The Coming Week’s Daf Yomi by Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz

This essay is based upon the insights and chidushim (original ideas) of Talmudic scholar Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, as published in the Hebrew version of the Steinsaltz Edition of the Talmud.

Sanhedrin 35a-b

The Mishnah (32a) taught that dinei nefashot – capital cases – cannot be judged at night. They are judged during the day and concluded during the day.

The source for this, according to our Gemara, is a passage in Sefer Bamidbar (25:4) that teaches that after the Children of Israel engaged in sexual relations with the daughters of Moav, Moshe was commanded to punish the people who were involved by hanging them neged ha-shemesh – facing the sun – i.e. during the day. Having engaged in forbidden sexual relations as well as idol worship (see 25:2-3), the perpetrators were liable to receive a death penalty.

According to today’s Gemara, this command demands explanation, for Moshe was not told to punish the perpetrators, rather he was commanded to take kol rashei ha-am – the leaders of the people. The Gemara asks: If the people sinned, what was the responsibility of the leaders?

In response, Rav Yehuda quotes Rav as offering a radically different interpretation to the pasuk. According to Rav’s approach, the leaders were not to be punished, rather Moshe was commanded to assign them to play the role of judges and set up courts of law to try the people who sinned. The Gemara explains that the need for many courts to be established did not stem from a technical rule that forbids a court from judging two people on a given day, since Rav Chisda taught that many people can be tried on the same day if it is for the same offense. Rather the need for many courts was to “remove God’s anger” (as indicated in the closing words of Bamidbar 25:4).

Rashi’s explanation of this idea is that by setting up courts to judge these cases, God will see that the nation is working zealously to defend His honor and will therefore turn away His anger. The Ramah suggests that it would take a significant amount of time were a single court to try all of the cases, and as long as evildoers exist in the world, God’s anger is manifest. By establishing many courts the evildoers could be dealt with quickly, removing God’s anger.

Sanhedrin 36a-b

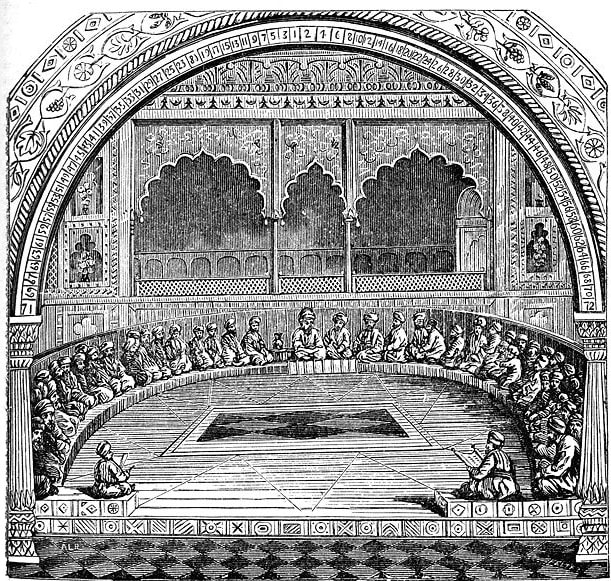

Which of the judges speaks up first during deliberations?

According to the Mishnah (32a) the eldest or greatest of the judges speaks first in all cases, aside from dinei nefashot – capital cases – where we begin “from the side” – we let others speak up first.

The Gemara on today’s daf brings Rav who reports that as a judge in the court of Rabbi [Yehuda HaNasi] he was the one who spoke up first. The Gemara questions why Rav would have been asked to offer his opinion first. Given that during Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi’s time the Sanhedrin had already stopped dealing with capital offenses it is clear the trials under discussion are ordinary cases, where Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi himself should have begun the discussion. In response Rava’s son Rabbah – and some say Rabbi Hillel the son of Rabbi Valles – explained that in the courtroom of Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi it was common practice that in all trials they began with one of the weaker, and less experienced judges.

The explanation for this appears connected with the continuation of the Gemara, where we find those same amoraim describing how unique a personality Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi was – that from the time of Moshe until Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi we do not find Torah scholarship and greatness (leadership and wealth) in a single person. Thus there was a serious concern lest Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi’s position be accepted without any dissent, were he to have spoken first.

Another explanation that is suggested is based on the fact that Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi’s courtroom was qualitatively different than others. As compiler and editor of the Mishnah, many of the discussions that took place there dealt with decisions that would establish halacha for future generations. As such, they were serious enough to be treated like capital cases rather than like simple ones.

