The Coming Week’s Daf Yomi by Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz

This essay is based upon the insights and chidushim (original ideas) of Talmudic scholar Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, as published in the Hebrew version of the Steinsaltz Edition of the Talmud.

This month’s Steinsaltz Daf Yomi is sponsored by Dr. and Mrs. Alan Harris, the Lewy Family Foundation, and Marilyn and Edward Kaplan

Beitzah 28a-b

Since we are allowed to prepare food on Yom Tov, in the event that fresh meat is needed, slaughtering an animal would be permitted. (It is worthwhile to note that the only way meat could be kept fresh during Talmudic times – prior to the invention of refrigeration – was by keeping the animal alive until it was to be cooked.) Shechita – ritual slaughtering – must be done with a specially prepared knife that is perfectly smooth with no chinks or nicks. The Mishnah on our daf forbids sharpening a knife on Yom Tov, but the Gemara permits it under certain circumstances.

Rav Yosef rules that a knife which became dull can be sharpened, as long as it still can cut meat, even if it can only do so with some difficulty. Rashi explains that if it can no longer cut at all, sharpening it would involve serious labor that should not be done on the holiday. The Ba’al ha-Ma’or argues that such a knife no longer serves its purpose, and is therefore no longer considered a utensil. Sharpening it would create a new utensil on Yom Tov, which is certainly forbidden.

Another question that is raised is whether the shochet can present his knife to the community rabbi on Yom Tov. The Gemara records a disagreement in this case between Rav Mari brei d’Rav Bizna, who permits it, and the Rabbanan, who forbid it.

The obligation for the shochet who slaughters animals for the community to show his knife to the local scholar is a Rabbinic ordinance instituted both to ensure that kashrut is scrupulously kept and to honor the community rabbi. This tradition came to an end many years ago. Although during Talmudic times any individual could perform shechita, later on only professionals who studied the laws carefully were allowed to do it and were certified by the community Rabbis as experts who no longer needed further approval. Nevertheless, in some communities – particularly Hassidic communities – this practice is still followed to this day.

Regarding the discussion in our Gemara, the R”if explains that we may forbid the scholar to check knives on Yom Tov because we fear that the knife will be carried outside the 2000-cubit city limit. According to the Re’ah, the problem is that the scholar checking the knife plays the role of a judge, and courts are not allowed to operate on Yom Tov. The Rambam‘s explanation is that if the knife is found to have a nick, the shochet may come to sharpen it, which is, as we learned in the Mishnah, forbidden.

Beitzah 29a-b

Because we are able to prepare food on Yom Tov, it is possible for people to find themselves in a situation in which they discover that essential ingredients for the meal are missing. Obviously they can go to their neighbors, borrow raw ingredients, and return them after Yom Tov is over. The last few Mishnayot in our perek relate to such transactions.

The last Mishnah in the perek teaches that a person can go to his local storekeeper and ask for a specific number of nuts or eggs – that he intends to pay for after the close of the holiday – even though previous Mishnayot limit the permissibility of having him weigh meat (28a, b) or measure out liquids (29a).

The Tosafot R”id explain the difference as being whether the agreement appears to be a business transaction or simply a neighborly agreement. Weights and measures – especially when connected with a specific value (like the case in the Mishnah on 28b: “weigh for me a dinar’s worth of meat”) – are clearly business-related and are forbidden on Yom Tov since they are “weekday activities.” Counting out a certain amount of eggs or fruit is an everyday household activity, which does not carry with it the stigma of commerce, and would thus be permitted.

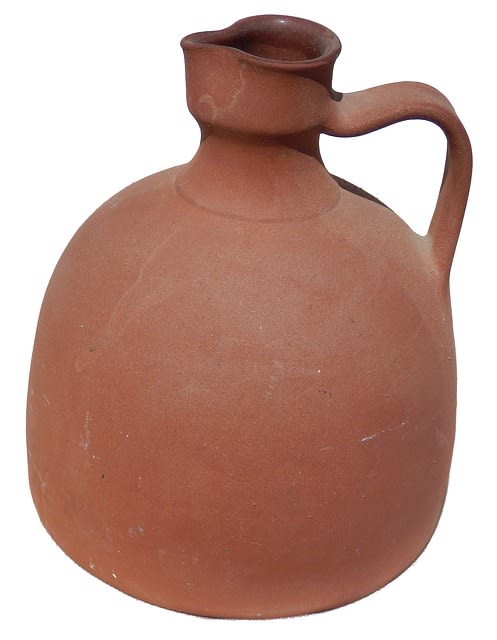

It is interesting to note that at least some of these discussions are not specific to Yom Tov. The P’nei Yehoshua points out that the discussion, found in the Mishnah on our daf, of whether a person can say “fill up this jug for me” if it is a measuring utensil, may be an appropriate question for Shabbat as well as for Yom Tov, since it is not specifically related to an issue of food preparation. As such, he asks, why is this Mishnah placed in Masechet Beitzah and not in Masechet Shabbat?

