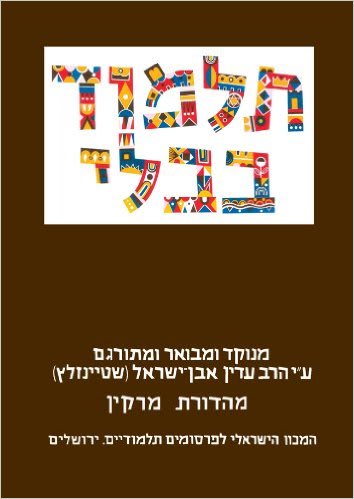

The Coming Week’s Daf Yomi by Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz

This essay is based upon the insights and chidushim (original ideas) of Talmudic scholar Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, as published in the Hebrew version of the Steinsaltz Edition of the Talmud.

This month’s Steinsaltz Daf Yomi is sponsored by Dr. and Mrs. Alan Harris, The Lewy Family Foundation, and Marilyn and Edward Kaplan

Sotah 34a-b

As we have learned, the seventh perek of Masechet Sotah discusses how some religious ceremonies need to be said in Hebrew, while others can be said in any language. A series of segues leads the discussion from the blessings and curses that the Children of Israel recited on Har Gerizim and Har Eival to a general discussion about entering the land of Israel at the end of the forty year trek through the desert, and the story of the spies who entered the land to scout it out many years before.

Our Gemara focuses on some of what the spies chose to speak about when they returned to report to the Jewish People. According to the Torah (Bamidbar 13:22), they told of a number of giants who lived in the area of Hebron, mentioning that Hebron was built prior to the city of Zo’an in Egypt. This is understood by the Gemara as teaching that although Hebron was poor agricultural land, it was considered better than Zo’an, which was the best land in Egypt.

The term used to describe the land around Hebron is trashim, which describes ground that is so hard that it cannot be plowed and planted normally. Generally speaking, such earth is found in rocky areas where the earth between the rocks also becomes hard and cannot be used for normal agricultural uses. The Gemara’s proof that the land in Hebron was trashim is that it was used as a burial place.

The Sefat Emet questions how the fact that the burial place of the forefathers of the Jewish people is in Hebron can serve as a proof that the land was of poor quality. He explains that according to burial custom in Israel, soft earth was not a good place to bury people, since the walls of the grave will collapse. Rather, the ideal burial ground is one where the earth is hard and cannot be used for farming. In such a place, the body will remain properly buried.

Sotah 35a-b

As we saw on yesterday’s daf, our Gemara is focusing on the story of the spies (see Bamidbar 13–14). The Torah teaches that after the spies offered their testimony about the land, a report that was rejected by God and Moshe, the spies died of plague (see Bamidbar 14:37). Resh Lakish understands the passage as saying that they died an unusual death.

What was this unusual death?

According to Rabbi Chanina bar Papa, their tongues became elongated reaching their navels and worms came out of their tongues, penetrating their navels and out of their navels, penetrating their tongues. The Iyun Yaakov explains this strange description as stemming from the fact that they sinned against the land of Israel – referred to as the center, or navel, of the world (see Yechezkel 38:12) – by use of their tongues.

Rav Nachman bar Yitzhak suggests that they died of askara. The Gemara’s askara is identified as diphtheria, which is a very contagious and potentially life-threatening infection that usually attacks the throat. A membrane that forms over the throat and tonsils make it hard to swallow. The infection also causes the lymph glands and tissue on both sides of the neck to swell to an unusually large size. Until the advent of modern medicines, it was particularly lethal; children literally choked to death. During Second Temple times, one of the responsibilities of the “Anshei Ma’amad” – the people whose week was consecrated for spiritual duties – was to fast “so that children would not be struck by diphtheria.”

According to the Talmud, askara comes to the world because people do not tithe properly, or, according to Rabbi Elazar b’Rabbi Yosi, because people spread evil tidings (Lashon ha-ra). Given the identification of the spies’ sin as lashon ha-ra regarding the land of Israel, we can easily understand why the unusual death that they suffered may be assumed to be this disease.