Sanhedrin 37a-b

What should our attitude be towards sinners? And what hope of success must we have when working with them?

The Gemara on today’s daf quotes a passage from Shir HaShirim (4:3) “…your temples are like a pomegranate split open behind your veil,” which Reish Lakish interprets homiletically to mean that “even the emptiest among you are full of good deeds like a pomegranate [is full of seeds].”

Similarly, Rabbi Zeira quotes a passage in Sefer Bereshit (27:27) where Yitzhak smells Esav’s clothing that Yaakov was wearing, and concludes that they have the beautiful smell of the fields blessed by God. Rabbi Zeira interprets this pasuk homiletically to mean that even Jewish evildoers have outstanding qualities (according to the Maharsha, just as Yitzhak was able discern Yaakov’s good qualities even though he was disguised, similarly the good qualities of an evildoer may be hidden, but they are there).

In support of his interpretation, the Gemara relates the following story about Rabbi Zeira. In Rabbi Zeira’s neighborhood there was a group of troublemakers who Rabbi Zeira was always friendly with hoping that they would repent from their problematic ways, a position discouraged by the other Sages. Upon Rabbi Zeira’s death the troublemakers said: With the passing of harikha katin shakei – “the small one with burnt legs” – who will pray on our behalf? At that time, they repented and reformed their behavior.

The reference to Rabbi Zeira as harikha katin shakei refers to a story told about him following his emigration from Bavel to the Land of Israel, where he undertook a number of fasts. Enamored with the learning style in his new home, he fasted in order to forget the method of study in which he had been trained in the Diaspora. He also took upon himself a series of fasts so that he would merit avoiding the fires of Gehenna. To ensure his success, he would test himself in a hot oven, where his legs once became burned, and gained a nickname from that event.

Sanhedrin 38a-b

The Mishnah (37a) lists the warnings that the judges gave to witnesses who were about to testify in order to ensure that they will speak the truth in cases of dinei nefashot – capital cases. The judges point out the most basic difference between ordinary testimony and testimony in capital cases. While in money matters money that is taken unfairly can always be returned, when capital punishment is carried out unjustly “his blood and the blood of his descendants will be your responsibility forever.” The source for this idea is the passage that describes how when Kayin killed Hevel (see Bereshit 4:10) the Torah says that Hevel’s blood – demei, in the plural – was crying out to God.

The Mishnah follows this with the oft-quoted statement, that Man was created as a unique individual (as opposed to animals and plants, where the creation story indicates that many of each species were created at the same time) in order to teach that whoever destroys a single soul of Israel is considered as though he had destroyed a complete world; and whoever preserves a single soul of Israel, is considered as though he had preserved a complete world. Furthermore, the Mishnah continues, creation of Man also attests to the greatness of God, for when a human being strikes coins from a mold he will always create identical coins, while God created a single Man, yet all of His creations are unique.

The method used for making coins involved first creating blank circles of metal that were then stamped with a hammer blow.

It should be noted that although the text of our Mishnah reads “that whoever destroys a single soul of Israel is considered as though he had destroyed a complete world; and whoever preserves a single soul of Israel, is considered as though he had preserved a complete world,” alternative readings in manuscripts and other texts do not include the word “Israel” and teach simply “that whoever destroys a single soul is considered as though he had destroyed a complete world; and whoever preserves a single soul, is considered as though he had preserved a complete world.”

The Gemara on today’s daf develops these ideas, emphasizing the importance of the uniqueness of every individual, with Rabbi Meir, for example, teaching that we find three unique qualities in every person – their voice, their appearance and their thoughts.

Sanhedrin 39a-b

What relationships existed between the Sages and their non-Jewish contemporaries?

One example of a close relationship can be learned from the stories told of Rabban Gamliel of Yavneh, who was head of the Jewish community following the destruction of the Second Temple, and the Caesar – most likely one of the Caesars that followed Vespasian’s dynasty (perhaps Traianus) – whose interests included science, literature and the religious beliefs of other cultures.

The Gemara on today’s daf lists questions posed by the Caesar to Rabban Gamliel about issues of religion and science. For example, one challenge that was posed accused God of being a thief, since the Torah describes that he put Adam to sleep in order to steal the rib from which Eve was created (see Bereshit 2:21). Before Rabban Gamliel could respond, the Caesar’s daughter asked if she could share her thoughts on the matter. She asked her father to bring a military guard to investigate a robbery that had taken place in her home. When asked for details she told him that a thief had come in the night and taken a silver pitcher, leaving a golden one in its place. The Caesar’s response was that such thieves should visit more often. When she clarified that this is what God had done to Adam – exchanging a rib for Eve – her father suggested that in that case it could have been done openly. This time she responded by calling for a piece of raw meat and preparing it before him. Having seen it in its raw state, the Caesar found it unappetizing. Yet again his daughter pointed out that God did not want Adam to find Eve repulsive.

