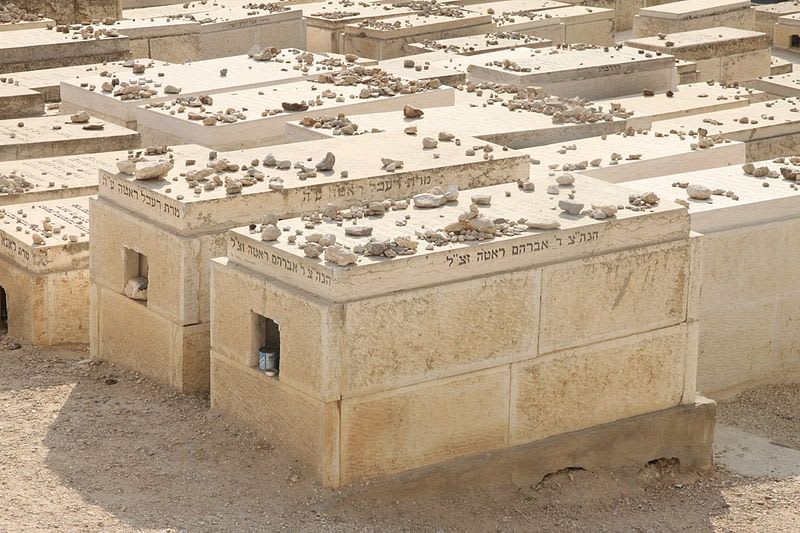

(preoccupation with burial)

Part of the special recitation made on disposing of all tithes is “I did not eat any [maaser sheni] in my aninut” (Devarim 26:14). This verse is one of the main Torah sources for the special status of aninut, the period between the death of a close relative and the time when his or her burial has been completely taken care of (Tur YD 398). Let us examine the special character of this unique period.

The ordinary rules of mourning begin when the body is buried. Until that time, everything surrounding the death is in a state of dislocation; but when the body is returned to its place of origin in the earth then the entire process of reconciliation begins:

At burial, the body of the departed begins to be absorbed and accepted by the earth, and so finds rest in its place of origin. The soul is completely freed from the body, which is now completely hidden and is in no way suited to be the abode of the soul, and so may begin its journey into the world of souls, to be judged and receive its appropriate reward in the next world. And the mourners have completed their practical obligations towards the deceased, and through the act of burial demonstrate that they have completely reconciled themselves to the passing of their relatives.

Before the burial, the relatives do not yet begin to mourn but rather are in a special state known as “aninut”. At this time the mourner is preoccupied with the burial; eating meat and drinking wine is forbidden, and the mourner is exempt from all positive mitzvot. Even if he or she wants to, the onen may not pray, say blessings, and so on. Two complementary explanations are given for this status in the legal works.

HONOR OF THE DECEASED

The Yerushalmi mentions two possible reasons for this status. (Yerushalmi Berakhot 3:1.) One is that the exemption is to honor the deceased. The relatives are charged with the heavy responsibility of taking care of the preparations for burial; they have to do this only once, and they will never have another chance to do it properly. It would be unseemly for them to be occupied with any other activity – even a mitzva. It would look as though they are neglecting their loved one. (See Bach YD 341.)

OCCUPIED WITH A MITZVA

The other possibility is because of preoccupation with the burial. Many commentators elaborate this idea by pointing out that concern with the needs of burial is a mitzva. There is a general principle in Jewish law that “One who is occupied with a mitzva, is exempt from another mitzva”. (Responsa Bach II:52; Responsa Chatam Sofer I:17.) Each mitzva is precious, and needs to be done with all our heart.

Even if the second mitzva seems to be more important, it can’t displace the first one (with rare exceptions). “Be as careful with a light mitzva as with a grave one; for it is impossible to know the reward for each mitzva”. (Avot 2:1.)

For this reason any person who is guarding a dead body (which is never left alone – YD 339:4) is exempt from regular prayers – even if he or she is not a family member. (SA YD 341:6.)

WHICH REASON IS PRIMARY?

The Shulchan Arukh rules that even relatives who are not actively involved with the burial are obligated in aninut (YD 341:1) ” suggesting primacy of honoring the dead. Yet we also hold that once the burial is being taken care of by the chevra kadisha, aninut is over (YD 341:3) ” suggesting primacy of occupation with burial. One understanding is that both reasons apply. Alternatively, we may say that the two explanations are complementary: Preoccupation with the burial is itself a way of showing respect for the deceased: The very fact that family members make themselves available to help if they should be needed is a mitzva which shows their devotion to their departed relative.

Rabbi Asher Meir is the author of the book Meaning in Mitzvot, distributed by Feldheim. The book provides insights into the inner meaning of our daily practices, following the order of the 221 chapters of the Kitzur Shulchan Aruch.

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.