The Coming Week’s Daf Yomi by Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz

This essay is based upon the insights and chidushim (original ideas) of Talmudic scholar Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, as published in the Hebrew version of the Steinsaltz Edition of the Talmud.

Zevachim 44a-b: Gifts to the priestly family

In Sefer Bamidbar (18:9) the Torah lists a number of sanctified items that are given to the kohanim for their use. Aharon, the High Priest, is told:

“This shall be yours of the most holy things, reserved from the fire:

- Kol korbanam – every offering of theirs,

- Kol minchatam – every meal-offering of theirs,

- Kol chatatam – every sin-offering of theirs,

- Kol ashamam – every guilt-offering of theirs,

- Asher yashivu li – which they may render unto Me,

shall be most holy for you and for your sons.”

The Gemara on today’s daf offers an explanation of what is included in each of these cases, and particularly why the Torah needed to add the word kol – “every” – before each of them. According to the Gemara, within each category there are certain cases that we might have thought were not included as a gift to the kohanim, and therefore the Torah wants to emphasize that all of these belong to them.

The final clause – asher yashivu li – is understood by the Gemara to be teaching the law of gezel ha-ger; when the Torah granted money stolen from a convert to the kohanim, it is a gift that belongs entirely to the kohen, and he can even use it to give it to a woman for the purposes of marriage.

The case of gezel ha-ger is a unique situation. Ordinarily, if someone steals from another person and then takes a false oath denying the thievery, he must bring a guilt-offering and pay back the money that he stole plus an additional 20% penalty (see Vayikra 5:20-26). If the victim died, then the perpetrator would have to pay the money to the people who inherit him. In Sefer Bamidbar (5:7), the Torah teaches that if the victim had no one who would inherit him, then the money must be paid to the kohen. The Sages interpret this as referring to gezel ha-ger, since an ordinary Jewish person must have some surviving relative who would deserve to receive the payment.

Rashi points out that the word kol does not appear before asher yashivu li, indicating that there is no special law being taught, it is mentioned simply because it is in the list of those gifts given to the kohanim. Tosafot argue that there is a special halacha being taught here, based on the emphasis that it be given “for you and for your sons.” Their suggestion is that even though gezel ha-ger is not taken from the altar (“reserved from the fire”) nevertheless it becomes the property of the kohen who can use it for any purpose that he sees fit.

Zevachim 45a-b: Deciding laws for Messianic times

The Mishnah (43a) brings a disagreement between the Tanna Kamma and Rabbi Shimon with regard to a question about the application of pigul – inappropriate thoughts relating to time regarding a given sacrifice – to an animal that was to be brought on the inner altar but was being prepared in the outer courtyard. The Gemara on yesterday’s daf brings another opinion, that of Rabbi Elazar in the name of Rabbi Yossi HaGalili. The concluding sentence on yesterday’s daf was Rav Nachman quoting Rabbah bar Avuha in the name of Rav who said that the halacha follows this last opinion.

Reacting to this ruling, Rava asks hilkheta l’meshicha?! – are we establishing halakhic rulings for Messianic times, i.e. when the Temple will be rebuilt? Abayye responds to him by asking whether it would be appropriate to avoid learning any topics about the Temple service, since all of it should be considered hilkheta l’meshicha. Rather, Abayye argues, we study all aspects of Torah, even those that are not applicable since we are commanded – and rewarded – for Torah study. Therefore it is appropriate to learn the laws of the Temple service for that same reason. Rava replies that his question was why there is a need for a final ruling on these matters, since they are not practical at this time.

Tosafot point out that there are many places in the Gemara where a particular halakhic conclusion is reached regarding a question about the Temple service, but they argue that it is only in cases where the ruling will have practical ramifications as well. They also bring the opinion of Rabbenu Hayyim ha-Kohen who suggests that there is a particular problem with rulings regarding forbidden acts in the Temple, since there is no reason to rule about a forbidden act in Messianic times.

As a general principle, the study of any area of Torah in an attempt to understand the Torah’s true intent is a valuable exercise, whether the topic is practical or esoteric. Nevertheless, reaching a halakhic conclusion can be viewed as bowing to necessity, inasmuch as we need to decide how to act in a given case. Therefore there is no problem with studying the laws of pigul, the only surprise is to find that there are final rulings about those laws, since they are not applicable today.

Zevachim 46a-b: Proper intent when bringing a sacrifice

According to the Mishnah on today’s daf, a standard sacrifice needs to be brought with six things in mind:

- Zevach – The intent must be for the specific sacrifice that is being brought

- Zovei’ach – The intent must be for the owner of the sacrifice

- HaShem – The sacrifice must be brought with God in mind

- Ishim – The intent must be to sacrifice the animal on the altar

- Rei’ach – It must be brought in a manner that will raise the scent of the sacrifice

- Nichoach – The intention must be to fulfill God’s will.

