The Coming Week’s Daf Yomi by Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz

This essay is based upon the insights and chidushim (original ideas) of Talmudic scholar Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, as published in the Hebrew version of the Steinsaltz Edition of the Talmud.

Bava Batra 140a-b

The ninth perek of Masechet Bava Batra, Perek Mi she-Met, began on yesterday’s daf. This perek, like its predecessor, deals with questions of inheritance. While the last perek focused on biblical inheritance laws, this perek deals with situations that arise out of rabbinic enactments and community minhagim.

One important rabbinic enactment, the ketubah, or marriage contract, includes a clause called ketubat bnan nukvan – “the daughter’s ketubah” – that guarantees that the daughters will be supported by the father’s estate until they marry or reach the age of maturity and become independent. The first Mishnah deals with the question of what to do when there is not enough money in the estate to support both the sons, who are entitled to inherit according to biblical law, and the daughters who are entitled to be supported according to rabbinic enactment.

According to the Tanna Kamma, in such a situation, the daughters should be supported even if the sons are forced to beg for their sustenance. The Tanna Admon objects to this ruling, saying “why should I lose out simply because I am male?”

Rabban Gamliel agrees with Admon’s comment.

The Gemara on our daf asks what Admon meant with his comment, and Abayye explains that he meant to say that he did not understand why being commanded to study Torah should make him lose his rights to his inheritance. Rava objects to this interpretation of Admon, pointing out that Torah study has no bearing on the right to inherit. Rav‘s explanation is that Admon was simply commenting that if there was a large estate, his rights as a male would give him priority in inheriting, and he did not understand why he should lose those rights if there was a smaller estate.

Although the Gemara in Ketubot (109a) states that whenever Rabban Gamliel supports Admon’s ruling that becomes the accepted halacha, in this case our Gemara seems to accept the position of the Tanna Kamma. Rabbeinu Tam suggests that perhaps in our Mishnah Admon is not arguing with the Tanna Kamma, but simply reacted in strong language to a ruling that surprised him – surprise that is echoed by Rabban Gamliel.

Bava Batra 141a-b

What are better, sons or daughters?

The Mishnah (140b) brings a case of a man who says regarding his pregnant wife “if a boy is born he should be given a maneh (100 zuz).” The Mishnah rules that if a son is born, he will be given that sum of money. Similarly, if the man says “if a daughter is born she should receive 200 zuz,” the child, if a girl, will receive that money. If the man says “if a boy is born he should receive a maneh, and if a daughter is born she should receive 200,” then if twins are born — one boy and one girl — then each will receive the money that was promised.

The Gemara on our daf wonders why all of the cases in the Gemara have the man offering a daughter more than a son — is a daughter better than a son? Several answers are offered by the Gemara:

Shmuel says that the case of the Mishnah is when it is a first born child, and this follows the teaching of Rav Chisda who said that a first born girl is a siman yafeh – a good sign – for future sons. Some say this refers to the fact that an oldest daughter will help raise her younger siblings, while others interpret it to mean that it helps avoid eyna bisha – the evil eye. The Maharsha explains this as stemming from the fact that a first born son will receive a double portion, which is bound to create a certain amount of jealousy and tension between brothers. If a daughter is born first, all of that tension dissipates.

Rav Chisda says simply that he found his daughters to be better than his sons.

The Rashbam explains this statement based on his understanding that all of Rav Chisda’s sons died during his lifetime. Rabbeinu Tam argues that some of Rav Chisda’s sons remained alive, and suggests that his daughters married men who were great sages and leaders of their generation. The Maharal says simply that Rav Chisda’s daughters were righteous and scholarly, and outshone his sons.

The Gemara concludes that the Mishnah may follow the opinion of Rabbi Yehuda who felt that daughters must be given more since it is more difficult for them to go out and support themselves than it is for sons to do so.

Bava Batra 142a-b

According to Jewish law, can a gift be given to an unborn child?

