The Coming Week’s Daf Yomi by Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz

This essay is based upon the insights and chidushim (original ideas) of Talmudic scholar Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, as published in the Hebrew version of the Steinsaltz Edition of the Talmud.

Zevachim 114a-b: Sacrifices in the Land of Israel – I

The obligatory sacrifices described in Sefer Vayikra were brought in the Tabernacle in the desert, but their ultimate destiny was to be brought in the Temple in Israel. What was their status when the Children of Israel first entered the Land of Israel?

According to the Mishnah (daf 112) a person would not be held liable for bringing sacrifices outside of the precincts of the Temple, if they are brought before or after the appropriate time (e.g. torim – turtledoves – that had not yet reached adulthood, or bnei yonah – pigeons – that have become adults, see daf 68). Rabbi Shimon disagrees and rules that someone who brings a sacrifice whose time to be brought has yet to have occurred will be subject to malkot – lashes – for his transgression.

The Gemara on today’s daf searches for a source for Rabbi Shimon’s position, and Rabbi El’a quotes Reish Lakish as learning it from a passage in Sefer Devarim (12:8-9). According to this pasuk, the Torah forbids the people from bringing sacrifices the way they were brought in the desert. Rabbi Shimon’s interpretation of the command is that upon entering the Land of Israel, the Jewish people could no longer continue bringing communal sacrifices as they had done in the desert; only personal sacrifices consisting of nedarim and nedavot – voluntary sacrifices – could be brought in the Tabernacle when it was first erected in Israel (in Gilgal). This reading of the pasuk was understood to mean that this situation was to remain in force until the time that the people arrived at the menucha – “the resting place,” i.e. Shiloh – and the nachala – “the inheritance,” i.e. Jerusalem. Only then could obligatory sacrifices be brought as they were in the Tabernacle in the desert.

It was based on this that Rabbi Shimon reasoned that since it was forbidden to bring sacrifices in Gigal prior to the establishment of the mishkan in Shiloh, we learn the principle that mehusar zeman – a sacrifice whose time had not yet arrived – cannot be brought outside the Tabernacle. Similarly there is a prohibition in effect against bringing sacrifices outside the Temple when they could be brought at a later date.

Zevachim 115a-b: Who was to perform the sacrificial service – first-born or kohanim?

According to the Mishnah (112b) until the Tabernacle was established in the desert, sacrifices were brought on bamot – private altars – and the sacrificial service was performed by the bechorim, the first-born. After the Tabernacle was erected sacrifices could only be brought there and the sacrificial service was performed by the kohanim – descendants of Aharon HaKohen. According to the Mishnah, the commandment to sanctify the first born was given at the time of the Exodus from Egypt (see Sefer Shemot 13:2), and the first-born redeemed themselves from Temple service later on, as described in Sefer Bamidbar (3:12). According to the Talmud Yerushalmi, the reason for this was the participation of the first-born in sacrificing to the Golden Calf, something that the members of the Tribe of Levi did not do.

The Gemara on today’s daf quotes a baraita that offers an alternative approach to this question. According to Rabbi Assi, the first-born sacrificed for just one day, in conjunction with the experience of Mount Sinai. Thus, the “young men” who brought sacrifices (see Sefer Shemot 24:5) at that time did so for just that day, in the third month following the Exodus. From that time on until the Tabernacle was built – in the first month of the second year following the Exodus – Aharon’s son’s Nadav and Avihu served as priests. During the consecration ceremony of the Tabernacle, Nadav and Avihu died under tragic circumstances (see Vayikra, Chapter 10), and from that point on it was the rest of Aharon’s sons and their descendants who were responsible for the sacrificial service in the Temple.

Rashi has an alternative reading that seems to indicate that the “young men” in Sefer Shemot 24:5 did not actually bring the sacrifices, but represented the people as onlookers to the sacrificial service that was performed. According to this reading there is a possibility that the first-born never served a role in bringing sacrifices.

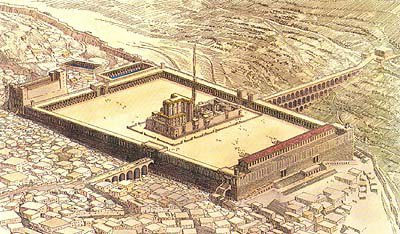

Zevachim 116a-b: Purchasing the Temple Mount

The place of the Temple on Mount Moriah is one of three places that the Tanach tells us was purchased and paid for in full. In Sefer Shmuel (II Chapter 24) we are told of a plague that struck the Jewish people as a result of King David’s decision to count the people. Gad the Prophet instructs King David to build an altar on the place of the granary of Aravnah the Jebusite, the hilltop that was destined to become the place of the Temple. Aravnah offers his granary, together with his cattle for sacrifices and the morigim and other utensils as firewood, but King David insists on purchasing these from him.