In addition, a sin-offering or a guilt-offering must be brought with the specific transgression in mind.

Rabbi Yossi argues that even if someone did not have any of these ideas in mind, the sacrifice is fine, since this is a condition established by the Sages, that the intent that is necessary is that of the person who is performing the sacrificial service.

Rashi explains this last statement as meaning that the Sages insisted that the person who brings the sacrifice should not say aloud anything about his intentions, because if he makes a mistaken statement, his words may invalidate the sacrifice.

Rav Avraham Chaim Shor in his Tzon Kodashim explains that this refers specifically to the kohen who brings the sacrifice, and we fear lest the incorrect statement made by the kohen will invalidate the sacrifice being brought on behalf of another.

In his Commentary to the Mishnah, the Rambam offers an alternative approach to this Mishnah. He explains that the Tanna Kamma requires the owner of the sacrifice to have these six issues in mind, and Rabbi Yossi argues, saying that the condition established by the Sages is that we do not consider the thoughts of the owner at all; all that is important are the thoughts of the kohen who is performing the sacrificial service.

Zevachim 47a-b: Begin your day by reviewing this chapter

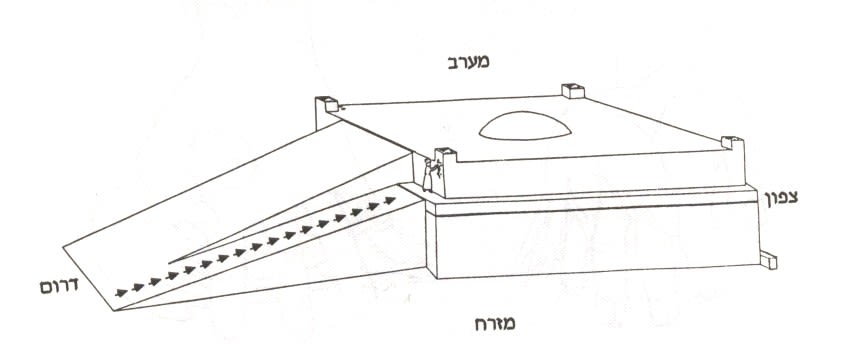

Perek Eizehu Mekoman, the fifth perek of Masechet Zevachim, begins on today’s daf. This perek offers an overview of all of the different sacrifices that were brought in the Temple, with the exception of korbanot ha-of – sacrifices brought from fowl – which are discussed in the following chapters, and menachot – meal offerings – that have their own tractates dedicated to those laws.

The sacrifices appear in this perek according to their levels of holiness. First we find the sacrifices that are kodshei kodashim – the holiest of holies – which are prepared in the northern part of the Temple courtyard; this is followed by kodashim kalim – ordinary holy sacrifices – which can be prepared anywhere in the courtyard. The next issue relates to the blood of the sacrifices, where and how they are sprinkled. The closeness of the sprinkling of the blood to the Holy of Holies in the Temple indicates the level of holiness of the sacrifice, and the Mishnah lists those that have a greater number of sprinklings first. Another detail that affects the level of holiness is the amount of time given for the korban to be eaten. The shorter the amount of time is, the holier the korban is. Each of the Mishnayot in the perek follow the same format – first where the sacrifice is slaughtered and prepared, where its blood is sprinkled, what is done with its meat and innards and finally where the remnants of the blood will be poured off.

The entire chapter of Perek Eizehu Mekoman has been inserted into the siddur as an introduction to the daily morning prayer service. The Beit Yosef quotes the Ra’ah in offering a number of reasons for this. First of all, it contains a review of virtually all of the sacrifices, and our prayers serve as replacements for the korbanot that can no longer be brought. Furthermore he points to the fact that we do not find any differences of opinion in the entire chapter, which can be understood as indicating that this is a chapter of oral tradition that has come down to us in the same language that it was received by Moshe on Mount Sinai.

Zevachim 48a-b: What the Sages enjoyed teaching

As we learned on yesterday’s daf, the fifth perek of Masechet Zevachim offers an overview of all of the different sacrifices that were brought in the Temple. The first sacrifices mentioned are the kodshei kodashim – the holiest of holies – that were brought in the northern part of the Temple courtyard, beginning with the Yom Kippur sacrifices.

The Gemara on today’s daf asks why the Mishnah begins with the Yom Kippur sacrifices, rather than the olah – the burnt-offering – which is where the law regarding the placement of the korban in the northern part of the Temple courtyard actually appears (see Vayikra 1:11). The Gemara answers that the Mishnah specifically chose to begin with korbanot that were derived by means of rabbinic inference rather than those that are clearly written in the Torah – keivan de’ati mi-derasha haviva lei – since the Sages are particularly fond of those halakhot that are established based on such logical means.

