The Coming Week’s Daf Yomi by Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz

This essay is based upon the insights and chidushim (original ideas) of Talmudic scholar Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, as published in the Hebrew version of the Steinsaltz Edition of the Talmud.

Zevachim 9a-b: Bringing a sin-offering on behalf of Nachshon

The Gemara on today’s daf offers four different versions of a teaching that Rav quotes in the name of Mavog:

- If a sin-offering is brought for the purpose of being a chatat Nachshon – i.e. to be like one of the sin-offerings brought by the princes on the occasion of the consecration of the Tabernacle in the desert (see Sefer Bamidbar chapter 7) – it remains a valid sacrifice that serves its original purpose. Rashi explains that since the sacrifice was not brought in order to affect atonement for anyone (the original sin-offerings at the consecration of the Tabernacle were more of a gift than an ordinary sin-offering), we view them as a standard chatat that remains valid.

- If a sin-offering is brought and the owner says that its purpose is to serve as atonement for Nachshon, it remains a valid sacrifice. Since a sacrifice cannot act to bring atonement for a dead person, it is not considered to have been brought for a foreign purpose or a different owner, and it remains valid.

- If a sin-offering is brought and the owner intends it on behalf of someone who is obligated in a sin-offering like Nachshon (e.g. a Nazirite, who, like Nachshon brings a sin-offering as a gift, rather than because he needs atonement), it is valid. Since Nachshon’s sin-offering served the purpose of a gift, it matches the sacrifice that this person needed to bring.

- If a sin-offering is brought for the purpose of being a chatat Nachshon, it is an invalid sacrifice. Since Nachshon’s sacrifice was more of an olah – a burnt-offering brought as a gift – than it was a sin-offering, such a sacrifice appears to be brought with improper intent.

The confusion regarding this teaching notwithstanding, given the fact that Rav quotes Mavog as an authoritative source indicates that he was a scholar. It is likely that he was from the Syrian city of Mabbog, now known as Mambidj.

Zevachim 10a-b: Dividing the altar in half

According to the Mishnah (2a), if a sacrifice was brought with the wrong intention – e.g. where, at the time of slaughter, the owner thought that this animal was to serve as a different sacrifice – it remains a valid sacrifice, although it does not count for its original purpose and, if he was obligated to bring a korban, the owner will have to bring another sacrifice. The only exceptions are the Passover sacrifice (korban Pesach) and a sin-offering (korban chatat), which must be brought with the proper intent. Rabbi Eliezer argues that a korban asham – a guilt-offering – also must be brought with the proper intent. His reasoning, as it appears in the Mishnah, is that the asham is similar to the chatat in that they both come to atone for sin. Therefore, if the chatat must be brought with the proper intent, the asham must be brought with the proper intent, as well.

On today’s daf, a baraita is brought where we find an expanded version of this argument. Rabbi Yehoshua responds to Rabbi Eliezer that a korban chatat and a korban asham are not similar and cannot be compared, since the blood from the sin-offering is sprinkled on the upper part of the altar.

The altar was divided into two – an upper half and a lower half. As Rashi explains, in the mishkan (Tabernacle) the altar had a ledge halfway up (see Shemot 27:5) while in the Temple the altar was divided by hut ha-sikra – a red line that was drawn in order to divide the top half of the altar from the bottom half in order to show where the blood of the different sacrifices had to be sprinkled. Of all the sacrifices, only a sin-offering brought from an animal and a burnt-offering brought from fowl had their blood sprinkled on the upper part of the altar; blood from all other sacrifices was sprinkled on the lower part of the altar.

Ultimately, Rabbi Eliezer explains that his ruling stems from the passage in Sefer Vayikra (7:7) that juxtaposes the sacrifices of the chatat and the asham, indicating that their laws parallel one another. This juxtaposition, referred to as a hekesh, is accepted by all. Those who disagree with Rabbi Eliezer argue that it comes to teach us a different law that is shared by these two sacrifices – that each of them needs semicha, i.e. that the owner must place his hand and lean on the sacrifice as it is being brought.

Zevachim 11a-b: A special day in the house of study

As we learned in the first Mishnah (daf 2a), if a sacrifice were brought she-lo li-shmah – with the wrong intention in mind, e.g. the animal had been set aside for one type of sacrifice but was slaughtered for a different sacrifice – it remains a valid sacrifice, although it does not count and the owner will need to bring another sacrifice to fulfill his obligation. The only exceptions are the korban Pesach (the Passover sacrifice) and a korban chatat – a sin-offering – which must be brought with the proper intent.

