The Coming Week’s Daf Yomi by Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz

This essay is based upon the insights and chidushim (original ideas) of Talmudic scholar Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, as published in the Hebrew version of the Steinsaltz Edition of the Talmud.

Sanhedrin 42a-b

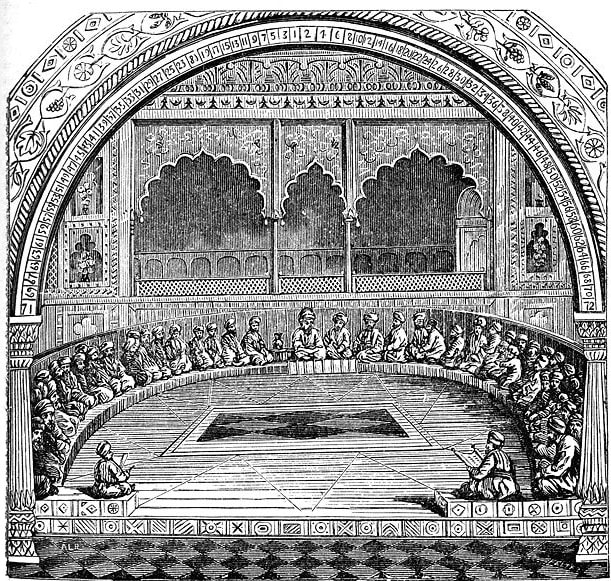

The previous perakim of Masechet Sanhedrin dealt with the court system and the legal procedures necessary to try capital cases according to Jewish law. The sixth perek – Perek Nigmar Ha-din – focuses on questions about how the death penalty was carried out. Before applying the court’s decision, every possible precaution was taken to ensure that there should not be a miscarriage of justice. Thus, even unlikely scenarios are considered in an attempt to ensure that even in the last moments of his life, new evidence would be considered on behalf of the convicted prisoner.

According to Jewish law, carrying out the death penalty is not only performed out of a sense of protecting the community by removing a dangerous person from its midst, it is also the fulfillment of a Torah obligation incumbent upon the bet din, and like all mitzvot it has many requirements and details. Thus this chapter covers such topics as the location where the punishment will be carried out, the means by which it will be carried out, upon whom is it incumbent to carry out the punishment and so forth.

The importance of fulfilling this commandment impacts not only on society at large, but aims to affect the convicted man, himself. The punishment that he receives acts as partial penance for his crime; the purpose of his viduy – admission of guilt – at the time that the death penalty is carried out is not to reassure all assembled that justice was done, rather it is the beginning of the process of the forgiveness that he will receive.

Among the mitzvot of the Torah are some that are distasteful, yet they are included in the corpus of Torah commandments and they have significance and importance. Clarifying the rules and regulations that govern these commandments must be done with the same level of care and concern that other mitzvot receive, and even these commandments require kavana – proper intent – to fulfill the mitzvah as commanded. The principle ve-ahavtah le-re’akhah kamokhah – you should love your neighbor as yourself – applies even when a person is condemned to death. Even here the Torah requires that the court concern itself with the condemned man’s best interests, to the best of its ability.

Sanhedrin 43a-b

Today’s daf includes a section of the Gemara that was censored and does not appear in standard texts of the Talmud.

The Mishnah on today’s daf teaches that before the condemned man is taken to be killed a public announcement is made: So-and-so the son of So-and-so is to be taken to be killed by stoning for committing a particular capital crime. Anyone who has anything to say on his behalf should come forward to speak up for him.

The Gemara makes a point of noting that according to the Mishnah the public announcement is made at the time that the death penalty was to be carried out. This stands in apparent contradiction with the following story that appears in a baraita:

On the eve of the Passover Yeshu was hanged. For forty days before the execution took place, a herald went forth and cried, ‘He is going forth to be stoned because he has practiced sorcery and enticed Israel to apostasy. Anyone who can say anything on his behalf, let him come forward.’ But since nothing was brought forward in his favor he was hanged on the eve of the Passover.

The Gemara concludes that Yeshu’s situation was unique since he was connected with the government. Since the government was interested in his case, the Jewish court wanted to ensure that everyone would recognize that he was given every opportunity to defend himself.

Having mentioned Yeshu, the Gemara lists his five disciples, Matthai, Nakai, Nezer, Buni and Todah, all of whom are presented as offering biblical proof that they should not be killed based on how their names appear in Tanach, and the Sages respond with corresponding passages that show that these names – and the people attached to them – can be destroyed.

All of the Talmudic stories that refer to Yeshu are confusing and difficult to understand, particularly since they do not parallel stories about Jesus that appear in other sources. It is possible that we have hints here to incidents that were not preserved in other traditions.

