The Coming Week’s Daf Yomi by Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz

This essay is based upon the insights and chidushim (original ideas) of Talmudic scholar Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, as published in the Hebrew version of the Steinsaltz Edition of the Talmud.

Bava Batra 49a-b

According to Jewish law, what are some of the mutual responsibilities of husbands and wives?

This question is discussed by the Gemara in response to the Mishnah‘s teaching (see daf 42a) that ba’al be-nikhsei ishto – a husband working his wife’s property – will not gain a chazaka on the field. Since the husband has legitimate reason to be on the field – he has rights to the produce – there is no reason for his wife to complain about his presence there, so his being there cannot support a claim that the field had been purchased by him.

The Gemara objects that this is obvious, and need not be taught, since everyone knows that a husband has rights to the produce in his wife’s field. In response the Gemara suggests that this is talking about a case where the husband says din u-devarim ein li be-nechasyich – I have no claim to your property – renouncing his right to the produce that ordinarily belongs to him by law. Thus, the Mishnah is teaching that even in such a case, where the husband has no right to be in his wife’s field, still he cannot claim to have a chazaka if he has spent three years in the field, since it is likely that his wife did not object to him being in the field even without a legal right to be there.

In explaining how the husband may lose his rights to the produce in his wife’s field, the Gemara quotes Rav Huna in the name of Rav who rules that a woman can say to her husband eini nizonet ve-eini osah – you do not have to feed me, and I will not turn over my earnings to you.

The Gemara in Masechet Ketubot explains that the mutual responsibilities between husband and wife established by the Sages offer a measure of equality between them. The Ritva understands that according to Rav Huna the parallel obligations of mezonot and ma’aseh yadayim (food for the wife in exchange for her earnings) were established for the wife’s benefit, since the husband must provide full support even if she earns very little. It is for this reason that she can choose to reject the Rabbinic enactment if she chooses.

Bava Batra 50a-b

In our Gemara, Rabbi Yossi bar Chanina teaches that a Rabbinic enactment was made in Usha establishing that if a woman sold her nichsei melug (possessions that remain the property of the wife during marriage), in the event that she passes away before her husband, he can collect the land from the purchaser, since he has a primary claim to it.

What are takanot Usha?

According to the Gemara in Masechet Rosh Hashana (31a), at the time of the destruction of the Temple, as the Jewish people were sent into exile, God joined them by removing His presence from the Temple in a series of stages. In a parallel move, the Sanhedrin gradually removed itself from its offices on the Temple Mount, as well, making its way to the Galilee (see map), where most of the remaining Jews were to live under Roman rule.

The Sanhedrin’s first stop after leaving Jerusalem was the city of Yavneh, which was established as a center of Torah study by Rabban Yochanan ben Zakkai, and became most famous under the direction of Rabban Gamliel of Yavneh. Throughout its continuing travels, the Sanhedrin was headed by descendants of the family of Hillel.

It appears that the Sanhedrin was moved to Usha in the aftermath of the Bar-Kochba revolt, where a series of Rabbinic enactments – called takkanot Usha – were established. Under the leadership of Rabbi Shimon ben Gamliel there was an unsuccessful attempt to return the Sanhedrin to Yavneh, but due to the overwhelming devastation in the southern part of the country, they returned to the Galilee, first to Usha and then to Shefaram.

Takanot Usha deal mainly with establishing the norms of monetary relationships within families. While these enactments were not included in the Mishnah, they were known to the amoraim based on oral traditions.

Bava Batra 51a-b

As we have learned, in order to transfer property from one person to another, a kinyan must take place. A kinyan is an act that indicates a final decision on the part of the owner to sell and the purchaser to buy.

The Gemara on today’s daf discusses a kinyan that is done by means of a shtar – a contract or legal document. Rav Hamnuna quotes a baraita that teaches that a shtar is valid if it was written on paper or on clay, even if it is not worth a prutah – a small sum of money. Tosafot point out that there is really no need to teach that the shtar does not have to have inherent value, since it is what is written in the document that creates the kinyan; property transfer based on a shtar is not based on chalipin – a trade of two things with value. Some rishonim follow the Ramban in saying that we may have thought that in order for a shtar to be a significant document it must have some minimal value.

