The Coming Week’s Daf Yomi by Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz

This essay is based upon the insights and chidushim (original ideas) of Talmudic scholar Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, as published in the Hebrew version of the Steinsaltz Edition of the Talmud.

Horayot 8a-b: What is equivalent to all of the Torah?

Aside from the passages that we have been discussing in Masechet Horayot that appear in Sefer Vayikra (chapter 4) that teach the laws of sacrifices for a High Priest, the High Court or the king whose error in judgment leads to accidental transgressions, there is another set of passages in Sefer Bamidbar (15:27-29) that also teach of a unique sacrifice that is brought in such a case. The Gemara on today’s daf explains that the passages in Sefer Bamidbar refer to a specific case – when avodah zarah, idol worship, was performed because of an error in judgment.

How is it evident from these passages that they refer to avodah zarah, which is not mentioned explicitly there?

A number of explanations are suggested by the Gemara.

In the bet midrash of Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi it was taught that we derive this because of the references to these mitzvot as being spoken to Moshe by God, and also commanded by God to the Jewish People by means of Moshe. Which mitzvah is unique in that it was spoken by God and commanded to the Jewish People by Moshe? The suggestion is that this refers to the first two of the Ten Commandments, which are spoken in the first person. These two commandments teach the laws of avodah zarah.

Rava teaches that when the Torah says that it is referring to someone who errs and transgresses et kol ha-mitzvot ha-eleh – all of the mitzvot – we must search for a mitzvah that is representative of all the mitzvot. He argues that avodah zarah is the mitzvah that is representative of all the mitzvot.

Although we find other examples of Rabbinic teachings that suggest that a given mitzvah is equivalent to the entire spectrum of mitzvot, nevertheless the commandments regarding belief in God are viewed as truly basic to all of the mitzvot.

Rashi explains Rava’s teaching as being based on the Rabbinic teaching that anyone who accepts avodah zarah, by definition rejects the entire Torah. The Me’iri suggests that once someone accepts a foreign god, it is clear that the mitzvot have no importance of meaning to him, so it is as if he rejects them all.

Horayot 9a-b – When to bring a sin-offering

It is a serious misunderstanding to think that in the time that the Temple stood people could bring sacrifices to atone for sins that they committed. In fact under most circumstances, sacrifices could be brought for atonement only for certain sins and only when the sin was done accidentally.

This point is emphasized in the Mishnah on today’s daf that teaches that sin-offerings are brought –

- A sheep or a female goat by an individual sinner (Vayikra 4:27-28, 31)

- A male goat by the nasi – the king (Vayikra 4:22-23)

- A bull by the bet din – the High Court or by the moshiach – the High Priest

only if they were sins for which the punishment is zedono karet ve-shigegato chatat – for doing them with malice aforethought would have been karet (literally “being cut off”) – a heavenly punishment, and if done by accident would have obligated the perpetrator in a sin-offering.

This last clause, that an accidental perpetrator would be obligated to bring a sin-offering, appears to be redundant, since that is precisely what we are trying to determine. Tosafot explain that it is simply a common phrase to say zedono karet ve-shigegato chatat, but that the point is that it must be something for which a person would receive karet, if done on purpose. In fact, the Rosh points out, this expression acts as a reminder that almost all cases where the punishment is karet, the atonement for doing the act accidentally is a hatat – a sin-offering.

The first Mishnah in Masechet Keritot enumerates 36 forbidden acts for which a person would receive the punishment of karet when done on purpose. If any of these are done accidentally, the person who does them must bring a chatat with the exception of five –

- Someone who does not perform a brit milah (circumcision)

- Someone who does not bring a korban peach (Passover sacrifice)

- A megadef – someone who blasphemes

- A tamei – someone who is ritually impure who eats of kodshim (sacred food)

- A tamei who enters the precincts of the Temple

Of these five, no sacrifice is brought for the first three since the person did not perform a punishable act. The last three do not bring an ordinary sin-offering, but a different sacrifice, instead (see Vayikra 5:1-13).

