valid.

Rava explains the difference as follows. In the case of sacrifices, the animal has been consecrated already, so a lack of specific intent would leave it in its current situation, as a valid sacrifice. In the case of divorce, however, we do not assume that a married woman is to be divorced, so without specific intent, the get will have no meaning.

Ultimately both the sacrifice and the divorce document need intent. The difference between them is that the intent has already been determined in the case of the sacrifice, and it will remain in place so long as no one changes the situation, as opposed to writing a divorce, where without specific intent, the document does not relate to the woman involved.

Zevachim 3a-b: Thinking good thoughts about sacrifices

As we learned on yesterday’s daf one of the essential elements of a sacrifice is that all the parties involved have the appropriate thoughts at the time that the sacrifice is brought. Therefore, if the owner thinks that the sacrifice is being brought for a different korban than the one it was set aside for, the sacrifice does not count and he must replace it with another. On today’s daf the Gemara brings a statement made by Rav Yehuda quoting Rav who taught that although switching sacrifices would invalidate the korban, if the owner’s intent was that the animal would be slaughtered for chullin – not for a korban but for mundane purposes – then the sacrifice would remain valid. Apparently only a similar use will invalidate the korban; a totally dissimilar use will allow the sacrifice to remain valid.

As on yesterday’s daf, the Gemara contrasts this ruling with the laws of gittin – Jewish divorce law. If, in a parallel case, a get – a divorce document – was written without specific intent, or even if it was written with the intent that it be used for a non-Jewish woman, it will be invalid. In such a case, where writing the get with a non-Jewish woman in mind would be a dissimilar use, we see that the document is not valid!

In answer, the Gemara says that dissimilar use is the equivalent of having no specific intent. As we learned on yesterday’s daf, having no specific intent will not affect the validity of a korban that has already been set aside as a sacrifice, but it will not allow for the creation of a divorce document.

The Chazon Yechezkel and other commentaries note that this discussion points to the fact that the problem with an incorrect thought when a sacrifice is brought does not stem from having removed the original sanctity from the korban – for if that were so, intending to slaughter the sacrifice for mundane use should do that, too. Rather the problem stems from the fact that the incorrect thought attempts to establish this sacrifice for a new and different purpose. This can only happen if it remains in the framework of a sacrifice.

Zevachim 4a-b: The purpose of a peace-offering (shelamim)

In the previous dapim of Masechet Zevachim we have seen the importance of the idea of lishmah – that the sacrifice must be brought with the appropriate intent, so that at the time when it is sacrificed the owner has in mind what the sacrifice is and why it is being brought. The Gemara on today’s daf searches for a source for that law.

The passage that is brought as a source is from Sefer Vayikra (3:1) where the Torah commands ve-im zevah shelamim korbano – that if the sacrifice being brought was a korban shelamim – indicating that the sacrifice must be slaughtered with the specific intention that it was a shelamim. The Gemara continues with a discussion of how we can learn that each of the other avodot – activities of the sacrificial service aside from Shehitah (slaughtering the animal) – also must be done with the proper intent, and finds specific sources for

- Kabalat ha-dam – collecting the blood at the time of slaughter

- Holachah – carrying the sacrifice to the altar

- Zerikat ha-dam – sprinkling the blood on the altar.

This entire discussion relates specifically to the shelamim sacrifice. Ultimately the Gemara will derive the need for all of the sacrifices to be brought lishmah from the passage in Vayikra (7:37) where the Torah concludes the laws of the sacrifices and enumerates the olah (burnt-offering), mincha (meal-offering), chatat (sin-offering), asham (guilt-offering), milu’im (consecration-offering) and the shelamim, all in one verse. This is understood to connect them and impose the general requirements of one on all of them.

The shelamim sacrifice is most often translated as a peace offering. Most often the korban shelamim was brought as a voluntary gift (with the exception of the shelamim that was brought as a korban hagigah on one of the festivals and a few other cases). A part of each such offering was burned on the altar, a part was given to the priests and the rest was eaten by the person who brought the sacrifice together with his family anywhere in the city of Jerusalem. As it was divided between its owner, the kohanim and the altar, it is viewed as a sacrifice of peace, since it meets the needs of all involved.

Zevachim 5a-b: Sacrifices that do not serve their true purpose

Although we have learned that a sacrifice must be brought lishmah – with the proper intention – the first Mishnah (2a) teaches that if a sacrifice were brought she-lo lishmah – with the wrong intention in mind, e.g. the animal had been set aside for one type of sacrifice but was slaughtered for a different sacrifice – it remains a valid sacrifice, although it does not count and the owner will need to bring another sacrifice to fulfill his obligation.

Resh Lakish is disturbed by this ruling, and argues that if the korban can be brought, it should serve its purpose, and if it does not serve its purpose, then why should it be brought? That is to say, if the need for lishmah is only an ideal, but the sacrifice remain valid, then why would it not fulfill its purpose? And if it is essential to have the sacrifice brought lishmah, then a korban without proper intent should be disqualified entirely.

In response Rabbi Eliezer points to a Mishnah from Masechet Kinim (2:5) – which deals with sacrifices brought from fowl – that teaches that if a woman who has given birth brings her chatat and then dies before bringing her olah, then her children will have to bring the olah on her behalf. If, however, she has brought her olah, the children will not bring her chatat – even if it was already set aside during her lifetime – since she is no longer alive to receive that atonement for which the sin-offering is brought. He argues that it is clear from here that the olah will be brought as a korban, even though its owner is not here to benefit its sacrifice.

Ultimately Reish Lakish agrees that sacrifices must be brought even if they will not serve their ultimate purpose, based on the passage in Sefer Devarim (23:24) that obligates a person to ensure that the vows he made to God are fulfilled.