Several answers are suggested in response to this question. The Bigdei Yom Tov, for example, argues that, given the leniencies permitted with regard to food preparation on Yom Tov, we could logically conclude that we should allow for these activities, as well. It is therefore essential for the Mishnah to teach that weighing and measuring appear so much like forbidden business activities that we cannot permit them on Yom Tov, even for essential food preparation.

Beitzah 30a-b

Even those activities that are permitted on Yom Tov were limited by the Talmudic Sages in a variety of ways to ensure that people would respect the holiness of the day, lest it turn into another day of mundane activities. The passage in Sefer Yeshayahu (58:13) emphasizes the need to limit activities that are overly strenuous or take place in public settings and appear to be in conflict with the spirit of the day, even if they are permitted according to the letter of the law.

The fourth perek of Masechet Beitzah – perek ha-Mevi – deals with these issues. The opening Mishnah (29b) rules that a person who needs to transport kadei yayin – jugs of wine – should not carry them in a basket (a sal or a kupa); rather, they should be carried on one’s shoulder. Similarly, someone who needs to move a basket of straw on Yom Tov should not sling it onto his back, but should carry it in his hand. The general principle here is that transporting merchandise, even if it is needed for the holiday, cannot be done in the ordinary manner; rather, it should be carried in an out-of-the-ordinary manner to indicate that this is not everyday business, but is necessary for Yom Tov.

Based on this ruling, in Mehoza, where Rava was the community leader, the following regulations were instituted:

- People who ordinarily carry a heavy burden on their own (b’duhka) should use a simpler carrying pole (rigla).

- People who ordinarily use a carrying pole should have a second person assist them with it (b’agra).

- One who ordinarily carries a burden on his shoulders together with a second person should switch to a pole that is carried by hand (akhpa)

- If the hand pole is the normal way of carrying, then the object being carried should be covered with a sudar (scarf).

The Me’iri explains that the sudar, which acts to cover up what is being carried, makes the statement that the mover does not want to publicize the fact that he needs to transport this vessel on Yom Tov. (For more information on vessels used in Talmudic times, visit www.torahmuseum.com.)

Beitzah 31a-b

Since we are allowed to cook on Yom Tov, we are also permitted to add fuel to burning fires. Even so, wood or other fuel that is to be used should be prepared for that purpose before Yom Tov begins; otherwise it is considered muktzeh – set aside for a purpose other than to be burned. What wood is considered prepared for use as fuel on Yom Tov is the topic of discussion of the Mishnayot on today’s daf.

One of the Mishnayot discusses whether wood can be chopped for use as fuel, even if the wood was prepared for burning before Yom Tov began. As we learned on yesterday’s daf, the crucial question here is whether it appears to be a weekday activity; as such, the suggestion of the Mishnah is to chop the wood in an out-of-the-ordinary manner. Thus, using a kardom (spade), a megerah (saw), or a magal (scythe) is forbidden, while a kopitz (a knife for cutting bones) would be permitted.

It is interesting to note that the act of chopping wood is not, in itself, considered a forbidden act on Yom Tov. Many of the rishonim (Rashi, the R”id, and the Rashba, among others) argue that there is nothing intrinsically forbidden in making a large piece of wood into smaller pieces (unless it were turned into sawdust, in which case it would be forbidden because of the prohibition against grinding). According to this position, the reason some types of implements cannot be used is because they are clearly professional tools, and it appears that the person using them is participating in forbidden weekday activities. The Ra’avad explains that chopping the wood would generally be considered a forbidden activity, but it is permitted on Yom Tov as an essential part of food preparation. We limit the types of tools that can be used only because these activities should really be done prior to the onset of the holiday. Since proper preparations had not been done, the Sages insisted that they can only be done on Yom Tov in an unusual fashion.

Beitzah 32a-b

Although today we call a wax candle a ner, during the times of the Mishna the word ner referred to a clay lamp that held oil and had a spout in which a wick was placed and could be lit. While making a quality clay ner might involve significant work and effort, a simple ner could be made by taking a ball of clay, hollowing out the inside, where the oil was to be poured, and making an indentation in one of the sides that could be used for the wick.