The Gemara quotes a baraita that points out an apparent contradiction between the price paid by King David according to the story in Sefer Shmuel (II 24:24-25) and the parallel story as related in Sefer Divrei HaYamim, or Chronicles (I 21:25-26). While in Sefer Shmuel we learn that King David paid 50 silver shekalim, in Sefer Divrei HaYamim the price is reported as 600 gold shekalim. The baraita explains that David collected 50 shekel from each of the twelve tribes so that each would have a share in the 600 shekel price.

The Gemara relates that when Rava was learning this with his son they dealt with a further question – the difference between the silver shekalim in Sefer Shmuel and the gold shekalim in Sefer Divrei HaYamim. The explanation offered by Rava is that David collected silver shekalim from each tribe that added up to the value of 50 gold shekalim, so that the sum total collected was the value of 600 gold shekalim.

In a side comment, Ulla explains that the morigim that Aravnah wanted to donate were boards that were used to thresh the grain. In the time of the Mishna these implements were still in use – as they still are today – albeit in a more developed form that allowed the animal driver to sit while the wheels of the morigim threshed the grain.

Zevachim 117a-b: Sacrifices in the Land of Israel – II

We have already learned the opinion of Rabbi Shimon, who ruled that upon entering the Land of Israel and erecting the Tabernacle temporarily in Gilgal, the people could not bring obligatory sacrifices until the Tabernacle was established in Shiloh in a more permanent manner (see above, daf, or page 114). This position was disputed by other Sages, as we learn on today’s daf.

The Chachamim rule that all sacrifices that were brought in the desert were brought on the altar in Gilgal as well, and in both places individual sacrifices were limited to a korban olah (a burnt-offering) or a korban shelamim (a peace-offering). Rabbi Yehuda rules that all sacrifices that were brought in the desert were brought on the altar in Gilgal – including all public sacrifices as well as private sacrifices. The difference between the two periods was that upon arriving in Israel, even when the mishkan was operating in Gilgal, people were allowed to build bamot – private altars. The sacrifices brought on these private altars, however, were limited only to a korban olah or a korban shelamim. Rabbi Meir believes that any private sacrifice that was a neder or a nedava – voluntary sacrifices – could be brought on a private altar, e.g. the sacrifices brought by someone who voluntarily accepted nezirut upon himself.

There is one case where all agree that a public, obligatory sacrifice was brought on the altar in Gilgal. According to the story in Sefer Yehoshua (Chapter 5), the Children of Israel crossed the Jordan River just prior to Passover and they brought the korban Pesach in Gilgal almost immediately upon their arrival. The uniqueness of the korban Pesach lies in the fact that although it is obligatory on every individual, it is viewed as a communal sacrifice, since everyone is required to bring it at the same time and it is eaten in groups rather than by individuals.

Zevachim 118a-b: Where did God’s presence rest?

Following the description of the places where public altars were established during biblical times that appeared in the Mishnah (112b), Rav Dimi quotes Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi as teaching that there were three places where the Shechina – the Holy Spirit of God – rested on the Jewish people, in Shiloh, in Nov and Givon, and in the permanent Temple in Jerusalem.

Four places are mentioned in Rav Dimi’s teaching, and, in fact, the Ein Yaakov‘s version of the Gemara is that there were four places where the Shechina rested on the Jewish people. Nevertheless, Rashi explains that Nov and Givon are viewed as a single period when private altars were permitted, separating between the two periods of Shiloh and the Temple when private altars were forbidden.

The Maharsha grapples with the fact that there were other places where the Tabernacle stood – in the desert for 39 years and in Gilgal for an additional 14 years while the land was being conquered and divided between the tribes. He explains that outside the Land of Israel was not seen as a place where the Shechina truly rested. During the 14 years of capturing and dividing the land, the aron – the Holy Ark – did not permanently rest in the Tabernacle, so that was not counted, either. Based on the passage in Sefer Yirmiyahu (7:12), it was only after the establishment of the Tabernacle in a semi-permanent place in Shiloh that the Shechina was seen as “coming to rest” among the people.

The city of Shiloh, which was located in the Tribe of Ephraim (see Sefer Shoftim, or Judges 21:19) is about 22 miles north of Jerusalem on the ancient mountain ridge road that traversed the country from north to south, just under ten miles south of Shechem.