A woman who has given birth is obligated to bring two sacrifices – an olah (a lamb as a burnt-offering) and a chatat (a pigeon or dove as a sin-offering) – see Sefer Vayikra (12:6-8).

Zevachim 6a-b – The purpose of a burnt-offering (olah) – I

When someone violates a negative commandment, the Torah offers various punishments when it was done on purpose, and, under certain circumstances, requires a korban chatat – a sin offering – as atonement when it was done by accident. For neglecting to perform most positive commandments we do not find any punishment in the Torah, nor is there any requirement to bring a sacrifice for atonement. Nevertheless, the Sages suggest that the korban olah – the burnt offering – serves to atone for the neglect of a positive commandment.

The Gemara on today’s daf asks whether this sacrifice would atone even for missing positive commandments after the animal was set aside to be an olah, or is it limited to those transgressions that took place prior to the animal’s consecration. The Gemara explains the question: Is the olah similar to the chatat that only affects transgressions that had already taken place, or should we say that the laws of a chatat are unique in that a single chatat must be brought for every transgression, while the olah offers atonement for all of the times that the individual missed opportunities to perform a positive commandment.

Although the Gemara does not reach a conclusion regarding this question, it is important to help us understand the underlying principles of this korban olah. The korban olah does not serve the identical purpose of the korban chatat. It is not a sacrifice of atonement for a particular sin, rather it serves as a gift to God that repairs a broken or distressed relationship with Him (see this point developed further on tomorrow’s daf. Thus, the olah sacrifice is not connected to a single mitzvah, and it can serve to repair the damage done by neglecting any number of positive commandments.

As Rashi points out, the question in our Gemara does not relate to the time after the olah has already been sacrificed, when it certainly cannot serve to atone for what happened in the past. Still, when the positive commandment was neglected before the sacrifice was actually brought – even if the animal had already been set aside – it is possible that the olah could serve to repair the covenantal relationship even with regard to that transgression.

Zevachim 7a-b: The purpose of a burnt offering (olah) – II

Why is a korban olah – a burnt offering – brought?

Rava explains that it is a gift to God and does not come to effect atonement. The Gemara supports this by quoting a baraita in which Rabbi Shimon teaches that whenever both a chatat – a sin-offering – and an olah need to be brought, the chatat is always brought first. This is like a defense attorney who first appears before the king to argue on his client’s behalf, and only after the offence is forgiven does the client appear with a gift for the king.

Rava’s teaching stands in apparent contradiction to the Gemara on yesterday’s daf (=page), which taught that the olah sacrifice served to atone for mitzvot asei – positive commandments – that were not performed. There is no punishment in the Torah for neglecting to perform a positive commandment, so the Gemara claimed that this sacrifice served as a kappara – an act of atonement – for it.

In his commentary on the Torah (Sefer Vayikra 1:4) the Ramban explains that when someone intentionally neglects to fulfill a positive commandment, even though there is no punishment, nevertheless there is a break in the relationship between the sinner and God. The korban olah, brought as a gift to God, serves to repair the relationship, and is therefore seen as offering atonement. From Rashi it appears that he believes that simple teshuva – repentance – suffices to fully erase the sin of neglecting to perform a mitzvat aseh. The intention of the Gemara is to say that the olah sacrifice would allow such a person to be welcomed before God when he desires to approach Him (see a similar use of the term kapparah in Bereshit 32:20 when Yaakov approaches his brother Esav preceded by many gifts).

The olah is usually referred to as a burnt-offering as it is totally consumed on the altar in the Temple.

Zevachim 8a-b: Bringing a Passover sacrifice during the year

We learned in the first Mishnah in Masechet Zevachim (2a) that if the korban Pesach – the Passover sacrifice – were brought at the proper time – the 14th day of Nissan – with improper intent, it will not be acceptable. The Gemara on today’s daf (=page) quotes a baraita that clarifies this matter further. According to the baraita, a korban Pesach that is brought at the proper time with proper intent will be valid, but if it is brought with improper intent it will not be acceptable. If the korban Pesach was brought on a different day of the year, however, it will be an acceptable sacrifice if it was done without intending it as a korban Pesach. If the person meant to bring it as the korban Pesach, then it would be invalid as a sacrifice.

The Gemara continues and explains that since the korban Pesach can only be brought on a specific day of the year, if an animal that was consecrated for that sacrifice was brought on a different day, and the owner did not intend for it to be a korban Pesach, then it is acceptable as a korban shelamim – a peace-offering (see above, daf 4).

In the continuation of the Gemara we find different passages that are brought as sources for the idea that the korban Pesach can be brought as a korban shelamim if it is sacrificed on a different day during the year without the intention that it should be a korban Pesach. At no point, however, does the Gemara offer a source for the fact that if the person’s intention was that it should be a korban Pesach it is invalid. Rashi suggests that since the date of the Passover sacrifice – the afternoon of the 14th of Nissan – is repeated several times in the Torah, it should be understood to mean that any other day is invalid. Tosafot brings a slightly different approach in the name of the kuntrus (which usually refers to Rashi), based on logic rather than on the Biblical passages. He argues that it is clear that the only possible date when the korban Pesach can be brought in a meaningful way is on the holiday of Pesach, and not on any other day of the year.

In addition to his monumental translation and commentary on the Talmud, Rabbi Steinsaltz has authored dozens of books and hundreds of articles on a variety of topics, both Jewish and secular. For more information about Rabbi Steinsaltz’s groundbreaking work in Jewish education, visit www.steinsaltz.org or contact the Aleph Society at 212-840-1166.

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.