The idea that the Sages enjoyed their homiletical derivations and therefore place them first in the Mishnah appears a number of times in the Talmud. Ordinarily it refers to true Rabbinic derivations. In this case, however, the law that these other sacrifices are to be brought in the northern part of the Temple courtyard is a straightforward understanding of the passage in Sefer Vayikra (4:29) that says that they should be brought in the same place that the olah was to be brought. Nevertheless, the Sages still viewed the need for some level of search and examination of the biblical passages as more intriguing than a simple, straight-forward pasuk.

Tosafot explain that based on this argument one may have suggested that the olah sacrifice should appear last in the Mishnah, since it is the only korban where the northern placement is clearly stated. They explain that there are other considerations that come into play when establishing the order of the Mishnah; the olah is written immediately after the chatat – the sin-offering – since both have communal sacrifices in addition to personal sacrifices, as opposed to the asham – a guilt-offering – which is only brought as a personal sacrifice.

Zevachim 49a-b: How to derive biblical laws

As we have learned on yesterday’s daf, sacrifices that were kodshei kodashim – the holiest of holies – were brought in the northern part of the Temple courtyard. The source for this law appears in the Torah with reference to the korban olah – the burnt-offering – and the other sacrifices were derived from the olah.

The Gemara on today’s daf asks why the korban asham – the guilt-offering – needs to be compared to both the korban olah and the korban chatat – the sin-offering (see Vayikra 14:13 where the Torah requires that the asham be slaughtered in the same place as the chatat and the olah).

Ravina explains that if the Torah’s comparison connected the asham with the chatat, this may have led to a mistaken conclusion that a law derived by means of a hekesh (a word analogy) – like the law that the chatat must be slaughtered in the northern part of the Temple courtyard, which is derived from the clearly stated law regarding an olah – can then be used to teach that law in a similar situation – like using chatat as a source for the law for the korban asham.

In truth, in this particular case it is likely that we would have been able to derive the law of the asham from the law of the chatat, even though the chatat is not the original source of the law. This is because (as we learned on yesterday’s daf) the Torah clearly states that the chatat must be slaughtered in the same place that the asham was slaughtered, so it is not an ordinary hekesh, it is almost a biblical source. Nevertheless, because of the possibility that someone might mistakenly think that this law is derived from a hekesh and is used as a source for another halacha, we need to have a more solid, original source for the hekesh.

Zevachim 50a-b: Exegetical methods of deriving laws from the Torah

As we learned on yesterday’s daf, a law derived by means of a hekesh (a word analogy) – like the law that the chatat, the sin-offering, must be slaughtered in the northern part of the Temple courtyard, which is derived from the clearly stated law regarding an olah, the burnt-offering – cannot be used to teach that law by means of another hekesh – like using chatat as a source for the law for the korban asham, the guilt-offering.

The Gemara on today’s daf examines whether this rule is true in all cases where the source of the original law is not a clear biblical passage, but is learned by means of some exegetical derivation. For example, can something learned from a hekesh be used to teach based on:

- A gezeirah shava?

- A kal v’chomer?

- A binyan av?

All of these methods of analysis are among the middot she-haTorah nidreshet bahem – the exegetical principles established by the Sages and used to derive laws from the Torah. These specific examples are used as follows:

Hekesh – is an analogy. When two cases are mentioned together in the same passage or in adjacent passages, we can assume that since they are juxtaposed, they are analogous. For this reason, legal inferences may be drawn by comparing the two cases. On rare occasions, such as in our case, the analogy may be stated explicitly in the Torah.

Gezeira shava – is a verbal analogy. If the same word or phrase appears in two places in the Torah, we may infer on the basis of “verbal analogy” that the same law must apply in the other case, as well.

Kal vahomer – is an a fortiori inference. This is a rule of logical argumentation by means of which a comparison is drawn between two cases, one lenient and the other stringent. Kal vahomer asserts that if the law is stringent in a case where we are usually lenient, then it will certainly be stringent in a more serious case; likewise, if the law is lenient in a case where we are usually not lenient, then it will certainly be lenient in a less serious case.

Binyan av – is an interpretation based on induction. While there are different types of binyan avs, the simplest form of binyan av follows the logical pattern “just as we find in Case A that Law X applies, so too we may infer that in Case B, which is similar to Case A, law X should apply.”

In addition to his monumental translation and commentary on the Talmud, Rabbi Steinsaltz has authored dozens of books and hundreds of articles on a variety of topics, both Jewish and secular. For more information about Rabbi Steinsaltz’s groundbreaking work in Jewish education, visit www.steinsaltz.org or contact the Aleph Society at 212-840-1166.

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.