With regard to a shtar that is written on clay, Tosafot point out that other sources appear to forbid writing a contract on clay, since soft clay can easily be erased and the terms of the contract changed after it is signed. Among the answers that are suggested are:

- That this baraita follows the opinion of Rabbi Eliezer who believes that the kinyan takes effect based on the witnesses who see the shtar transferred between the two parties, rather than being based on what is written in it (see Tosafot and the Ritva)

- That this case is one where the clay was hard and the letters were chiseled into it, so the tablet could not be erased (see the Rashba)

- That the prohibition against using clay is only when the shtar was needed to act as proof of the transaction. In the event that it was needed only to create the transaction at the beginning of the process, it did not need to be a permanent record.

Bava Batra 52a-b

As we learned in the Mishnah (daf 42a) the term chazaka has two different meanings. While most of our perek has dealt with chazaka as an act that supports a claim of ownership, i.e. living or working a piece of land for three years will support a man’s claim that he had purchased the land, there is another type of chazaka, as well. A chazaka can also mean a formal act that shows that a person controls the land, which will serve as an act of kinyan – of taking possession of the land.

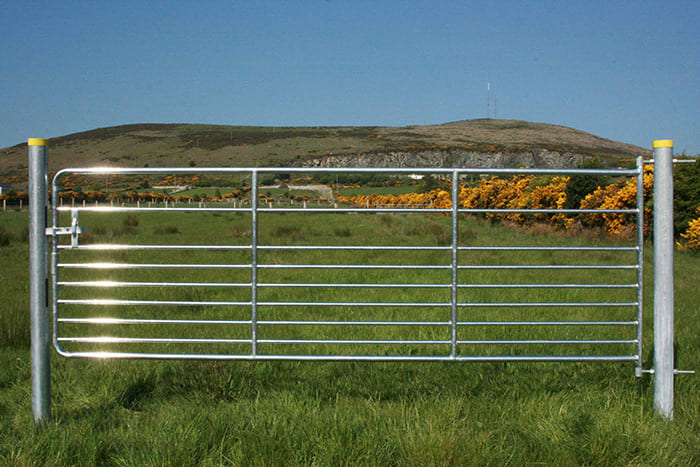

In the case where the chazaka will serve as an act of acquisition, for example, where someone gives a present to another, then the chazaka of na’al, gadar u-faratz will be effective. That is to say, if the recipient of the present locked the door, put up a fence, or performed any other action that exhibited ownership, such a chazaka will effect ownership.

In defining the case of na’al – locking the door – the Rashbam explains it does not simply mean locking an existing door, rather that the new owner establishes a door in a space that did not have one previously, or minimally placing a lock in a door that did not have one before. The Ramah disagrees, claiming that according to Rav Hai Gaon even closing the door – which is referred to by the term ne’ilah by the Rabbinic Sages – would be enough to complete the kinyan, since it changes the inside into a “closed area” at least for that particular moment, which is enough to exhibit ownership. The Ramah goes one step further, suggesting that opening a door that had been locked can also be seen as a sign of ownership, since it is similar to someone who breaks down the gate around a field. According to him, both of these exhibit control over the property.

Bava Batra 53a-b

As we learned on yesterday’s daf when dealing with a chazaka that serves as an act of acquisition, then the chazaka of na’al, gadar u-faratz will be effective. That is to say, if the recipient of the land locked the door, put up a fence, or performed any other action that exhibited ownership, such a chazaka will effect ownership.

Rav Nachman quotes Rabbah bar Avuha on today’s daf as teaching that if someone builds a significant structure (a paltarin, or castle), on land owned by a deceased convert who has no heirs – i.e. ownerless land – but someone else comes and puts doors into the structure, it is the second person who has successfully claimed ownership. He, after all, is the one who has performed the necessary na’al, gadar u-faratz. The Gemara explains that we see the act of the first person as merely being “moving around the bricks.” Since the house is not yet complete, the act of putting bricks together, and even completing walls, is not sufficiently significant to create a chazaka.

