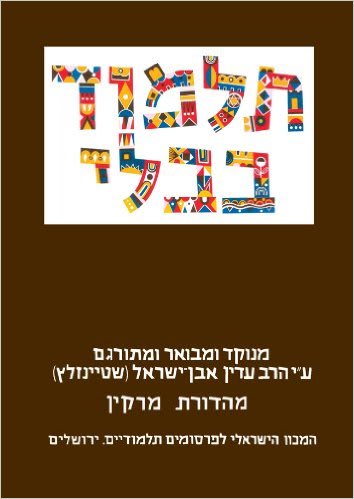

The Coming Week’s Daf Yomi by Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz

This essay is based upon the insights and chidushim (original ideas) of Talmudic scholar Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, as published in the Hebrew version of the Steinsaltz Edition of the Talmud.

Introduction to Masechet Makkot

Masechet Makkot is a companion tractate to Masechet Sanhedrin, and effectively completes it, inasmuch as it also deals with criminal law and the punishments meted out by the Jewish courts. This stands in contrast to the earlier tractates of Seder Nezikin whose focus was on civil law and personal interactions. At the same time, Masechet Makkot differs from Masechet Sanhedrin in that Sanhedrin deals mainly with serious crimes that deserve capital punishment, while Makkot discusses other types of crimes whose punishments are less severe.

Aside from capital punishment, there are three types of punishments meted out by the Jewish courts. They are:

- Monetary payments

- Exile

- Lashes

Jewish law does not recognize imprisonment as a punishment, although there are circumstances when a suspect is held so that he will not escape (see, for example, Vayikra 24:12, Bamidbar 15:34).

There are three general topics that are discussed mainly in Masechet Makkot, even though they appear in other places in the Talmud, as well. These are the laws of eidim zomemim (false witnesses), galut (exile) and malkot (lashes). While there is no clear connection between these topics, they are included here as a completion of the laws of bet din that were taught in Masechet Sanhedrin.

The source for eidim zomemim appears in the Torah (Devarim 19:16-21). The main idea is that if witnesses offer testimony against someone that will potentially lead to punishment – a death sentence, lashes or a monetary payment – if another set of witnesses come and claim that the first set could not possibly have seen this incident because they were with them in another place at the time of the crime, the first group will receive whatever punishment would have been given to the accused. This ruling is considered to be a hiddush – a new, unusual concept taught by the Torah – since other types of contradiction, e.g. witnesses who say that they saw the incident and it happened otherwise, would not lead to this ruling. When there is simply contradiction – two witnesses say that one thing occurred and two witnesses say that they saw something else take place – the court throws out both testimonies, since we do not know which group to believe.

The concept of galut – exile – is also a unique ruling. According to the Torah (see Bamidbar 35:24-29 and Devarim 19:2-7), a person is sent from his home to one of the six arei miklat – cities of refuge – in the event that he killed his fellow accidentally. It appears that exile accomplishes three things –

- It serves as a punishment

- It offers some level of atonement

- It protects the killer from the go’el ha-dam – the relative who acts as a “blood redeemer” to avenge the death.

The combination of these three purposes makes clear that not every accidental death will lead to the exile of the perpetrator. On occasion, the accident may be something that should have been prevented, and exile will not be an appropriate punishment, nor is it severe enough to offer atonement. Sometimes the accident may be something that could not possibly have been prevented, and there will be no need for punishment or atonement.

Malkot, or lashes, are also clearly mandated in the Torah (see Devarim 25:1-4), although the Torah does not specify what the rasha – the evildoer – who deserves malkot may have done to deserve this punishment. The oral tradition of the Sages on this matter is clear – someone who transgresses one of the negative commandments of the Torah is liable to receive lashes. The application of malkot accomplishes three things: punishment, atonement and deterrence. The punishment is severe enough that there is a requirement to examine the person who will be receiving the punishment to ensure that it will not cause permanent damage. Deterrence stems from the fact that aside from the physical pain, the lashes are given publicly in order to embarrass the perpetrator.

In point of fact, this punishment was not given very often, since there are many negative commandments that do not fall into the category of malkot. Furthermore, just as we find with regard to capital punishment, the court does not mete out this punishment unless they are certain beyond any doubt that he performed this crime purposefully and with malice aforethought. Thus we need not only two witnesses to the crime, but we must also know that the perpetrator was warned that the act was forbidden and that he would be punished for doing it.

While Masechet Makkot focuses on these matters, as in every tractate, other topics are discussed, as well. The tractate includes collections of aggadic material, most of which offer another perspective on these topics – on the reward for the performance of the commandments and how sometimes even things that appear to be negative may hint to the ultimate good in the World to Come.

In addition to his monumental translation and commentary on the Talmud, Rabbi Steinsaltz has authored dozens of books and hundreds of articles on a variety of topics, both Jewish and secular. For more information about Rabbi Steinsaltz’s groundbreaking work in Jewish education, visit www.steinsaltz.org or contact the Aleph Society at 212-840-1166.

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.