Horayot 10a-b – Jewish kings as public servants and a sighting of Halley’s Comet

In Sefer Melakhim, or Kings (II 15:5) the navi describes how King Azariah was struck with leprosy that did not allow him to continue acting in his capacity as monarch, so his son, Yotam, acted in his stead. During this period Azariah was exiled to bet ha-chofshit – literally “the house of freedom” – which is understood by the Gemara to indicate that the Jewish monarch is supposed to see his role as that of a servant to the people. The Me’iri argues that the simple meaning of the phrase was that the king had a retreat where he could rest from the stresses of his work, and that Azaria retired to that place when he became unable to fulfill his duties as king, but that the Sages made use of the terminology to teach a lesson about Jewish leadership.

To underscore this teaching, the Gemara tells a story that ultimately leads to the appointment of two scholars – Rabbi Elazar ben Chisma and Rabbi Yochanan ben Gudgeda – to positions of responsibility with the admonition that they were not being honored, rather they were being asked to accept a position of servitude.

The story that leads to this goes as follows:

Once Rabbi Yehoshua and Rabban Gamliel were traveling on a boat. Rabban Gamliel took bread; Rabbi Yehoshua took bread as well as flour. The trip took longer than expected, and Rabbi Yehoshua shared his food – which he baked using the additional flour that he had brought – with Rabban Gamliel. Rabban Gamliel asked Rabbi Yehoshua how he knew that the trip would take longer than expected, and Rabbi Yehoshua explained that he knew of a certain star that appears every 70 years that fools the navigators, and that he thought that it might create problems with the trip. Impressed with his knowledge, Rabban Gamaliel asked Rabbi Yehoshua why he was traveling on the boat. The Rosh, quoting the Ramah, explained that he asked why someone with this knowledge would have risked traveling at this time. In response, Rabbi Yehoshua pointed to Rabbi Elazar ben Chisma and Rabbi Yochanan ben Gudgeda as examples of people who are very intelligent but cannot succeed in supporting themselves. This made Rabban Gamliel decide to give them positions of responsibility.

The star referred to by Rabbi Yehoshua was a comet, whose orbit brought it back to Earth at regular intervals. Perhaps the most famous comet is Halley’s Comet whose orbit brings it to Earth every 76 years, and it is possible that Rabbi Yehoshua was referring to it. If so, this may be the earliest recorded reference to it in history.

Horayot 11a-b – The Messiah: The Anointed one

The word moshiach is invariably connected with Messianism and the end of days, but its actual meaning is “the anointed one” – that is, the one who has been anointed with anointing oil. In our context the term ha-kohen ha- moshiach (Vayikra 4:2) refers to the anointed priest who errs and sins. The Mishnah teaches that this excludes a High Priest who is merubeh begadim – who serves with the additional vestments of the kohen gadol, but who has not been anointed, which was the case throughout most of the Second Temple period.

What was this shemen ha-mishcha, this anointing oil?

The Torah teaches that a unique anointing oil must be prepared to consecrate the mishkan – the Tabernacle – and its vessels (see Sefer Shemot 30:22-33) as well as the High Priest, Aharon ha-kohen and his children. Our Gemara teaches that the kings of Israel were also anointed, although there was no need to anoint a king who replaced his father in peaceful succession.

The Gemara quotes a baraita where Rabbi Yehuda teaches that the oil was produced by boiling the roots of the plants from which it was made. Rabbi Yossi objects that such a method could not possibly have produced enough oil to perform the necessary tasks, rather the roots were placed in water where they were boiled, and when the oil was extracted from the roots it would float on the water where it could be removed. Rabbi Yehudah responded that there were many miracles in the production and use of the oil. Although only 12 lugin were produced, it sufficed to anoint all of the vessels in the mishkan as well as Aharon and his sons throughout the week of dedication of the Tabernacle. Furthermore, based on the passage in Sefer Shemot (30:31), the oil remained for use at the end of days.