The Ri”d explains that since he has not performed the necessary na’al, gadar u-faratz, he has not successfully laid claim to the land. Therefore it is as though he has built on his friend’s property without permission, which does not give him any rights to the land. The Ramah argues that this must be a case where the bricks did not belong to the first builder – perhaps he found them on the field. Were they his own bricks, then when the second person comes and places a door in the unfinished house, he is placing it on someone else’s property, and the first person can remove the door and replace it with his own – thereby claiming the field. Tosafot explain that even though an almost completed building can serve a valuable purpose, e.g. as protection from the rain, as long as there are no doors it cannot be considered a dwelling place, which allows us to view it merely as a structure that has ruined the farmland or pasture. It will not be viewed as a constructive edifice – which would allow him to lay claim to the property – until it is complete.

Bava Batra 54a-b

The Gemara has been discussing a case where someone takes possession of land by performing an act that expresses ownership – the chazaka of na’al, gadar u-faratz – if the recipient of the land locked the door, or put up a fence.

Our Gemara adds another action that is considered to be significant – if the person digs a hole or furrow in the ground. This act is significantly different than the others, since it relates to a specific place on the field and not to the fence that surrounds the entire field. Therefore, the Gemara on our daf (=page) brings a difference of opinion with regard to the effectiveness of digging in the ground. Can the entire field be claimed by means of this action? Rav Huna quotes Rav as saying that as long as the field is enclosed by a fence, a single shovel in the ground is a claim on the entire field. Shmuel rules that it is only significant in the place where the hole was dug.

The commentaries point out that this argument only applies to a case where it is an ownerless field that is being claimed – e.g. the case of the field of a convert who passed away with no living heirs. Were this a normal case with a seller and a buyer, the da’at makneh – the intent on the part of the seller to transfer ownership – will play a role in giving significance to a symbolic act and allow transfer of the entire field.

The Gemara appears to accept Rav’s opinion that if the field is enclosed, a symbolic act of digging in the ground is a claim to the entire field.

What if the field does not have a fence around it? Rav Papa rules that it claims the amount that the ox driver ordinarily plows and then returns.

Several different opinions are offered in explanation to this ruling:

- The Rashbam understands that once a person digs two furrows on the side of the field, the entire field is claimed by him.

- The Rashba and Ritva explain that it is talking about a square the length and width of the normal furrow.

Bava Batra 55a-b

It is useful to divide agricultural fields for a variety of different reasons. Traditionally, fields are not separated only by fences, but also by other types of boundaries.

The Gemara on our daf discusses Rabbi Yochanan‘s approach to two types of divisions – metzer (a pathway) and chatzav (squill, a type of plant planted in order to separate between fields). According to Rav Assi, Rabbi Yochanan believes that simple separations like these would divide a field in the case of nikhsei ha-ger (when someone claims the field of a convert who passed away with no living heirs – see yesterday’s daf) but not in cases of pe’ah (leaving a corner of the produce of one’s field for the poor) or tumah (if someone walked through fields and is not sure whether he entered a field where there was an issue of ritual defilement, like a dead body, and became tamei or not). When Ravin came from Israel, he quoted Rabbi Yochanan as ruling that metzer and chatzav would act as a separation between fields even for pe’ah and tumah.

The point of disagreement is, apparently, based on whether these types of separations that are neither natural boundaries (like a river) nor are they clearly made for the purpose of dividing the fields (like a fence), should be recognized as an official separation. According to Rav Assi, we will accept it as such only in cases that are of Rabbinic concern – e.g. taking possession of nikhsei ha-ger. In cases where the concern is Biblical – e.g. pe’ah and tumah – we cannot accept these as divisions. Ravin understands that metzer and hatzav are acceptable boundaries in all cases.

Chatzav, Urginea maritima or squill, is a plant with a large bulb, which produces an abundance of green leaves during the winter months and dries up in the summer. At the end of every summer the chatzav sprouts tall stalks topped by small, white flowers. Both the leaves and the bulb contain poisons, which keep animals from eating them. The dried bulbs were traditionally used in the production of medicines. The chatzav has a long root system. Because of its sturdiness and its ability to grow again every year, during ancient times it was popularly used to demarcate the boundaries of fields, a role that it still plays in traditional villages in Israel.

In addition to his monumental translation and commentary on the Talmud, Rabbi Steinsaltz has authored dozens of books and hundreds of articles on a variety of topics, both Jewish and secular. For more information about Rabbi Steinsaltz’s groundbreaking work in Jewish education, visit www.steinsaltz.org or contact the Aleph Society at 212-840-1166.

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.