Another question posed by the Caesar to Rabban Gamliel related to a passage in Tehillim (147:4) that describes how God counts the stars. The Caesar found this claim unimpressive, arguing that he, too, could count the stars. Rabban Gamliel took a number of quinces and put them in a sieve that he set spinning. When the Caesar could not keep track of them, Rabban Gamliel argued that the heavens work in a similar fashion.

Already in ancient times, astronomers attempted to map the heavens and count the visible stars. According to their count, less than 2000 stars were visible in the Northern hemisphere. The traditional view of the Rabbinic Sages was that there were many more stars, and that their number could not be counted. With modern telescopes we now know that there are many millions of stars in the heavens and that it is impossible to establish how many there are.

Sanhedrin 40a-b

Since Jewish law gives almost no credence to circumstantial evidence and to proofs based on supposition and assumptions, direct eyewitness testimony becomes essential. This is especially clear when dealing with dinei nefashot – capital cases – since in such cases Jewish law will not even accept admission on the part of the accused. Thus, it is only through the testimony of witnesses that we can establish what happened in a given situation and how it took place.

In previous chapters of Masechet Sanhedrin we learned what type of person could or could not testify, removing relatives and untrustworthy individuals from entering the courtroom as witnesses. The fifth perek of Masechet Sanhedrin, which begins on today’s daf focuses on the methods used by the courts to question the witnesses in order to verify the truthfulness and accuracy of their testimony.

There are two basic stages in examining the witnesses’ testimony. First it is necessary to establish the basic information: the time and the place of the incident, as well as the basic question of what happened. Only after these questions have been clarified does the court delve into details of what happened and how it occurred.

According to the Mishnah, there are seven of the first type of questions, which are called chakirot (searching queries), and include questions about time and place. There are additional questions that deal with whether the witnesses recognize the victim and/or the accused and whether they warned the accused that he would be liable for his actions (according to Jewish law, no punishment can be given unless the accused had been warned of the consequences of his actions). It is not clear whether these questions are chakirot or if they are the second type of question, called bedikot (examinations). The Me’iri offers an additional category that he calls derishot (clarifying questions) that have the same level of severity as chakirot.

Sanhedrin 41a-b

The Mishnah (40a) taught that witnesses are questioned by the court by means of both chakirot (searching queries), and bedikot (examinations). There are seven specific questions under the category of chakirot that deal with basic questions of time and place and if a witness cannot answer any one of the questions of chakirot, his testimony will not be accepted. Regarding bedikot the Mishnah teaches that the judges can ask whatever they want, and if the witnesses cannot answer questions of bedikot, their testimony still stands. A story is related that Ben Azzai once demanded information about the stems of figs.

The Gemara on today’s daf presents an attempt by Rami bar Hama to connect the figs to the trial itself (e.g. the man was accused of picking them on Shabbat or of using them as a murder weapon), but it concludes with the words of Rav Yosef who says that Ben Zakkai held a unique position that bedikot questions were the equivalent of chakirot questions, which allowed him to ask penetrating questions that others would not have used.

Who is Ben Zakkai?

The Gemara is reluctant to identify him with the great tanna, Rabban Yochanan ben Zakkai, since the story in the Mishnah places him as a member of the Sanhedrin dealing with capital cases, while we have a tradition that of the 120 years of his life Rabban Yochanan ben Zakkai spent the first 40 as a businessman, the next 40 as a student and the final 40 as a teacher. Furthermore we know that the Sanhedrin moved from its location on the Temple Mount and ceased to try capital cases 40 years before the destruction (see Rosh Hashana 31b), yet Rabban Yochanan ben Zakkai was active as a teacher and leader of the Jewish community after the destruction of the Second Temple. The Gemara concludes that he must have presented his idea of asking questions of bedikot that include such detailed information while he was still a student and was called simply Ben Zakkai.

In addition to his monumental translation and commentary on the Talmud, Rabbi Steinsaltz has authored dozens of books and hundreds of articles on a variety of topics, both Jewish and secular. For more information about Rabbi Steinsaltz’s groundbreaking work in Jewish education, visit www.steinsaltz.org or contact the Aleph Society at 212-840-1166.

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.