The Coming Week’s Daf Yomi by Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz

This essay is based upon the insights and chidushim (original ideas) of Talmudic scholar Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, as published in the Hebrew version of the Steinsaltz Edition of the Talmud.

This month’s Steinsaltz Daf Yomi is sponsored by Dr. and Mrs. Alan Harris, The Lewy Family Foundation, and Marilyn and Edward Kaplan

Yoma 58a-b

The Mishnah on our daf describes how the kohen gadol, having completed the zerikat ha-dam – the sprinkling of the blood – on the parokhet of the Holy of Holies, now turns his attention to the zerikat ha-dam that he is obligated to do on the golden altar in the heikhal (see Vayikra 16:18). As the Torah commands, the kohen gadol takes the blood of the par (bull) and of the se’ir (goat), mixes them together, and places blood from the mixture on each of the four karnot ha-mizbe’ah (“horns” of the altar).

According to the Tanna Kamma, the kohen gadol walks around the altar, sprinkling blood on each corner. Rabbi Eliezer disagrees, arguing that the kohen gadol stood in one spot and simply reached over the altar, sprinkling blood as necessary. To understand Rabbi Eliezer’s position, it is important to remember that the mizbe’ach ha-zahav – the golden altar – was only two cubits tall and one cubit in length and width (see diagram), which allowed him to easily reach over it.

Once the kohen gadol completed the sprinkling of the blood on the corners of the mizbe’ach, the Mishnah teaches that he sprinkled blood on the altar itself (see Vayikra 16:19) before pouring the remainder of the blood down a drain that was built into the foundation of the altar itself. This blood mixed in the plumbing pipes of the Temple with the remainder of other blood that had been poured into a similar drain in the outer altar. From there they emptied into the Kidron Valley, where their remains were sold as fertilizer. From this topographical map, which includes, in its center, the Second Temple-era platform on which the mikdash stood, it is clear that the Kidron valley, running to the east of the Temple Mount, is the natural run-off point for sewage from the Temple. The walls of the Temple Mount actually stand at the very edge of the banks of the dry river, in which the Shiloach spring flows.

Yoma 59a-b

The Mishnah on the previous daf taught that the remnants of the blood from the sacrifices were poured down a drain on the altar, from where they emptied into the Kidron and were sold as fertilizer. Our Gemara quotes a baraita that teaches a difference of opinion between the sages with regard to the status of this blood – specifically, whether the rules of me’ilah would apply to it. Rabbi Meir and Rabbi Shimon believe that me’ilah applies, while the Chachamim argue that it does not.

Me’ilah is, in essence, stealing or deriving benefit from something owned by the Temple. Once something is consecrated to the Temple, it is forbidden for someone to derive benefit from it. The laws of me’ilah are briefly mentioned in the Torah (see Vayikra 5:14-16), but the many detailed precepts associated with it are discussed at length in Masechet Me’ilah in the Talmud. The rules and regulations surrounding me’ilah are more stringent than those in the rest of the Torah in that someone who derives such benefit will be held liable for it even if it was done accidentally, or even against his will. Similarly, someone who sends an agent to use something that belongs to the Temple will be considered to have been mo’el, even though in the rest of the Torah we rule that ein shali’ah le-devar aveirah – a person cannot be considered to have sent someone else to perform a sinful act, but rather, everyone is responsible for their own actions.

In Masechet Me’ilah we learn that there are different rules and regulations regarding various sacrifices and objects donated to the Temple and that the holiness attached to a given object will, on occasion, be removed.

The discussion in our case revolves around the status of the blood from a sacrifice and whether the laws of me’ilah apply to it. The Gemara asserts that the aforementioned disagreement between the tanna’im is only on a Rabbinic level, but on a Biblical level all are in agreement that there is no me’ilah in our case. Several sources are given for the fact that the Torah does not forbid use of the blood, but the conclusion of the Gemara is that once the mitzvah is completed, the rule of me’ilah can no longer apply.

Yoma 60a-b

We learned on the previous daf that use of an object belonging to the Temple whose mitzvah has already been fulfilled can no longer be considered me’ilah (deriving benefit from an object consecrated to the Temple). The Gemara points out that there are a number of other things that belong to the Temple which retain their status even after the mitzvah has been completed. They include:

- Terumat ha-deshen – the ashes that are removed from the altar at the beginning of the morning Temple service, and

- Bigdei kehunah – the clothing worn on Yom Kippur by the kohen gadol, who removes them after he completes the avodah.

