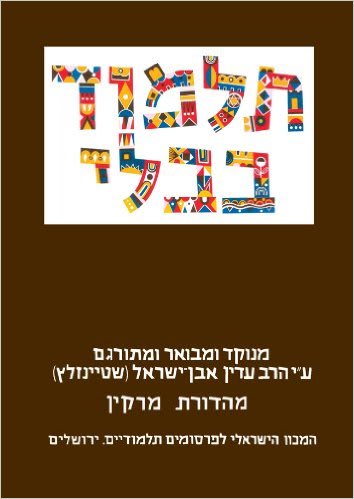

The Coming Week’s Daf Yomi by Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz

This essay is based upon the insights and chidushim (original ideas) of Talmudic scholar Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, as published in the Hebrew version of the Steinsaltz Edition of the Talmud.

This month’s Steinsaltz Daf Yomi is sponsored by Dr. and Mrs. Alan Harris, The Lewy Family Foundation, and Marilyn and Edward Kaplan

Introduction to Masechet Sotah

Masechet Sotah deals mainly with the laws surrounding a Sotah (see Bamidbar, Chapter 5) – a woman whose husband suspects her of infidelity, who is brought to the Temple to be tested by drinking specially prepared “bitter waters.” Although checking the woman in this manner is supposed to lead to her death if she committed adultery, the purpose of the ceremony is not to bring about destruction, rather it is to being about peace between husband and wife. According to all opinions in the Gemara, a man who comes to despise his wife because he suspects that she has committed adultery has the right to divorce her. In our case, however, we are dealing with a man who does not want to divorce his wife, but nevertheless is suffering from jealousy and a fear that his wife has been unfaithful. His desire is to clarify the situation so that he can return to a state of security in his marriage. Through the ceremony of Sotah, the Torah offers a unique method of reaching certainty in this matter.

Although the purpose of Sotah is to assure marital peace and harmony, it is important to point out that the ceremony is not performed simply because the husband demands it. As is explained in the Gemara, it is only after a man warns his wife in the presence of witnesses that due to his suspicions he does not want her to spend time privately with a specific person – and witnesses step forward testifying that she did so – that the process of Sotah can begin. Thus, the woman, who is first warned about her husband’s concerns, has certainly behaved inappropriately and the suspicions about her behavior appear to be well-founded.

If the woman committed adultery, aside from the fact that she transgressed one of the most serious prohibitions of the Torah, her behavior is considered to be “animalistic” – ma’aseh beheima – the make-up and fancy clothing notwithstanding. This is why she is treated in a degrading manner when she is brought to the Bet HaMikdash for the ceremony – the kohen tears her upper clothing, tying them with a rope, and he removes her hair covering. Similarly, the mincha sacrifice that she brings is brought from barley flour (barley was viewed by the Sages as animal feed) and it does not include oil like other menachot. The “bitter waters” were drunk out of a simple earthen vessel.

The laws of Sotah include a unique aspect that does not exist in any other mitzvah of the Torah. Sotah is the only mitzvah that is dependent on a miraculous occurrence. The idea that drinking water should be able to test whether a woman has committed adultery is not a natural phenomenon. Only a miraculous event could create a situation where the woman will die if she was unfaithful, but will be a blessing for her if she was suspected for no reason. Furthermore, according to the Sages, if she committed adultery, not only would she suffer upon drinking the water, but her lover would, as well, even if he was nowhere near the Temple.

Another unique element of the mitzvah of Sotah is that preparing the water involved the deliberate erasing of biblical passages – including God’s name – something that is forbidden under other circumstances.

It should be noted that according to the Sages there are a number of reasons why the Sotah waters might not work – including the possibility that the husband himself was involved in sexual misbehaviors, or if the woman had some positive attributes that would protect her. Since not every generation is on a high spiritual level that would allow for a miracle like this to take place, around the time of the destruction of the second Temple, the practice of Sotah was discontinued.

We find quite of bit of aggadic material in Masechet Sotah, most of which stems from the nature of the topics discussed in it. The commandment to make the suspected woman drink the bitter waters, which involves a supernatural element in the life of the couple, leads to discussions about such elements as reward and punishment, what makes people sin and so forth – not only for a Sotah, but for personalities throughout Jewish history, as well.

Sotah 2a-b

The first Mishnah in Masechet Sotah opens with the words ha-mekaneh le-ishto – when someone is “jealous” of his wife – and begins the process of warning her not to be in private quarters with a specific man, a process that will lead to her drinking “the bitter waters” of Sotah if she does so.

As Rashi explains, the term ha-mekaneh is based on the pasuk, or verse (Bamidbar 5:14) that describes the husband’s concern using the words ve-kinei et ishto. Nevertheless, the definition of the word kinei is not simple, since we find it used with two different meanings. Generally speaking, the usage kinei be-…is understood to mean jealousy – a desire for something that is owned by another that a person wants to have (see Mishlei 24:1, 19). The usage kinei le-… however, is understood to indicate a protective love, anger at someone who injures or tries to attack something that is important to the me-kaneh (see, for example, Eliyahu‘s argument kano kineti la-Shem in I Melakhim 19:10, 14).

The common ground between these two meanings may be the heartfelt emotion that is caused by another. The kin’ah that is discussed in Masechet Sotah is of the latter type, although, as our Gemara points out, the root word may also be used here meaning a threat or warning, as in the passage ke-ish milhamot ya’ir kin’ah, yari’a af yatzri’ah (Yeshayahu 42:13) describing God as shouting during warfare. This is the approach of the Rambam in his Commentary to the Mishnah; the Tosafot Yom Tov suggests that in our context the term may refer to anger. The different translations may depend on whether the act of kinuy is seen as permitted for the husband to do, or if it is really something that he should be discouraged from doing.