In the modern town of Shiloh today the remains of the Tabernacle have been found, and a modern synagogue has been built commemorating it.

Zevachim 119a-b: Ramifications of a lost Ark

As we have learned, there were periods during biblical times when sacrifices were limited to a specific place (i.e. in the Tabernacle in the desert, when the Tabernacle was established in Shiloh and when the permanent Temple was built), but there were times when sacrifices could be brought on private altars, as well, like when the Tabernacle was standing in Nov and Givon.

The city of Nov became the resting place of the mishkan after Shiloh was destroyed at the time of Eli HaKohen’s death (see Sefer Shmuel I, Chapter 4 and Sefer Yirmiyahu 7:12). Nov was destroyed by King Shaul at about the time of Shmuel’s death (see Sefer Shmuel I, 22:19), at which time the mishkan was taken to Givon (see Sefer Divrei HaYamim, or Chronicles I 16:39).

While the Tabernacle was standing in Nov and Givon, the aron – the Holy Ark – was not in the mishkan. Rather, after it had been captured in battle by the Plishtim, upon being returned seven months later it was placed in Kiryat Ye’arim (see Sefer Shmuel I, Chapters 6-7), where it stood until being taken to Jerusalem by King David (see Sefer Shmuel II, Chapter 6).

The fact that the aron did not reside in the mishkan had halakhic ramifications. As Rabbi Yohanan explains to Resh Lakish on today’s daf, without the aron in its place, ma’aser sheni – the second tithe – which was usually eaten by its owner within the walls of the city of Shiloh or of Jerusalem, was not eaten.

This ruling of Rabbi Yochanan is subject to different interpretations. According to Rabbeinu Chananel, during this period, the obligation of ma’aser sheni was simply suspended. Without the aron, there could be no fulfillment of eating the tithe lifnei Hashem – “before God” (see Devarim 12:18) – so this tithe was not taken, even as the other tithes remained obligatory. Others suggest that once the obligation to separate ma’aser sheni was established with the erection of the Tabernacle in Shiloh it could not be suspended, rather it had to be redeemed and exchanged for money. Finally, according to Rashi the ma’aser sheni had to be separated, but it could be eaten anywhere.

Zevachim 120a-b: Contrasts between private altars and the great public altar

During the time periods when a bamat yachid – a private altar – was permitted (see above daf 112) even as the Tabernacle was operating, how were sacrifices brought? Were the rules and regulations associated with sacrifice the same in private settings as they were in the bamah gedolah – the great altar – in Gilgal, Nov or Givon? This is the question on which today’s daf – the closing page in Masechet Zevachim – chooses to focus.

Some laws are clear. For example, the Gemara quotes a baraita that teaches that the time limitations regarding sacrifices that must be eaten on the day of sacrifice or, at most, on the day following sacrifice, apply to a bamat yachid just as they apply to the bamah gedolah. This law is derived from the passage in Sefer Vayikra (7:11) that equates the laws of all sacrifices to each other.

There are also clear differences between a bamat yachid and the bamah gedolah. A different baraita offers a list that points out physical differences between these altars. The bamah gedolah requires horns on the corners, a ramp leading up to it, a base or foundation and that the altar be square – all of which were required based on passages in the Torah that specifically required these things in the Tabernacle or lifnei Hashem – “before God.” These elements were not required in private altars.

The main difference of opinion lies in the sacrificial service itself. The Gemara relates that Rabbi Yochanan required that a korban olah – a burnt offering – have its skin removed – to be given to the owner of the sacrifice, much as the skin of an olah is given to the kohanim when such a sacrifice is brought on the bamah gedolah – and the innards removed to be burned on the altar. Rav disagrees, ruling that there is no need to skin the olah and remove its innards; the entire animal was to be burnt on the altar.

The Gemara explains that this difference of opinion is based on a disagreement about how to understand the teaching of Rabbi Yossi HaGalili who taught that originally in the desert a korban olah was burned in its entirety, a situation that changed only when the Tabernacle was established. Rav understood that this law applied only on the altar associated with the Tabernacle; Rabbi Yochanan understood that from the time of the Tabernacle forward the law has changed.

In addition to his monumental translation and commentary on the Talmud, Rabbi Steinsaltz has authored dozens of books and hundreds of articles on a variety of topics, both Jewish and secular. For more information about Rabbi Steinsaltz’s groundbreaking work in Jewish education, visit www.steinsaltz.org or contact the Aleph Society at 212-840-1166.

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.