One of the ingredients in making this oil, tzori, may be identified as the plant Commiphora apobalsamum, from which balsam oil is taken. The highest quality perfume drips from the plants, but most of the perfume is extracted by means of boiling its branches. When such oil was used for medicinal purposes, its main use was for incense and fragrant oil. During the time of the Mishnah it was literally worth its weight in gold.

In the late 20th century, such oil was found in a cave near the Dead Sea.

Horayot 12a-b: More on anointing oil

Although we learned on yesterday’s daf that the anointing oil made by Moshe at the time of the consecration of the mishkan was supposed to remain for use at the end of days, nevertheless, the Gemara on today’s daf teaches that it was already missing by the end of the first Temple period.

According to a baraita quoted by the Gemara, the aron – the Ark of the Covenant – had been hidden away towards the end of the first Temple period by King Yoshiyahu, who understood that the passage (Devarim 28:36) which described the exile was referring to his time. The Radak, in fact, explains that this is the passage that was highlighted in the sefer Torah discovered during Yoshiyahu’s reign (see the story in II Melakhim 22). According to that tradition, several other items that were on display in the Temple were concealed together with the ark. They included the container of manna, Aharon the High Priest’s staff and the shemen ha-mishcha, the pitcher of oil used for anointing. Rabbi Elazar explains that by use of a series of gezeirot shavot – parallel word usage in the Torah – King Yoshiyahu understood that these things which were kept next to the aron in the Holy of Holies were supposed to remain together, and when faced with the threat of exile and desecration, he chose to hide them all.

As we learned, the shemen ha-mishcha was used to anoint kings and high priests. The Rosh points out that the need to anoint the high priest is a clear passage in the Torah (see Shemot 30:30), but there is a prohibition to use the oil on any other person (see Shemot 30:32), whose punishment is karet (see above, daf 9). How was the decision made to use this oil on kings, as well?

He answers that the Gemara in Megilla understands that it is only forbidden to use this oil on a normal person. The king is not simply an adam and therefore he does not fall into the category of the prohibition.

Horayot 13a-b: Sages named “Others” and “Some Say”

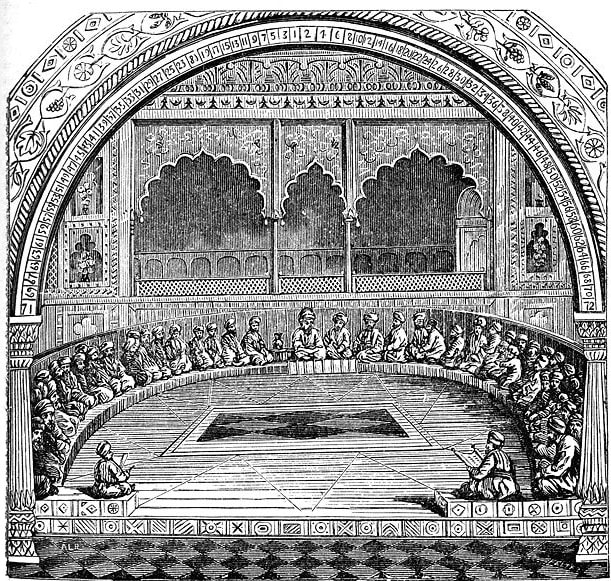

The Gemara on today’s daf describes the honor that was given to the various leaders and teachers. According to the baraita:

When the nasi – the head of the Sanhedrin – entered, all would stand and remain in that position until he told them to sit.

When the av bet din (who was second in importance) entered, two rows would stand up on either side of him, and would remain standing until he reached his seat.

When the chacham (the third in importance) entered, the students would stand up when he passed by and immediately return to their seats.

Rabbi Yochanan explains that this was established during Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel’s term in office, when he was the nasi, Rabbi Meir was the chacham and Rabbi Natan was the av bet din. Originally the students stood up before all, but Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel was disturbed that the position of nasi was not given special recognition, so he instituted the above practice on a day that neither Rabbi Meir nor Rabbi Natan was there. When they learned of the change in procedure, they conspired to rectify matters.