Shimon ben Azzai concludes the discussion by saying “I have a tradition from the 72 elders, on the day that Rabbi Elazar ben Azarya was appointed head of the yeshiva, that all edible sacrifices that were brought without proper intent are valid, although they will not count towards the obligation of their owners, with the exception of the korban Pesach and korban chatat, which must be brought with the proper intent.” The Mishnah points out that Shimon ben Azzai’s teaching places a korban olah – a burnt offering – in the same category as the korban Pesach and the chatat, inasmuch as it is not an edible sacrifice (it is entirely burned on the altar, and none of it is eaten). Nevertheless, the Sages of the Mishnah reject his tradition.

When Shimon ben Azzai refers to the day that Rabbi Elazar ben Azarya was appointed head of the yeshiva, he is talking about a famous situation described in Gemara Berakhot (27b-28a). The head of the academy at that time was Rabban Gamliel, whose behavior towards Rabbi Yehoshua was perceived by the students as lacking in respect. In response to this, the students deposed Rabban Gamliel and elected Rabbi Elazar ben Azarya to head the yeshiva in his place. The Gemara there relates that Rabbi Elazar ben Azarya opened the gates of the academy to all, removing the restrictions on acceptance instituted by Rabban Gamliel, and that all of the Sages engaged in a review of questions that had been left undecided at that time, reaching conclusions with regard to all of them.

The Ri”d suggests that the 72 elders mentioned by Shimon ben Azzai includes the 71 members of the Sanhedrin in Yavneh, as well as the muflah shel bet din – the elder who participated in the discussion without being a formal member of the group (see Masechet Horayot daf 4). Some suggest that the additional individual was Rabban Gamliel, who, according to the Gemara in Berakhot, did not take umbrage at the coup and participated fully in those discussions.

Zevachim 12a-b: Sacrifices that could not be brought

The Gemara presents two parallel cases –

- Ulla quotes Rabbi Yohanan as teaching: If someone accidentally commits a sin and sets aside an animal as a sin-offering, but before he brings it he becomes an apostate, the sacrifice cannot be brought even after he repents. Since there was a time that the sacrifice could not have been brought, it is disqualified.

- Rabbi Yirmiyahu quotes Rabbi Abahu who says in the name of Rabbi Yochanan: If someone accidentally eats cheilev (non-kosher fats) and sets aside an animal as a sin-offering, but before he brings it he loses his mind, the sacrifice cannot be brought even after he recovers. Again, since there was a time that the sacrifice could not have been brought, it is disqualified.

The Gemara explains that despite the similarities between them, Rabbi Yochanan needed to teach both of these laws. Had he only taught the first case we would have thought that the sacrifice could not be brought because the person disqualified it of his own volition, but perhaps the person who became insane should be treated like someone who was asleep. And had he only taught the second case we would have thought that the sacrifice could not be brought because his condition was beyond his control, but perhaps a situation where the person could always repent would be different.

The Gemara in Arachin (21a) explains that the owner of every sacrifice that is brought must be aware and willing to make that sacrifice. Thus, someone who is not in control of his faculties cannot bring a korban. With regard to the apostate, the Gemara in Chullin (5a) argues that it would be considered the sacrifice of an evil-doer, which is considered abhorrent before God (see Mishlei 21:27). The Gemara there discusses at some length whether this relates only to someone who transgresses one of the major sins (like idol worship, or desecration of the Sabbath), concluding that someone who is reputed to reject a single law will be allowed to bring sacrifices on all other transgressions, excluding the one that he is known to deny.

Zevachim 13a-b: During which activities will improper thoughts affect the sacrifice?

A recurring theme throughout the first perek of Masechet Zevachim has been that some sacrifices will become invalid if there are improper thoughts at the time that they are brought, while other sacrifices will remain valid korbanot, although they will not count towards their purpose and if their owner was obligated to bring that sacrifice, he will have to bring another.

During which activities will improper thoughts affect the sacrifice?

The Mishnah on today’s daf mentions four parts of the avodah – of the sacrificial service – where proper intent is essential –

- Shechita – slaughtering the animal (even though this need not be done by a kohen)

- Kabalat ha-dam – collecting the blood at the time of slaughter

- Holachah – carrying the blood to the altar

- Zerikat ha-dam – sprinkling the blood on the altar.

Rabbi Shimon argues that holachah – carrying the blood – should not be included in this list, since it is not an essential avodah. While the sacrifice cannot be brought without slaughtering the animal, collecting its blood or sprinkling its blood, if the sacrifice is slaughtered next to the altar, near the ulam, the hall leading to the Temple, then carrying the blood may not be necessary.

Following this discussion, we find in the Gemara that Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi testified that “in this aliyah – in this attic – I heard that a kohen who places his finger in the blood of a korban chatat – a sin-offering – will disqualify it [if he has an inappropriate thought at that moment].” This teaching is somewhat surprising, since the blood sprinkling of most sacrifices is directly from the basin holding the blood onto the altar, and the kohen never touches it. Sin offerings differ, since the kohen sprinkles it with his finger on the upper part of the altar (see, for example, Vayikra 4:6). Some suggest that we must view dipping fingers into the blood in the case of the sin-offering as the beginning of zerikat ha-dam, which is why proper intent is essential already at that point.