As we learned on yesterday’s daf, from the simple reading of our Mishnah, it would appear that a gift can be given to an unborn child. Nevertheless, the Gemara on today’s daf clearly rules that ha-mezakeh le-ubar lo kanah – that when someone attempts to give a gift to an unborn child – the kinyan, the act of ownership – does not take effect. How can this ruling be reconciled with the Mishnah that allows a father to give gifts to his unborn children? The Gemara explains that the case in our Mishnah is unique because da’ato shel adam kerovah etzel beno – a person’s thoughts are particularly close regarding his son.

From the Rashbam‘s commentary it appears that he interprets this answer as meaning that the problem with an unborn child taking possession of gifts does not stem from a difficulty with the kinyan, rather its source is the inability of the person giving the present to have sufficient da’at makneh – he cannot possibly have full intent to give the gift if the intended recipient is not yet in this world.

Another approach is suggested by Rav Hai Gaon, the Rambam, Ritva, and others. They explain the case of our Mishnah to be referring specifically to a case of a shechiv me-ra – someone on his deathbed – who is granted unique rights to divide up his property even without a kinyan as is ordinarily required. This enactment was established by the Sages out of sensitivity to the situation of someone who, in the last hours of his life, wants reassurance that his wishes are being fulfilled. According to this approach, the law that appears in the Mishnah is part of this unique enactment that is made so that the shechiv me-ra will not lose his sanity, since da’ato shel adam kerovah etzel beno. It would not work in any other case, however. In all other cases an unborn child is not considered to be a person who can take possession of property.

Bava Batra 143a-b

Our Gemara discusses the division of silk that was sent as a present by the father.

Rabbi Ammi teaches that when someone sends silk to his house, the pieces that appear to be prepared for men should be given to the sons, but those that appear to be prepared for women should be given to the daughters. This is true only if his sons are not yet married. If they are married, however, then we can assume that the silk was meant for his daughters-in-law, unless there were unmarried daughters, who we can assume were meant to receive the silk.

The difficulties involved in producing silk are such that even today real silk is a very expensive commodity. This was certainly the case in Talmudic times, when all silk was produced in China, and the distance to import such fabric was immense, given the realities of transportation at that time. With this in mind, we can well understand that dividing up even a small amount of silk would be a matter of importance within the family. It appears from the Gemara’s description that in this case the pieces were already colored or cut in ways that made it clear if the material was meant for men or for women.

It is clear that the case of the Gemara is not a situation of inheritance, for in such a case all of the material would be divided up according to ordinary inheritance laws, rather we are talking about someone who sent material to members of his household while he was still alive. Since we are not talking about an estate, the Ri”f quotes a statement from the Talmud Yerushalmi that says that even if the man simply sent this present “to my children” it would be understood to include daughters as well as sons.

Rabbeinu Chananel suggests that after he sent the present the man died. Apparently he understood that the simplest things to do would have been to ask the man how he meant to divide up the silk. Since the Gemara does not suggest this, we must assume that he was no longer available.

Bava Batra 144a-b

How much of what happens to us is in our hands, and how much is in God’s hands?

This question is the crux of a discussion about how much brothers will be responsible for each others’ illnesses.

The Mishnah on today’s daf teaches that brothers who are being supported by their father’s estate will share equally in profits or losses made by one of the brothers in a government position that he received based on his father’s connections. If one of the brothers becomes ill and must pay medical bills, he is responsible to pay that out of his own pocket.

In the Gemara, Rabin quotes Rabbi El’a as teaching that the sick brother is responsible for his medical bills only if he was the cause of his own illness. If he could not have prevented his illness, then all would share to pay for his medical care.

What illness is he responsible for? Rabbi Chanina taught – ha-kol b’yedei shamayim, chutz mi- tzinin u’pachim – all is in God’s hands, except for cold and heat. Thus a person is responsible to avoid illnesses caused by these things.

