The Coming Week’s Daf Yomi by Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz

This essay is based upon the insights and chidushim (original ideas) of Talmudic scholar Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, as published in the Hebrew version of the Steinsaltz Edition of the Talmud.

This month’s Steinsaltz Daf Yomi is sponsored by: Dr. and Mrs. Alan Harris, The Lewy Family Foundation, and Marilyn and Edward Kaplan

Yoma 65

In the Mishnah at the beginning of the perek (62a) we are introduced to Rabbi Yehuda’s opinion from which the Gemara on our daf concludes that the two se’irim – the goat chosen by lottery to be sacrificed and the one whose lot is to be sent to its death in the desert – are interconnected. As such, if the blood of the sacrifice is spilled before it has been sprinkled on the altar, obligating the sacrificial goat to be replaced, the scapegoat needs to be replaced, as well. Similarly, if the scapegoat dies before the blood of the sacrifice has been sprinkled, we will need to replace both se’irim.

The question of a sacrifice that can no longer be brought because of an outside issue, leads the Gemara to introduce another case where Rabbi Yehuda offers an opinion, which seems to contradict his position in our Mishnah.

The Mishnah in Masechet Shekalim (2:1) teaches that there was no obligation for every individual to bring half-shekel coins to the Beit ha-Mikdash, rather they could be collected in every community, exchanged for larger coins and sent with a messenger to Jerusalem.

What if the money was lost or stolen en route to the Temple? The Mishnah teaches that responsibility for lost or stolen money depends on when the money disappeared.

In order for the communal sacrifices that were brought in the Temple to be considered to have come from the entire nation, even before the half-shekel donations arrived in the Mikdash, money was set aside on Rosh Chodesh Nissan for the purchase of sacrifices. This money – called Terumat ha-lishka – was, in essence, a loan that was to be repaid when the half-shekalim arrived. Our Mishnah teaches that if Terumat ha-lishka had already been set aside, the money in the hands of the messenger was considered to have already reached the treasurer of the Temple. In such a case, the messenger swears to the Temple treasurer that he did not handle the money in an irresponsible fashion. If, however, Terumat ha-lishka had not yet been set aside, then the money still belonged to the townspeople when it was stolen. In such a case, the messenger must swear to them that he did not handle the money in an irresponsible fashion, and each of them will have to send another half-shekel to the Mikdash.

What if the original money was found or returned by the robbers?

Rabbi Yehuda rules that it can be considered to be the townspeople’s payment for the next year. Rava explains that Rabbi Yehuda believes that the money can be held over, since obligatory sacrifices of this year can be brought next year, as well.

Abayye points out that were this true, Rabbi Yehuda should recommend holding the se’ir that could not be sacrificed this year for use next year.

The Gemara concludes by quoting a passage (Bamidbar 28:14) that teaches that a sacrifice must be new every year. The shekalim, which are used also for other purposes aside from sacrifices, can be switched to another year according to Rabbi Yehuda.

Yoma 66

A series of questions on our daf are directed at Rabbi Eliezer, who appears to make a serious attempt to avoid answering them directly.

When asked whether the scapegoat could be carried if it became sick, Rabbi Eliezer answered “the scapegoat can carry both me and you.” When asked whether a replacement for the person who escorted the scapegoat to the cliff could be inserted if the first person became ill, he answered “both you and I should remain in peace.”

When asked whether the person who escorts the scapegoat should go down and kill it in the event that it did not die in the fall off the cliff, he answered by quoting a passage in Sefer Shoftim (Judges) (5:31) “So should all of God’s enemies be destroyed.”

Perhaps the simplest way of understanding Rabbi Eliezer’s answers is that he was suggesting that these situations would never occur, and therefore there was no need to discuss them in a serious way.

Many of the commentaries argue that Rabbi Eliezer was not avoiding the questions, rather he chose to express his opinion on them in an indirect manner. His answer that the scapegoat could carry the people hinted that such carrying would be permissible on Shabbat. Saying that they should remain in peace indicated that anyone could step in and be a fitting substitute for the designated person who became ill. Finally, quoting the passage in Sefer Shoftim showed that he felt that once the commandment was fulfilled and the scapegoat was thrown from the cliff, no further involvement was necessary. In fact, the Jerusalem Talmud reports that the scapegoat occasionally escaped into the desert.

The Gemara recounts several other questions that were presented to Rabbi Eliezer, about which he gives unclear responses, and explains that he was not simply trying to avoid the questions, rather he was abiding by his personal position of never offering a ruling that he did not have a tradition on from his teachers (see Sukkah 27b, where Rabbi Eliezer explains this position). Nevertheless it should be noted that this holds true only for questions of a final legal ruling. With regard to the arguments and discussions that took place in the bet midrash, he certainly played an active role that included his own original suggestions.