Sanhedrin 44a-b

Even today, when death sentences are carried out in civilized countries that have a death penalty, the condemned is asked to confess and show regret for the crime that he committed.

The Mishnah teaches that Jewish law strongly encourages this behavior. According to the Mishnah (43b), when the condemned man was ten cubits from the place of execution the court-appointed individuals who escorted him would tell him to confess, since by doing so his execution would serve as an atonement for him and he would receive a share in the World-to-Come.

The source for this, which is discussed in detail on today’s daf, is the story of Achan who stole from the city of Yericho after it was set aside for destruction by God and Joshua (the entire contents of the conquered city was declared to be cherem – see Sefer Yehoshua Chapter 7). We find that Achan clearly confesses to his crime in pasuk 20, and the Mishnah concludes that his confession was accepted and served as atonement based on Yehoshua’s response in pasuk 25 where he says that God would punish him “on this day,” indicating that he would receive his portion in the World-to-Come.

By a homiletical examination of the passages that describe the process by which Achan was found guilty, the Gemara interprets his actions to have included a wide variety of inappropriate acts, aside from stealing from the cherem. Rabbi Abba bar Zavda suggested that he committed adultery with a married woman; Rabbi Il’a quoted Rabbi Yehuda bar Masparta as saying that he denied the mitzvah of circumcision. Furthermore, he said that the passage listing all of the things that Achan did (see Yehoshua 7:11) repeats five general transgressions, indicating that he violated all five books of the Torah.

The Kli Yakar suggests that since all five of the books of the Torah teach that it is forbidden to steal, clearly Achan transgressed them all. The Ramah points to specific commandments that appear in each of the five books: circumcision in Bereshit, stealing in Shemot, taking from the cherem in Vayikra, taking that which is not his, as appears in Bamidbar and putting it among his own possessions, as appears in Devarim.

Sanhedrin 45a-b

According to the simple reading of the passage in Sefer Devarim (21:22), someone who receives a death penalty will subsequently be hanged (and removed by nightfall). This reading of the Torah is rejected by both Rabbi Eliezer and the Chachamim in the Mishnah. Rabbi Eliezer restricts it to people who are condemned to death by stoning; the Chachamim limit it further, only to people who are killed for blasphemy or idol worship. Another disagreement between the tanna’im relates to hanging women. While Rabbi Eliezer requires that women who are condemned to death be hanged, albeit with their faces to the pole, the Chachamim rule that women are not hanged at all. Rabbi Eliezer responds by referring to the fact that Shimon ben Shetach was known to have hanged women in Ashkelon. The Chachamim answered him saying that Shimon ben Shetach’s ruling – condemning 80 women – was clearly extra-judicial, since a bet din cannot try more than one case every day.

The story in which Shimon ben Shetach hanged 80 women is Ashkelon appears in the Talmud Yerushalmi in Masechet Chagigah. As related there, when Shimon ben Shetach was appointed as nasi he was told that there were 80 witches in a cave in Ashkelon. In order to trick them he came on a rainy day together with 80 young men who were each given a jar with a dry cloak in it. He told them that upon hearing his signal they should put on the dry cloak and come in to lift the witches off the ground, which would steal their powers from them. Shimon ben Shetach called for the witches to open the cave door so that he could enter. Upon doing so he impressed them, entering in a dry cloak, and told them that he came to learn and to teach. Each of the witches conjured up part of a festive meal and then inquired as to what magic he could do. He offered to make 80 young men appear in dry cloaks who would sweep them off their feet. Giving the signal, the men entered and captured the witches, who were taken off and hanged.

The story concludes that relatives of those witches who were angered by this came forward with false testimony accusing Shimon ben Shetach’s son of a capital crime. Upon being convicted and led to his death the witnesses recanted, but the son insisted that the punishment be carried out, since he feared that people would suspect that the Sages showed favoritism to him by allowing the witnesses to change their minds, something that would weaken the efforts that his father had made in strengthening these laws.

Sanhedrin 46a-b

Among the most scrupulously kept traditions in Judaism are burial practices. Somewhat surprisingly the source for these practices is found in the laws of capital punishment.

According to the Torah, after the death penalty is carried out by the courts, the condemned man is hanged (see Devarim 21:22-23), but then is immediately removed and buried on that same day. The Mishnah on today’s daf explains that this law applies not only to individuals who are killed for committing capital crimes, but also to anyone who dies. Thus Jewish law requires burial to take place as quickly as possible, unless it will honor the deceased to arrange for his burial to be pushed off for a short time.