The Gemara relates that Rabbi Meir suggested to Rabbi Natan that they ask Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel to teach Masechet Uktzin – a small set of Mishnayot at the end of Seder Taharot that does not have Talmudic discussions on it in either the Jerusalem or Babylonian Talmud. Since he is unfamiliar with it – after the destruction of the Temple, the study of ritual purity lagged and even a scholar like Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel was not expert in it – we will step forward and proclaim that he is unworthy to be nasi, and we will move up in our positions.

One of the students, Rabbi Yaakov ben Korshai, heard this discussion and was concerned lest it lead to the public humiliation of the nasi, so he sat down behind Rabbi Shimon and reviewed the material aloud. Hearing laws of purity with which he was unfamiliar, Rabbi Shimon committed them to memory and successfully taught them when challenged to do so by Rabbi Meir and Rabbi Natan. Recognizing the attempt at mutiny, Rabbi Shimon then commanded that they be removed from the bet midrash.

Ultimately it became clear that the students turned to Rabbi Meir and Rabbi Natan for advice and direction even while they were exiled from the bet midrash, so Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel consented to allow them to return, but as punishment they lost the right to have their teachings ascribed to them. Rabbi Me’ir’s teachings were to be recorded as the words of acherim “others,” while Rabbi Natan’s teachings were recorded as yesh omrim “some say.”

The Bet Shmuel explains Rabbi Meir’s epithet as indicating that he started the plan and others followed his suggestion. In his Meromei Sadeh the Netziv points out that it carries with it an oblique reference to the fact that Rabbi Meir was a student of the disgraced tanna, Elisha ben Avuya, who was called Acher.

Ben Yehoyada argues that Rabbi Meir and Rabbi Natan were not planning to undermine Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel’s position on a permanent basis, rather they wanted him to recognize the embarrassment of changing the norms and protocols of honor in the bet midrash.

Horayot 14a-b: Mount Sinai or an uprooter of mountains?

On yesterday’s daf we learned of the differences of opinion between Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel on the one hand and Rabbi Meir and Rabbi Natan on the other hand. The Bet Shmuel explains that the following discussion in the Gemara offers some background to their disagreement.

Rabbi Yochanan taught: On the following point there is a difference of opinion between Rabbi Shimon ben Gamliel and the Sages. One view is that “Sinai” – a well-read scholar – is superior to an “oker harim,” literally “one who uproots mountains,” i.e. a sharp dialectician and the other view is that the sharp dialectician is superior. Rav Yosef was a well-read scholar; Rabbah was a sharp dialectician. A question was sent up to the scholars in Israel: Who of these should take precedence? They sent them word in reply: ‘A well-read scholar is to take precedence’; for the Master said, ‘All are dependent on the owner of the wheat’.

The Gemara continues and says that Rav Yosef, nevertheless, did not accept office so Rabbah headed the yeshiva for twenty-two years and only after this period did Rav Yosef take up the office. Out of respect for Rabbah, Rav Yosef did not allow the doctor to visit him at home during this period.

According to the Bet Shmuel, Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel was a sharp dialectician but did not have great erudition, which is why Rabbi Meir and Rabbi Natan’s attempted coup was based on the assumption that he would not be able to teach Masechet Uktzin. Rabban Shimon clearly believed that his analytical abilities made him the appropriate choice to head the Sanhedrin.

The idea that ‘All are dependent on the owner of the wheat’ is explained by Rashi as meaning that ultimately the basic knowledge of Mishnah and the final legal rulings are what is essential. The Meiri explains that even without keen abilities of analysis, someone with a breadth of knowledge will be able to compare and contrast different legal rulings, while the dialectician is more likely to err based on his reasoning, and will not be familiar enough with precedent to be certain that he is correct.

In addition to his monumental translation and commentary on the Talmud, Rabbi Steinsaltz has authored dozens of books and hundreds of articles on a variety of topics, both Jewish and secular. For more information about Rabbi Steinsaltz’s groundbreaking work in Jewish education, visit www.steinsaltz.org or contact the Aleph Society at 212-840-1166.

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.