The Gemara explains that these cannot be used as a source to teach us that me’ilah applies even after the mitzvah is fulfilled, because of the rule that shenei ketuvim ha-ba’im ke-ahad ein melamdin (two passages that come to teach a single idea cannot be used as a source to be

applied elsewhere).

Generally speaking, the Talmud derives general principles from a passage written in one place and applies them in other places where they logically apply, unless there are specific indications in the pasuk that limit its applicability. In a case like ours, where the Torah specifically teaches the same rule in two places, it is a clear indication that we do not have a general principle, but rather a rule that applies specifically in these two places and nowhere else. There are occasions when the Gemara can prove that the cases are so different from one another (or that each one has a unique quality about it) that we would not be able to extrapolate from one to the other. In such a case, the Gemara would suggest that we can, in fact, apply the rule more generally, even though it is taught by the Torah in both cases.

The Gemara does point out that there is an opinion which allows applying a rule generally even if it does appear in the Torah in two places. According to this opinion, the fact that the rule is repeated twice simply indicates that the Torah wants to emphasize the general applicability of that rule. Even that opinion, though, recognizes that if a rule is repeated three times, then it is limited in its scope and cannot be applied to other cases in the Torah.

Yoma 61a-b

The Mishnah (60a) teaches that the various activities that make up the Yom Kippur service must be done in the order described. If done out of its proper order, then lo asah klum – it is as though nothing was done. What happens, then, if the blood for haza’ah (sprinkling) spills before the act is performed? Two opinions are brought. The Tanna Kamma rules that a new animal must be slaughtered and the entire process of the avodah started over, since the slaughtering is supposed to take place at the beginning. Rabbi Elazar and Rabbi Shimon argue, claiming that the blood from the newly slaughtered animal can be used immediately, since the haza’at ha-dam is a separate mitzvah.

The Gemara on our daf discusses whether this rule is true regarding other processes that took place in the Temple. Take, for example, the case of a metzorah who has been examined by the kohen who declares that he is no longer leprous. The Torah teaches (see Vayikra 14:1-32) that a recovered metzorah has to undergo a series of activities both outside (shaving off all body hair) and inside the Temple (handing the kohen the lamb to bring as a korban asham together with the log of oil). Once the sacrifice is brought, the kohen takes from the blood and places it on the metzorah‘s earlobe, thumb and big toe. The kohen then takes the oil, first sprinkling it on the altar and then placing some on the metzorah‘s earlobe, thumb and big toe, with the remainder of the oil being poured on his head. Finally, a korban chatat and a korban olah are brought.

What if the oil spills after the sprinkling but before it is placed by the kohen on the body of the metzorah? Does the same argument that we found in our Mishnah with regard to the order of the Yom Kippur service apply here?

Rabbi Yehuda ha-Nasi quotes Rabbi Yaakov on this matter. At first it appears that Rabbi Yaakov distinguishes between the two cases, but the Gemara quotes a baraita based upon which the Gemara concludes that Rabbi Yaakov taught that the same rule applies to metzorah, as well.

Rabbi Yaakov ben Kurshai lived in the generation prior to the canonization of the Mishnah, and, as Rabbi Yehuda ha-Nassi’s teacher, played an important role in its development. Some claim that he was Elisha ben Avuya‘s grandson.

Yoma 62a-b

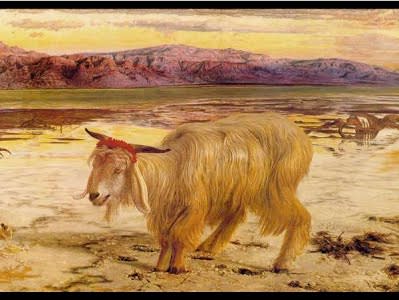

The sixth perek of Masechet Yoma, which begins on our daf, focuses on the se’ir ha-mishtale’ach – the scapegoat – which is a central part of the Yom Kippur service (see Vayikra 16:20-22). As we learn in the Mishnah, in the beginning two goats are chosen; one will be offered as a sacrifice on the altar, while the other will be sent to the desert as the scapegoat. The two goats are supposed to be identical in their height, their appearance and their value, and should be purchased together.

The Tosafot Yeshanim point to a Gemara in Sanhedrin, which says that no two individuals are truly identical, and ask how two identical goats can possibly be found. The answer they suggest is that we must distinguish between people who have clearly identifiable characteristics and animals whose appearance may be much more similar. Nevertheless, they refer to a comment in the Jerusalem Talmud that seems to indicate that no two things will ever be identical – even two grains of wheat have differences between them. This leads the Tosafot Yeshanim to conclude that the Mishnah merely means that the two animals should be as similar as possible in their general appearance.