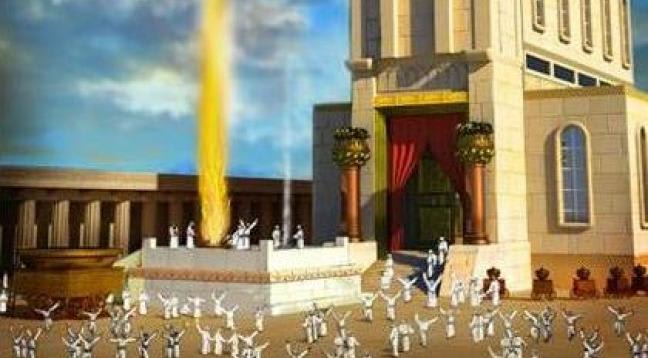

Zevachim 14a-b: A map of the Temple Mount

Different parts of the Temple courtyard area served different purposes. For example, kodshei kodashim – sacrifices of the highest level of holiness, including sin-offerings – were slaughtered on the side of the altar to the north (see Vayikra 1:11). What is unclear, however, is how the concept “to the north” is defined. In the continuation of Masechet Zevachim (daf, or page, 20a) we find a disagreement about this issue. One opinion is that it simply means anywhere to the north of the altar. Rabbi Elazar ben Rabbi Shimon adds the entire area to the west of the altar, which is called bein ha-ulam la-mizbe’ach – between the hall leading to the Temple and the altar – in the northern half of the courtyard. Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi includes the northern half of the courtyard on the east side of the altar, as well, up to the entrance to the courtyard.

This diagram illustrates the main areas of the Temple. It should be noted that the standard diagrams of the Temple Mount are situated so that the top is West, which, as can be seen, is where the Temple itself stood (when we stand at the Western Wall, we face east towards the Temple, which stood just to the east of the wall). In the middle we find the altar, together with the ramp that led up to it on its left (to the South). Just above it (to the West) is the area of bein ha-ulam la-mizbe’ach; to the right is the northern side of the Temple courtyard.

We learned on yesterday’s daf that according to Rabbi Shimon, holachah – carrying the blood – is not an essential avodah. The argument that he made was that the sacrifice cannot be brought without slaughtering the animal, collecting its blood or sprinkling its blood. Nevertheless if the sacrifice is slaughtered next to the altar, near the ulam (the hall leading to the Temple), then carrying the blood may not be necessary since the sprinkling can be done from there.

Reish Lakish points out on today’s daf that Rabbi Shimon would admit that in cases of sin-offerings that must have their blood sprinkled on the inner altar, holachah is an essential avodah. Since the animal cannot be slaughtered inside the Temple itself, the act of carrying the blood inside cannot be done in any other way.

Zevachim 15a-b: Who can perform the sacrificial service?

The second perek of Masechet Zevachim begins on today’s daf.

Where the first perek focused on a basic problem with sacrifices – the issue of a sacrifice that is brought with the wrong intent – the second perek deals with two other potential problems –

- when the person who is sacrificing the korban has the proper intent, but he is not fit to perform the sacrificial service, either because he is not a kohen or else he is a kohen who does not perform the service according to the accepted rules and regulations,

- when the problem is one of intent, but it is not connected with the intrinsic purpose of the sacrifice or with the identity of the owner. Rather the problem stems from intent to benefit from the sacrifice in the wrong time or in the wrong place. Although these are not mentioned specifically in the Torah, they are derived by the Sages from two sections of Sefer Vayikra – 7:16-18 and 19:5-8.

The first Mishnah teaches that if kabalat ha-dam – collection of the blood of the sacrifice – was done by someone other than the appointed priest (e.g. it was performed by someone who was not a kohen, or even by a kohen who was unfit for performing the sacrificial service for any one of a variety of reasons), the sacrifice would be invalid. Although the Mishnah specifically mentions that this law applies to a case where the kabalat ha-dam was done improperly, it appears that the law of this Mishnah would apply to any of the four basic avodot – sacrificial services:

- Shehitah – slaughtering the animal (this need not be done by a kohen)

- Kabalat ha-dam – collecting the blood at the time of slaughter

- Holakhah – carrying the blood to the altar

- Zerikat ha-dam – sprinkling the blood on the altar.

Kabalat ha-dam is mentioned by the Mishnah only because it is the first of the avodot that must be performed by a kohen.

In addition to his monumental translation and commentary on the Talmud, Rabbi Steinsaltz has authored dozens of books and hundreds of articles on a variety of topics, both Jewish and secular. For more information about Rabbi Steinsaltz’s groundbreaking work in Jewish education, visit www.steinsaltz.org or contact the Aleph Society at 212-840-1166.

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.