Yoma 67

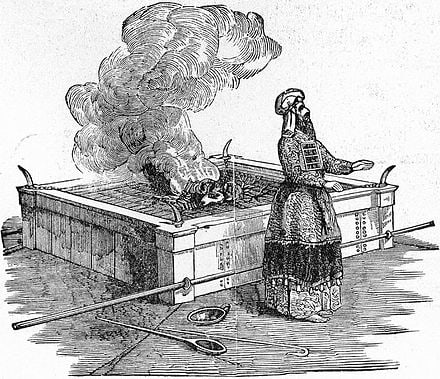

The focus of the sixth perek of Masechet Yoma has been the se’ir ha-mishtale’ach – the scapegoat – which is not sacrificed in the Temple like a regular korban, but is taken to the desert where it metaphorically takes the sins of the Jewish people with it to its death. This process, which is a central part of the Yom Kippur service, is not explained by the Torah.

The Gemara on our daf lists the se’ir ha-mishtale’ach together with a number of other ritual acts that are perceived as being ones about which the evil inclination and the non-Jews of the world point to as indicative of the lack of logic in Jewish law. The baraita opens with a passage in Vayikra 18:4 that obligates the Jewish people to perform both mishpatim and chukim. The baraita interprets mishpatim as logical commandments, ones that man would establish even if there was no Biblical command to keep them, e.g. idol worship, sexual depravity, murder and stealing. Chukim, on the other hand, are commandments that do not seem to have a logical basis, like our case of the scapegoat, eating pork, wearing or making use of forbidden mixtures, or the process of readmitting a recovered leper into the community.

Some point to certain similarities in all of these cases, in that they either are things that are forbidden even as something points to their permissibility (pigs have split hooves – one of the signs of a kosher animal; sha’atnez, the mixture of wool and linen is made up of two permissible items) or involve permissibility stemming from something forbidden (the leper being readmitted to the community or the scapegoat erasing the sins of the community). It is clear that all of these cases appear to be some kind of magic and do not fall into the normal categories of halakhah, which leads to the possibility of their being questioned.

Aside from the abovementioned cases, variant readings of the Gemara include other examples of halakhot that appear to be similarly strange, which may be added to the list of things about which non-Jews or the evil inclination ridicule the Jews. They include eglah arufa (the calf that is beheaded as part of the ritual when a dead body is found between two cities), removal of the hair as part of the process of the nazir who completes his nezirut, and the prohibition against mixing meat and milk.

Yoma 68

The seventh perek of Masechet Yoma, which begins on today’s daf, opens with a description of the kohen gadol reading the command of the Yom Kippur service as it appears in the Torah (Vayikra 16:1-34; 23:26-32). The Jerusalem Talmud derives the need for this public reading from the passage “…and he did as God commanded Moshe,” which is understood to obligate not only performance of the avodah, but also teaching about it.

The Mishnah notes that the people who came to watch the Yom Kippur service needed to choose whether to attend the Torah reading or to go to see the burning of the sacrifices (the par and se’ir), which were done outside of Jerusalem, as was taught in the previous perek. According to the Rambam in his commentary to the Mishnah, the Mishnah emphasizes this in order to teach that the rule forbidding someone to pass up the opportunity to perform one mitzvah in order to do another (ein ma’avirin al ha-mitzvot) only applies to someone who is actually obligated in a mitzvah, and not to someone who is simply observing the mitzvah, even taking into consideration the idea that be-rov am hadrat melekh – that the King is honored before a large group.

The Torah reading described here only takes place after the se’ir ha-mishtale’ach – the scapegoat – has arrived at its destination in the desert, which is why the last Mishnah in the sixth perek informs us that the kohen gadol waited for the signal that the mitzvah of the se’ir had been accomplished. Three opinions are offered by the Mishnah as to how the message was sent to the Temple. According to the Tanna Kamma, people were assigned to stand along the route to the desert. When the designated person completed his mission he would wave a flag, which would signal the next person along the line to do so, and each person would take up the signal until it reached the mikdash. Rabbi Yehuda argues that we know the distance to the desert is three Roman miles, so we merely need to measure out the time that it takes to walk that distance and we know that the mitzvah has been done. Rabbi Yishmael suggests that we would know it because the scarlet ribbon that was tied around the horns of the se’ir had a parallel ribbon tied in the Temple. When they turned white (based on the passage in Yeshayahu 1:18) it would be clear that the scapegoat had reached its final destination. It appears that Rabbi Yehuda felt that we did not need conclusive proof, so the Tanna Kamma’s suggestion of using flags was unwieldy and unnecessary. The Tanna Kamma, however, accepts neither Rabbi Yehuda’s estimate, nor Rabbi Yishmael’s reliance on miracles.

Yoma 69

Today’s daf includes one of the most famous stories in the Gemara, when the kohen gadol, Shimon ha-Tzaddik met Alexander Mokdon. The story is taken from Megilat Ta’anit (which appears in the Steinsaltz Talmud after Masechet Ta’anit), where the baraita explains why during the second Temple period the 25th day of Tevet was celebrated as a minor holiday, which was called “the day of Mount Gerizim.”

Our Gemara introduces it in the context of the halakha that the kohen gadol was not permitted to wear the special bigdei kehunah – the clothing worn by a priest – outside the Temple. Yet, in the following story we find that Shimon ha-Tzaddik did so.

