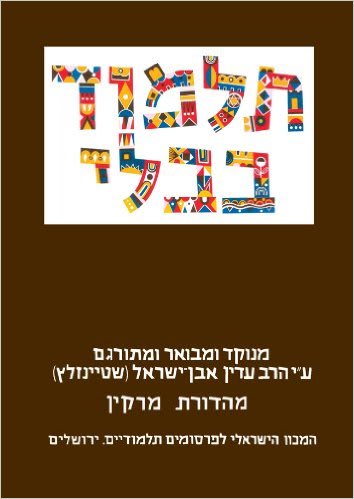

The Coming Week’s Daf Yomi by Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz

This essay is based upon the insights and chidushim (original ideas) of Talmudic scholar Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, as published in the Hebrew version of the Steinsaltz Edition of the Talmud.

Introduction to Masechet Bava Batra

Masechet Bava Batra – the “last gate” – is the third and final section of Masechet Nezikin, the large tractate that deals with financial matters.

Bava Batra differs from its predecessors, Bava Kamma and Bava Metzia, in two ways that are interconnected. While Bava Kamma and Bava Metzia dealt, on some level, with criminal matters, Bava Batra focuses solely on civil law. Parallel to this, the laws contained in the other two masechtot were often based on sources in the Torah and on the interpretation of the Sages, while our masechet is grounded in Rabbinic enactments whose sources are their understanding of human nature, on community agreements and on the need to establish boundaries and principles for business transactions in the Jewish community.

These principles are, of course, based on basic biblical principles that serve as the foundation for monetary matters:

- Not to take something that belongs to someone else (Vayikra 19:11, 13)

- The prohibition to trick or take advantage of another (Vayikra 19:11, 25:17)

- The general concept of Rabbinic ordinances based on doing what is “right and good” (Devarim 6:18).

Nevertheless, these rules and regulations will not suffice to create a system of laws that will govern the civil and economic communities. This need encouraged the Sages to create a system whose details would allow for development of a healthy society.

Given that the focus of Masechet Bava Batra is on monetary relationships, there is an intrinsic difference between the topics dealt with here and those that fall into the category of ritually forbidden matters. For example, one of the crucial powers of bet din is the ability to establish laws as is deemed appropriate. Given that hefker bet din hefker – that Jewish courts can declare property ownerless – they can take away someone’s property or transfer it to the hands of another. A further example is the ability of the person who holds the property to transfer or relinquish the rights granted to him by Jewish law. Thus, the regulations that we find in this Masechet serve to establish principles of law when two parties are in disagreement. If they can come to an agreement that satisfies both parties, they can choose to ignore the law.

There are four basic topics covered in this Masechet:

- Relationships between neighbors

- Working with legal proofs and documents

- Sales

- Inheritance law.

Much of what is discussed relates to the general meaning of the term chazaka, which is interpreted in different ways. In its broadest sense, a chazaka is an assumption that is made about the nature of human behavior – how do people ordinarily deal with certain situations and how does an average person interpret and understand an agreement. Similarly with regard to sales – what do ordinary people mean when they enter into certain standard agreements? While well-written contracts may spell out every detail, the court must know how to handle cases where the agreement was not clearly stated.

Another issue that falls under the broad category of understanding the intention of the two parties is the question of gemirut da’at – agreed intent of the parties to the transaction. Here the Gemara deals with questions like how to decide whether someone who is forced into an agreement actually means to accept its conditions, or if we have to throw it out entirely.

Since the rules and regulations governing these laws are not based on objective, biblical sources, there is more flexibility than we find in other areas of halacha, and we find that much is dependent on minhag ha-medinah – the common practice in a given community.

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.