Sotah 3a-b

Our Gemara brings a number of statements in the name of Rav Chisda, whose origins are found in the halacha of a Sotah:

- Adulterous behavior in the home is like a worm in the sesame – i.e. just as the worm destroys the sesame, adultery destroys the fabric of the family

- Anger in the home is like a worm in the sesame

- Before the Jewish People sinned, the heavenly presence was manifest in every person, as the Torah teaches (Devarim 23:15) that God walks in the camp; once the Jewish People sinned, God’s presence was removed, as that pasuk concludes, that no promiscuity should be shown, or He will leave you.

According to most of the commentaries, the third statement quoted in the name of Rav Chisda is a continuation of his first two observations. As long as a married couple behaves appropriately, God’s presence resides among them. Should they begin to behave inappropriately, His presence will leave them. The Maharshah suggests that this idea is similar to one that appears later on in Masechet Sotah (17a), that a husband and wife – ish ve-ishah – who are worthy will find God’s holy presence among them (the words ish ve-ishah include the letters of God’s name – yod and heh). If, they sin, however, God’s presence departs and we are left with destruction (without the letters yod and heh, the words ish ve-ishah become esh – fire).

The Maharal suggests that God’s blessing rests on a home that is built on the correct values and ideals. Should the couple destroy the natural order by illicit sexual behavior that is driven by lust or anger, God cannot reside in a place that is built on such inappropriate values. The Meiri suggests simply that ordinarily a person receives Godly attention – hashgaha peratit – in this world, unless his sin causes God’s presence to leave him, in which case he will be left to the vicissitudes of the forces of nature.

Sotah 4a-b

As we have learned, in order for the laws of Sotah to come into play, the husband must warn his wife that she should not be secluded with a certain man, and his warning notwithstanding, she does exactly that. In order for the seclusion to be considered significant, it must be long enough for the man and woman to have engaged in at least the beginning of an act of sexual intercourse. Several suggestions are raised with regard to the definition of that length of time:

- Rabbi Yishmael says, it is the amount of time it takes to walk around a date palm

- Rabbi Eliezer says it is the amount of time it takes to prepare a cup of wine

- Rabbi Yehoshua says that it is the amount of time it takes to drink it

- Ben Azzai says the length of time it takes to roast an egg

- Rabbi Akiva says the amount of time it would take to eat it

- Rabbi Yehuda ben Beteira says the amount of time it would take to swallow three eggs

- Rabbi Eliezer ben Yirmiyah says sufficient for a weaver to knot a thread

- Chanin ben Pinchas says enough time for a woman to extend her hand to her mouth to remove a chip of wood from between her teeth

- Pelimo says sufficient for her to extend her hand to a basket and take a loaf.

After listing all of these different opinions, Rav Yitzhak bar Rav Yosef quotes Rabbi Yochanan as saying that each of the Sages based his statement on his personal experience with sexual relations. To the objection that ben Azzai was single, the Gemara offers three possible explanations:

He had been married, but he left his wife

He was quoting what he learned from his teacher

Sod ha-Shem le-yere’av (see Tehillim 25:14) – those who fear God have hidden knowledge, even of things that they did not experience personally.

Although ben Azzai never received formal Rabbinic ordination, he was considered one of the great scholars of his generation. Apparently he did not learn until he was an adult, when he met Rabbi Akiva‘s daughter who promised to marry him if he studied Torah. Although it is clear that he did so, we do not know whether he actually married her or not. If he married her, he soon divorced her, because his desire for Torah study did not allow him time to live a normal family life.

Sotah 5a-b

Today’s daf focuses – almost in its entirety – on the evils of gasei ha-ruach – of haughtiness, of conceit. A lengthy list of Sages offer proof texts from Tanach all of which clearly indicate that pride is a destructive force.

One example is the teaching presented by Rabbi Alexandri, who says that someone who is a person with gasut ha-ruach will be destroyed by even the lightest of winds, based on the pasuk, ve-ha-resha’im ka-yam nigrash (see Yeshayahu 57:20). Rabbi Alexandri explains that if the ocean – which contains many rivi’iyot (a revi’it is a liquid measurement – one quarter of a log) is pushed and pulled by the wind, certainly a human being who has just one revi’it of blood will be buffeted by the wind, as well.

This teaching is difficult since we know that a human body has much more than a single revi’it of blood, something pointed out by the rishonim. While some suggest that Rabbi Alexandri is referring to a baby, even so we must explain that the intention is the amount of blood whose removal would put the child in danger, since even a baby has more than a revi’it of blood in his or her body. Another suggestion is that this statement refers to the amount of blood that is in the human heart. This explanation works well with the fact that every heartbeat expels about 80 cubic centimeters of water, which is approximately equivalent to a revi’it.

Somewhat surprisingly, the Gemara continues with the statement of Hiyya bar Ashi who quotes Rav as saying that it is essential that a Torah scholar should have some small amount of gasut ha-ruach – he says “one eighth of one eighth” – which, Rashi explains, is the smallest measurable amount that has its own name. Rav Huna the son of Rav Yehoshua teaches that such gasut ha-ruach crowns the scholar like a sasa crowns the stalk of wheat. The Meiri explains this simile by saying that just as the sasa protects the wheat, similarly a minimal amount of pride will protect the scholar from being looked down upon by others.

In addition to his monumental translation and commentary on the Talmud, Rabbi Steinsaltz has authored dozens of books and hundreds of articles on a variety of topics, both Jewish and secular. For more information about Rabbi Steinsaltz’s groundbreaking work in Jewish education, visit www.steinsaltz.org or contact the Aleph Society at 212-840-1166.

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.