That tzinin u’pachim are in human hands is decided based on a passage in Mishlei (22:5) that teaches that tzinin u’pachim are stumbling blocks that an intelligent person knows to avoid. As far as the passage in Mishlei is concerned, most of the commentaries there agree that the words tzinin u’pachim mean thorns and obstacles. Nevertheless, in the context of our Gemara the term is interpreted in a number of different ways. Rashi and most of the commentaries on the Talmud understand it to mean “cold and heat.” The intention, however, is one. Most calamities that befall a person appear suddenly, and a person cannot possibly prepare himself for them. There are, however, calamities that a person brings upon himself because he is not careful and does not plan in advance.

Bava Batra 145a-b

What is more satisfying – facing the challenge of developing a deep understanding of one’s Talmud study, or being able to read simple straightforward Mishnayot?

Our Gemara quotes a passage in Mishlei (15:15), and brings a number of homiletic approaches to explain it. The simple rendering of the pasuk would teach that all the days of a poor person are difficult, but someone with a good heart has a continual feast. The Maharsha explains that none of the Sages choose to explain this passage to be referring to a poor person, since the parallel line in the second half of the pasuk does not refer to someone with monetary wealth, rather to someone with a “good heart,” i.e. someone who enjoys spiritual prosperity.

Rabbi Zeira quotes Rav as interpreting this passage to mean that the poor person is a ba’al Talmud, while the man with a good heart is a ba’al Mishna. Thus, someone who must struggle to analyze the ideas and concepts has a difficult time, in contrast with someone who studies the simple meaning of the Mishnah, who has a much easier time.

Rava argues that it is exactly the other way around – that the ba’al Mishna finds challenges in his learning, while the ba’al Talmud has it easier. Rabbeinu Gershom explains that the ba’al Mishna has so little to work with and must struggle in his study, while the ba’al Talmud is steeped in learning and finds much greater satisfaction in his study. The Maharal suggests that the ba’al Mishna reads and reviews with little comprehension, which is a source of pain and anxiety for him, while the ba’al Talmud finds pleasure and satisfaction in his study.

Other interpretations of this passage include:

- Rabbi Chanina, who suggests that it refers to someone with a bad wife or a good one.

- Rabbi Yannai, who interprets it as distinguishing between someone who is overly sensitive and someone who is more relaxed in his attitude.

- Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi, who argues that it differentiates between someone who is limited to a short term view of life and someone who can see the bigger picture.