Sotah 36a-b

Our Gemara is continuing the ongoing discussion of the Children of Israel entering the land of Israel after their trek through the desert. One of the topics discussed on today’s daf is the passage that the tzirah will be sent before the people in order to drive out the Canaanite nations (see Shemot 23:28). The Targumim (translations of the Bible) and most of the commentaries translate tzirah as a type of flying insect, likely the Vespa orientalis – the Oriental hornet. This insect has a painful sting, which is particularly potent if it stings a sensitive part of the body. An attack by a group of these hornets can bring about a person’s death. The ibn Ezra suggests that the word tzirah refers to a type of disease (like tzara’at) but our Gemara does not appear to support such an approach.

The Gemara attempts to understand how to reconcile a baraita that says that the tzirah did not actually enter the land of Israel with the passage quoted above that seems to indicate that they did.

Reish Lakish suggests that the tzirah stopped at the banks of the Jordan River, shooting their venom across onto the Canaanites, blinding their eyes above and castrating them below (based on Amos 2:9).

Rav Papa suggests that there were two separate groups of tzirah – one connected to Moshe, which only accompanied the Jewish people until the Jordan River, and another connected to Yehoshua, which entered the land. Although there is no real source for the idea that there was a separate group of tzirah accompanying Yehoshua, the Iyun Yaakov suggests that the promise made to Yehoshua that all of the miracles that were done for Moshe would be done for him, as well, can be understood as a source for the hornets assisting him, as well.

Sotah 37a-b

There is a well-known midrash that describes how when the Children of Israel stood poised by the Red Sea with the Egyptian army chasing them, the first person to jump in, thereby precipitating the splitting of the sea, was Nachshon ben Aminadav from the tribe of Yehudah. According to our Gemara, there is a difference of opinion as to whether this is what happened.

According to Rabbi Meir, the argument that took place on the shore of the Red Sea related to the fact that members of all of the different tribes wanted to be the first to jump into the water, and it was the tribe of Binyamin that succeeded in reaching the waters first. Rabbi Meir teaches that this act is what allowed the tribe of Binyamin to merit that the Temple was built within the boundaries of their shevet.

Rabbi Yehuda disputes this version of events, claiming that when the tribes were standing on the shore of the Red Sea, none of them wanted to throw themselves into the water until Nachshon ben Aminadav from the tribe of Yehuda did so. At that time Moshe was in the midst of prayer and God instructed him to pay attention to his people who were already in the water, and instruct the others to follow. Rabbi Yehuda teaches that the act of Nachshon ben Aminadav was what allowed the tribe of Yehuda to merit the monarchy.

In the book Ben Yehoyadah, Rabbi Yosef Chaim mi-Baghdad’s work on the aggadic portions of the Talmud, the author points out that the reward granted to both Yehuda and Binyamin are eternal rewards – the Jewish people’s monarchy will always be from the house of King David, and the place of the Temple will always remain on Har Ha-Bayit in Jerusalem. The Iyun Yaakov argues that both rewards contain an element of monarchy, since King Shaul, the first king of Israel, came from Shevet Binyamin.

Sotah 38a-b

The Mishnah (37b-38a) focuses on birkat kohanim – the three part blessing that the kohanim give to the rest of the people – distinguishing between the way it was done in the Temple and the way it is done outside the Temple as part of the prayer service. Among the differences enumerated in the Mishnah are the way God’s name is pronounced (according to the actual writing or the way it is commonly said) and the way the kohanim hold their hands during the blessing (in front of them or above their heads).

The Gemara presents an odd situation and asks how birkat kohanim should be done when the entire group is made up of kohanim. Rav Ada quotes Rav Samlai as teaching that they stand up and make the blessing in the normal way. In response to the question of who they are then blessing, Rabbi Zeira says that the blessing will affect those Jews who are working in the fields. When another baraita is quoted that appears to require some listeners to remain in the synagogue and recommends that some of the kohanim rise to give the blessing and others remain to listen and respond appropriately, the Gemara distinguishes between a situation when there are ten people in total, all of whom are kohanim and when we will have a quorum of people remaining to receive the blessing when some of their friends stand to offer the blessing.