With regard to value, according to the Jerusalem Talmud, we are not concerned about their actual selling price, but rather about their true value. Even if they were purchased for different amounts of money, as long as they are of equal value we have met the requirement; if their values were significantly different, even if they cost the same amount of money (e.g. one of the sellers gave a discount to the Temple representative) the requirement would not be met.

Finally, the Mishnah recommends that they be purchased at the same time, and the commentaries explain that ideally they should even be purchased from the same merchant, as we try to limit anything that distinguishes the two animals from one another.

Yoma 63a-b

Once the se’ir ha-mishtale’ach – the scapegoat – is chosen by means of the lottery, its status as a sacrifice is unclear. On the one hand, it is still an integral part of the Yom Kippur Temple service. On the other hand, it is not a korban la-Shem – a sacrifice to God – as it is to be sent to Azazel. Do the regular rules and regulations that apply to other korbanot

apply here, or not?

The Gemara on our daf examines pesukim and comes to conclusions that seem to distinguish between different laws.

With regard to a mum – a blemish that would disqualify an animal from being brought as a sacrifice – the Gemara quotes a baraita that derives from psukim that the rules of blemishes apply to the scapegoat, even though it will not be brought as a sacrifice. Yet, relating back to a baraita that was taught on a previous page, our Gemara points to the ruling that if the se’ir ha-mishtale’ach was slaughtered outside of the Temple precincts, the person who killed it would not be held liable for performing shechitat kodashim ba-hutz – slaughtering a consecrated animal outside the mikdash – since this animal is not destined to be brought as a sacrifice in the Temple.

This ruling is applied by the Gemara to other types of consecrated animals, as well. If they have been donated to the Temple but are not to be sacrificed, they, too, will not be held to the laws of korbanot. Specifically, kodashei bedek ha-bayit – property of the Temple that is used for its upkeep and beautification – fall into this category. These things, which are donated to the Temple for purposes other than sacrifice, are subject to the laws of me’ilah (see daf 59), but not the laws of sacrifices. There is a specific law forbidding the donation of an animal that could be brought as a korban to the Temple as kodashei bedek ha-bayit. An animal that is free of blemishes that could be sacrificed can only be consecrated to the Temple for that purpose.

Yoma 64a-b

The Torah teaches that it is forbidden to kill an animal and its son on one day (oto ve’et b’no lo tishhatu b’yom ehad – see Vayikra 22:28). This is understood by the sages as forbidding the slaughter of a mother and its child together (some understand that it refers to the father, as well, if his identity is known).

In a case where the se’ir ha-mishtale’ah – the scapegoat – has already been chosen and an emergency situation comes up (e.g. meat is needed for someone who is deathly ill, which would allow its preparation even on Yom Kippur) for which its mother is slaughtered, would the se’ir ha-mishtale’ach still be sent off to be killed, or does the rule of oto ve’et b’no lo

tishhatu b’yom ehad still apply? (The Ritva points out that the question would apply even if the mother was slaughtered in a forbidden situation on Yom Kippur, but the Gemara preferred to offer a case where it would, theoretically, be permissible.)

The Gemara suggests that this is not a problem at all, since the language of the pasuk clearly states that what is forbidden is shechita – ritual slaughter. Thus, the halakha is that if the mother animal is killed in some other fashion, it would be permissible to slaughter the child. Since the se’ir ha-mishtale’ach is to be killed by being thrown off a cliff in the desert, it would appear that the rule of oto ve’et b’no lo tishchatu b’yom echad should not apply.

In response, the Gemara quotes a teaching from Ma’arava (literally: “the West” i.e. the Land of Israel, which is to the west of Babylon, where this discussion took place) that being thrown from the cliff is considered shechita in the case of the se’ir ha-mishtale’ach.

In essence, the question debated on our daf is how narrowly we should define shechita. Tosafot suggest that this Gemara is teaching us that it should be defined broadly, to mean that it was killed for its ritual purpose. In the case of the se’ir ha-mishtale’ach, that is accomplished by means other than traditional slaughter.

In addition to his monumental translation and commentary on the Talmud, Rabbi Steinsaltz has authored dozens of books and hundreds of articles on a variety of topics, both Jewish and secular. For more information about Rabbi Steinsaltz’s groundbreaking work in Jewish education, visit www.steinsaltz.org or contact the Aleph Society at 212-840-1166.

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.