The Mishnah on our daf teaches that if someone needs a ner for Yom Tov, he cannot be “pohet the ner,” since that would involve creating a utensil on Yom Tov, which is a forbidden activity. What exactly is involved in being pohet the ner is the subject of disagreement among the rishonim.

- Rashi explains simply that it means to create an indentation in the side of the clay ball, which would allow a wick to be placed in the oil.

- According to Tosafot, when the potter prepared the ner, he would open a hole for the wick and fill the hole with straw or other materials to keep it open. Removing the straw is considered completing the lamp, which is forbidden.

- The Rambam explains that the lamps were made in pairs, and after they were fired in an oven, they needed to be separated in order to be considered completed. Separating the lamps on Yom Tov is forbidden.

- According to the Ran, each lamp had a matching cover that was made to fit perfectly. Opening the cover of the lamp was considered the completion of the lamp.

As an example of a utensil that cannot be made on Yom Tov, the Gemara presents the case of the ilpasin haraniyot, or stew pots. These pots are described by the Talmud Yerushalmi as being made originally as one piece of clay. The potter would then cut off the top in order to make a cover, which was returned to the top of the pot in a loose manner. By doing so, when the pot – together with its cover – was placed in the oven to harden, both pieces would expand at the same rate. Thus, when removed, the cover would fit the pot perfectly. Upon purchasing the pot, the buyer would remove the cover with a small knock.

(For more information on vessels used in Talmudic times, visit www.torahmuseum.com.)

Beitzah 33a-b

The last several pages of Gemara have been dealing with preparing fuels used for burning on Yom Tov. As we have noted in our studies, burning fuel is permitted, as it is a prerequisite for cooking, which is permitted on Yom Tov. Nevertheless, according to the Mishnah on our daf, we are only allowed to add fuel to an existing fire or flame, but not to light a new fire.

The Mishnah teaches that a fire cannot be “brought out” (that is to say, lit) from wood, stones, dirt, tiles or water. Starting a fire with wood, stones and tiles would all be based on the same basic principles – the creation of heat or sparks by means of friction in the case of wood, or banging stones or tiles against one another (as is still done today in the case of modern cigarette lighters, for example).

Creating fire out of water means – as Rashi explains – using a water-filled glass instrument that works as a magnifying glass to create great heat by concentrating the sun’s rays on a particular spot.

There are a variety of explanations regarding how one can start a fire out of dirt. They include the possibility of pouring water on natural lime deposits in order to create a chemical reaction that produces heat, and using the heat created by decomposing organic matter.

The Gemara explains that starting a fire is forbidden on Yom Tov because it is molid -a creative activity. The rishonim disagree as to the level of severity of such an activity. The R”iaz, for example, says that it is not truly an act of creation, but since something new is now here, it is forbidden by the Sages. The Rambam‘s approach is to say that this is forbidden only because it could have been done before Yom Tov began.

Beitzah 34a-b

In preparing food to eat on Yom Tov, we must be sensitive to the fact that some foods involve so much hard work which can be done prior to the holiday that it is recommended they not be bothered with on Yom Tov or done only in an unusual manner. An example of this is cutting off excess leaves from vegetables, which cannot be done with the scissors that are normally used for this purpose. Even so, foods whose preparation is complicated can be cooked and eaten on Yom Tov. Kundas (artichokes) and akaviyot (cardoon) are examples of such foods. The kundas is identified as Cynara scolymus – the Globe artichoke – a perennial, thistle-like plant that grows to a height of one meter. Akaviyot are identified as Cynara cardunculus – cardoon – which is a member of the thisle family and related to the Globe artichoke.

Whole Globe artichokes are prepared for cooking by removing all but approximately 5-10 mm of the stem and (optionally) cutting away about a quarter of each scale with scissors, which removes the thorns that can interfere with the handling of the leaves while eating. And while the flower buds of the cardoon can be eaten much like the artichoke, the stems are generally made edible by blanching, when they are tied together and stored for some time.

Another type of food that cannot be eaten without effort is nuts. The Gemara quotes a baraita which permits wrapping nuts in cloth and cracking them, even if the cloth will tear. The Ran presents this as a case where several nuts are placed in a covering and broken all at once with a hammer. There is no concern that the cloth will tear, either because there is no intention to tear the cloth, or, as Rashi suggests, this is at worst a case of mekalkel – a destructive activity – which is not forbidden on Shabbat and Yom Tov.

In addition to his monumental translation and commentary on the Talmud, Rabbi Steinsaltz has authored dozens of books and hundreds of articles on a variety of topics, both Jewish and secular. For more information about Rabbi Steinsaltz’s groundbreaking work in Jewish education, visit www.steinsaltz.org or contact the Aleph Society at 212-840-1166.

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.