The Gemara relates that Shevor Malka – the Persian King Shahpuhr – asked Rav Hama if he could bring a biblical source for the Jewish law requiring burial of the dead. Rav Hama was unable to respond. Upon hearing this Rav Aha bar Yaakov became angry, arguing that Rav Hama should have referred to the above-mentioned passage in Sefer Devarim. In defense of Rav Hama the Gemara argues that the passage can be understood as a requirement to prepare a coffin, but not to actually bury the deceased. Other suggestions, e.g. that the Avot were all buried, or that God Himself buried Moshe Rabbeinu, are also rejected since they may only be evidence of a tradition, and not a true halakhic requirement.

Shevor Malka was the name of a number of Persian kings. Our Gemara is apparently referring to the second king Shahpuhr, who lived during the 3rd and 4th generation amoraim in Bavel. He was a zealous supporter of Zoroastrianism, a religion that he tried to impose on the minorities under his rule – especially Christians.

The discussion in our Gemara should be understood in the context of the Persian belief that in-ground burial defiles the earth, which is why Rav Hama, who appears to have been the official Sage of the Diaspora community, was required to respond to questions about why it was so important to Jewish law and tradition.

Sanhedrin 47a-b

On yesterday’s daf we learned about King Shahpuhr of Persia who made inquiries regarding the Jewish custom of burying in the ground in Bavel, a practice that stood in harsh conflict with the Persian view that the earth would be defiled by such burial.

In contrast, the Gemara on today’s daf relates that people would go to Rav’s burial place and collect dirt that was used medicinally for a certain type of fever. When this was reported to Shmuel, with an apparent complaint that Rav’s grave was being used inappropriately, his response was to permit the practice, since the dirt is karka olam – merely earth – that does not become consecrated because he was buried there.

Rabbeinu Yehonatan rules that this is true of any dirt around a grave, even if it was dug up and replaced to bury the corpse; once returned to the earth it remains karka olam and has no special status. Other rishonim disagree and limit this to situations where the dirt around the grave was undisturbed, e.g. when the burial took place in a cave; if it was dug up and moved around when the grave was prepared it became set aside in honor of the dead, and cannot be used.

Another issue relating to burial discussed on today’s daf involves the time that aveilut – the mourning period – begins. Mourning begins only after the burial is complete. According to Rav Ashi, that is only after setimat ha-gollel – when the gollel is sealed.

The commentaries disagree about how to define a gollel. Rashi explains that it is the cover to a casket. Tosafot suggest that it is a rounded stone that was used to close up a burial cave (several such stones have been found near ancient burial caves in Israel). During the times of the Mishnah, common burial practice was to place the body in a temporary grave where it would decompose. At a later date, the bones would be removed and transferred to a family burial cave. The round shape of the gollel stone allowed it to be rolled, closing the cave, yet easily opened when necessary.

Sanhedrin 48a-b

Much of this perek has focused on the laws that govern how the bet din carries out capital punishment. There are also extra-judicial punishments that can be meted out by the government in times of need. Thus, if a Jewish king found that an individual had sinned against the monarchy, he could arrange for him to be tried and killed.

The Gemara on today’s daf quotes a Tosefta that distinguishes between harugei malchut – people who are put to death by the king – and harugei bet din – those who are killed by the courts. While the children of harugei bet din receive their inheritance from the condemned man as they would had he died of natural causes, the inheritance of harugei malchut is confiscated by the king. Rabbi Yehuda disagrees, arguing that even the property of harugei malchut would go to their children.

The source for the first opinion, which is raised as a response to Rabbi Yehuda is the case of Navot ha-Yizraeli. According to the story in I Melakhim, or Kings (21:18), King Achav wanted to purchase a vineyard from Navot, who refused to sell it to him since it was his family inheritance. Seeing how disappointed King Achav was, his wife Queen Izevel assured him that she would take care of the matter and arrange for false witnesses to testify that Navot had cursed the king. Once Navot was duly killed, the navi recounts that King Achav took possession of the field, an action that led to a sharp rebuke from the prophet Eliyahu who said ha-ratzahtah ve-gam yarashtah!? – have you murdered and then expect to inherit!?

The Me’iri points out that the only time that the property of harugei malkhut would be confiscated by the king was when the person was killed on account of his having rebelled against the monarchy. If, however, he was killed because of some other pressing social need, e.g. a person who was known to be a murderer based on clear evidence that was not accepted in the ordinary courts because he had not been properly warned of the punishment that he would receive, then his children would receive their inheritance as in a normal case of their father’s death.

In addition to his monumental translation and commentary on the Talmud, Rabbi Steinsaltz has authored dozens of books and hundreds of articles on a variety of topics, both Jewish and secular. For more information about Rabbi Steinsaltz’s groundbreaking work in Jewish education, visit www.steinsaltz.org or contact the Aleph Society at 212-840-1166.

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.