Bava Batra 146a-b

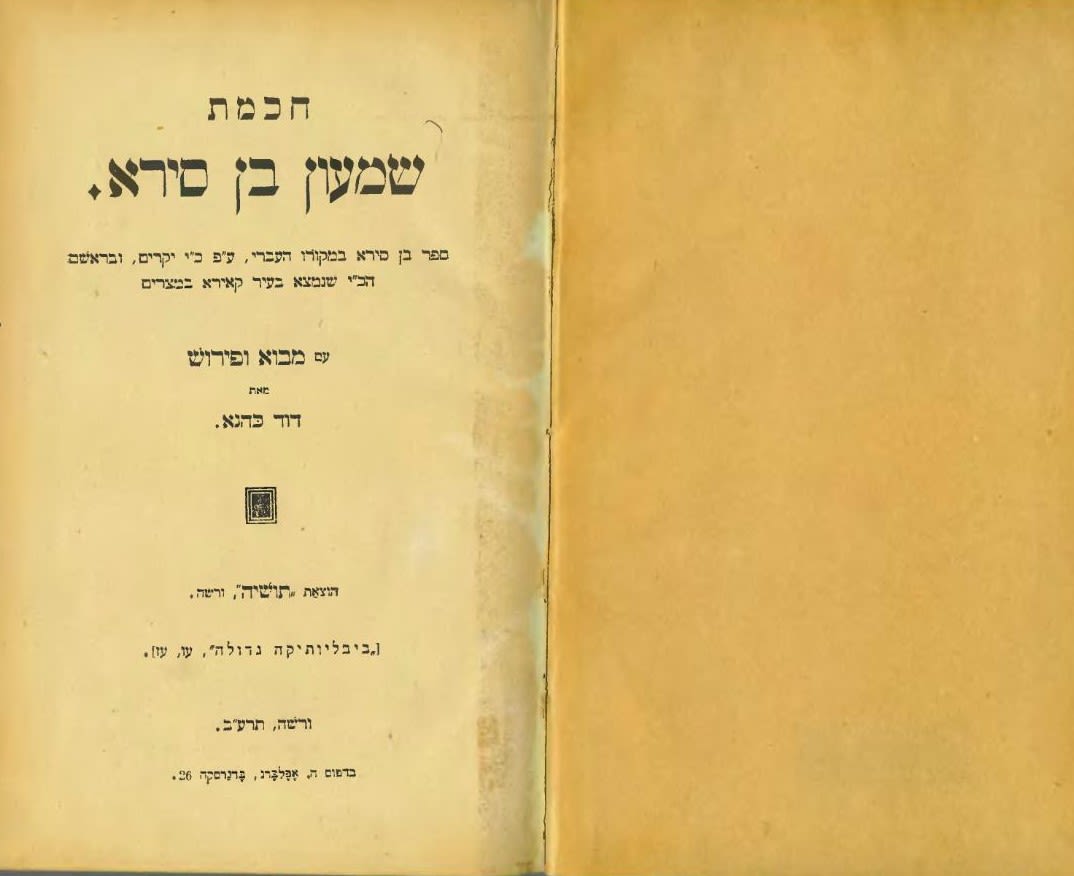

In discussing the plight of the poor, who cannot even enjoy improvement in their situation, the Gemara quotes Sefer Ben-Sira as saying that “All the days of a poor man are bad,” for even Shabbat and the holidays are difficult for him. Furthermore, Ben Sira is quoted as saying, “The nights also. Lower than all the roofs is his roof, and on the height of mountains is his vineyard, so that the rain of other roofs pours down upon his roof and the earth of his vineyard is washed down into the vineyards of others.“

These statements are based on the passage in Mishlei (15:15), and the quote appears to be additional insights that are attributed to Ben Sira.

Sefer Ben-Sira is one of the earliest books composed after the closing of the Biblical canon. It was authored by Shimon ben Yehoshua ben Sira, a native of Jerusalem, who was a younger contemporary of Shimon ha-Tzaddik, prior to the Hasmonean era. The book of Ben-Sira was held in great esteem, and after its translation into Greek by the author’s grandson (in the year 132 BCE in Alexandria), it because widely known even among those who were not familiar with the Hebrew language. Sefer Ben-Sira is included as a canonical work in the Septuagint (and therefore is considered such in many other translations of the Bible), and although the Sages chose to view it as one of the sefarim chitzoni’im – books outside of the canon – they quote it in a respectful manner throughout the Talmud, sometimes even referring to it as Ketuvim. Still, because of confusion between this work and another one that was known as Alfa-Beta d’Ben-Sira, which was a popular – and problematic – work, we find statements in the Gemara forbidding the study of Sefer Ben-Sira.

For generations Sefer Ben-Sira was known only from its translations, but recently parts of it have been found in the original Hebrew (in Masada and elsewhere). Since it was not part of the official Biblical canon it appears that the copyists felt more freedom when working with it and we find several different versions of the same text. When it appears in the Talmud it seems likely that it is being quoted by heart by the Sages, rather than from a written text. The statements quoted in our Gemara, for example, are not found in extant translations or manuscripts of Sefer Ben-Sira.

In addition to his monumental translation and commentary on the Talmud, Rabbi Steinsaltz has authored dozens of books and hundreds of articles on a variety of topics, both Jewish and secular. For more information about Rabbi Steinsaltz’s groundbreaking work in Jewish education, visit www.steinsaltz.org or contact the Aleph Society at 212-840-1166.

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.