Megilat Ta’anit records how the Samaritans approached Alexander Mokdon and requested permission from him to be permitted to destroy the Temple in Jerusalem. Alexander agreed. When word of this got to Jerusalem, the kohen gadol, Shimon ha-Tzaddik dressed in his priestly garments and headed north together with an entourage to greet Alexander. Upon reaching Antipatris, the city that was considered the northern border of the second Temple period Judea, which stood apparently in the vicinity of today’s Rosh ha-Ayin, the two groups met. Upon seeing the High Priest, Alexander stepped down from his chariot and bowed before Shimon ha-Tzaddik. In response to the objections of his followers, Alexander explained that in every battle he sees a vision of the High Priest leading him to victory. Shimon ha-Tzaddik appealed to Alexander to save the Temple, explaining that prayers on his behalf were recited there on a regular basis. Alexander acceded to the request and permitted the Jews to destroy the Samaritan Temple instead.

The Gemara offers two explanations to Shimon ha-Tzaddik’s behavior in wearing bigdei kehunah to this meeting. One is that they were not true bigdei kehunah, they were replicas that were similar to the priestly garments. The other explanation is that this was a case where an exception was made, since the fate of the Temple and the Jewish people was at stake (the passage from Tehillim 119:126 is invoked as a source for that idea).

It should be noted that other sources support the veracity of this story, as it appears in Josephus with minor variations.

Yoma 70

The first Mishnah in the perek (68b) teaches that the kohen gadol read the Torah publicly before the people who came to the Temple to see the avodat Yom Kippur. It further itemizes the eight blessings that the High Priest recited over this reading. They include a blessing on:

- Torah

- Avodah (Temple service)

- Modim (a blessing of thanksgiving)

- a request for forgiveness

- the Temple itself

- the Jewish People

- the kohanim (that their sacrifices should be accepted)

- Shomei’a Tefillah (that the prayers should be accepted).

Although these are the blessings enumerated in the Mishnah, there are a wide variety of opinions about the actual blessings recited and their number. For example, the Me’iri suggests that there really were ten blessings recited, since the normal blessings made before and after Torah reading should not be counted, since they are not unique to the avodah of Yom Kippur. He adds a blessing about the city of Jerusalem.

Most of the blessings that are unique to the Temple service no longer appear in our liturgy. Nevertheless there are some exceptions. For example, Rashi says that the blessing on the avodah is similar to the retzei blessing that is said in the daily amidah, with a different closing blessing. Rather than using the contemporary prayer for the return of God’s presence to the Temple (which would obviously have been inappropriate when the Temple was standing and in use) the blessing concluded she-otkhah levadkhah be-yirah na’avod – that only You should we serve in awe. According to some traditions, this blessing is retained on the occasions when the kohanim bless the congregation on holidays during the Mussaf prayers.

Some suggest that the blessing recited over the Temple was to the effect of “It should be Your will that You should establish your Temple forever, and be desirous of it and allow Your holy presence to reside in it forever, blessed be You God, who dwells in the Temple.”

Yoma 71

The Mishnah on our daf teaches about the bigdei kehunah – the special clothing worn by the kohanim and the kohen gadol. The kohen gadol wears eight special garments, of which four of them were the standard attire of a regular kohen. The bigdei kehunah included:

Kohen:

- Choshen (breast plate)

- Ephod,

- Me’il (robe)

- Tzitz (head plate).

With regard to the mitznefet we find a disagreement among the commentaries. According to the Rambam, both the regular kohen and the kohen gadol wore the same type of head covering, which was made of a long strip of fabric 16 amot long. The difference between them was in the way in which it was wrapped, with the kohen making it into a tall turban and the kohen gadol would wrap it around his head and beard. The Ra’avad understands that only the kohen gadol wore a mitznefet, while the regular kohanim wore tall, thin hats.

The Gemara derives from passages in Shemot 39 that the basic material used in the fabric for the bigdei kehunah was linen, derived from flax – Linum usitatissimum. It is an erect annual plant growing between 30 and 100 cm tall, with slender stems. The flowers are pure pale blue, 1.5-2.5 cm diameter, with five petals. The fruit is a round, dry capsule from which oils are derived. Flax is one of the oldest cultivated crops on record; its growth is mentioned in ancient Egypt. Today it is cultivated mainly in tropical areas. The main product of flax is the fibers from which linen is made. Flax fiber is extracted from the bast or skin of the stem of flax plant. Flax fiber is soft, lustrous and flexible. It is stronger than cotton fiber but less elastic. It is removed via a lengthy process whereby the plant is dried out and then soaked until almost rotten. At that point they are once again dried out and the fibers combed out.

In addition to his monumental translation and commentary on the Talmud, Rabbi Steinsaltz has authored dozens of books and hundreds of articles on a variety of topics, both Jewish and secular. For more information about Rabbi Steinsaltz’s groundbreaking work in Jewish education, visit www.steinsaltz.org or contact the Aleph Society at 212-840-1166.

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.