The Talmud Yerushalmi takes up a similar question and concludes that the women and children in the synagogue will be the ones who respond to the blessing, although, as noted, our Gemara does not seem to think that there is any significance to a response, unless it is made by a standard minyan (a quorum of ten) adult males.

Sotah 39a-b

Our Gemara quotes a series of halakhot taught by Rabbi Zeira in the name of Rav Chisda. Several of them focus on how the public Torah reading must be done. He teaches, for example, that –

- The congregation cannot respond “Amen” until the reader has finished his blessing

- The reader cannot begin the reading until after the congregation has finished their response of “Amen”

- The metargem cannot begin his translation until the reader has completed the passage

- The reader cannot continue the Torah reading until the metargem has finished his translation.

The job of the meturgaman was to partner with the ba’al korei (reader) who was reading the Torah and translate that reading – one pasuk at a time – into a language that could be understood by all. That language was the standard one spoken by people at that time – Aramaic. The Targum that was used in the synagogue was Targum Onkelos, the same one that appears in standard Chumashim. Many of the rishonim insisted on keeping the tradition of the meturgaman alive even after the language was no longer understood by the masses.

Although we are not familiar with the practice today, the meturgaman was an essential fixture in the synagogue during Torah reading in the time of the Mishnah and the Talmud, as well as for generations that followed. For Jews of Yemenite extraction, the meturgaman is part of the standard Torah readings in their synagogues to this day, and in some communities the Yemenites also added an Arabic translation that was penned by Rav Saadiah Gaon.

There is another type of meturgaman who is occasionally referred to in the Gemara; he is the individual whose job it was to “broadcast” the teachings of the Sage to the audience who came to hear him – an essential job prior to the invention of the loudspeaker. Such a meturgaman not only presented the words of the Sage, but offered explanations and clarifications of the teachings, as well.

Sotah 40a-b

Among the statements that the Mishnah (32a) says must be made in Hebrew are the blessings of the kohen gadol. The Mishnah on our daf discusses these blessings that are made by the kohen gadol on Yom Kippur. After the kohen gadol finishes the special Temple service of the day, the chazan ha-knesset ceremoniously hands a sefer Torah to the rosh ha-knesset, who hands it to the segan (assistant) kohen gadol, who gives to it the kohen gadol. The kohen gadol then reads selections from the Torah and makes eight brachot.

The Tosafot ha-Rosh points out that there is no clear source that these blessings must be made in Hebrew any more than other brachot. He suggests that the sanctity of the day may be what encouraged the sages to establish that the service be done specifically in Hebrew.

In his commentary to the Mishnah, the Rambam explains that the procedure of handing the Torah from one person to another is an attempt to honor the Temple and the proceedings by making it a ceremony that involves many people.

The rosh ha-knesset was in charge of the ongoing activities of the bet ha-Knesset. In many communities this job was given to the individual who was the head of the community. In some synagogues we find a special seat reserved for the Rosh ha-Knesset. During the Second Temple period there was a special synagogue that was situated on the Temple Mount where the people who came to the bet ha-mikdash would assemble for set prayers. It was in that synagogue that the sifrei Torah were kept.

The chazan ha-knesset was more of a functionary – a Shamash – who was responsible to make sure that things were kept in proper order. In some synagogues the chazan ha-knesset also served as the teacher of young pupils, or was responsible for their learning. Since they occasionally also led the services, the term became used popularly to describe the individual who leads the services on a regular basis.

In addition to his monumental translation and commentary on the Talmud, Rabbi Steinsaltz has authored dozens of books and hundreds of articles on a variety of topics, both Jewish and secular. For more information about Rabbi Steinsaltz’s groundbreaking work in Jewish education, visit www.steinsaltz.org or contact the Aleph Society at 212-840-1166.

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.