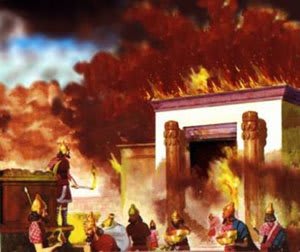

Although the Temple in Yerushalayim has been desolate for almost two thousand years, its memory is very much alive for the Jewish people. We remember the Temple in our daily prayers, in our periodic fasts including that of Tisha b’Av starting Motzei Shabbat, and also in various customs which continue the mourning over the loss of the Sanctuary throughout the year, and especially on happy occasions.

For example, when we build a house we leave a little bit unfinished; when we make a wedding the groom breaks a glass (SA OC 560). These customs emphasize that even when we have moments of special joy, our simcha is not complete as long as the Temple is in ruins. Remembering the Temple at happy times is also important because the exhilaration of joy is liable to make us forgot our mourning even if we are normally conscious of it.

Rebbe Yochanan ben Zakkai enacted certain decrees immediately following the destruction itself. These decrees displayed remarkable foresight, because at that time Rebbe Yochanan actually faced a double challenge. While the disappearance of the Temple created a need to commemorate it, so that future generations would not forget the importance of the Beit HaMikdash, there was paradoxically an opposite challenge as well: to help people forget the Temple.

For more than a thousand years, the Jewish people had not been without a Sanctuary, except for short periods such as the beginning of the Babylonian exile when there was a Divine promise limiting the absence to seventy years. Profound despair gripped the people, as many Jews did not believe that the Jewish religion or even the Jewish nation could survive without the Temple. (See Bava Batra 60b.)

Striking a balance between the need of his generation for consolation and the need of future generations for perpetuation, Rebbe Yochanan and the other Sages instituted two distinct kinds of decrees which could call zekher lemikdash and zekher lechurban: commemoration of the Mikdash and commemoration of its destruction.

The first kind of decree introduced into universal halakha customs that were formerly only in the Temple, demonstrating that life goes on even without the Beit HaMikdash. For instance, previously the lulav was waved on chol hamoed only in the Temple; Rebbe Yochanan ben Zakkai instituted that it should be taken throughout the holiday everywhere. (Mishna Rosh HaShana 4:3.)

The second kind of decree came to recall the Temple’s absence. For instance, the new year’s grain crop used to become permissible when the omer offering was brought. But when there is no Temple and no offering, it becomes permissible immediately on the day following Pesach. Rebbe Yochanan instituted that it was necessary to wait until the end of the day, to demonstrate that we are still waiting for the Temple to be built. (Mishna Menachot 10:5.)

Together, the various customs which related to the destruction create a balance in Jewish life: we recognize that Torah observance goes on even without a Temple, but we remind ourselves that our observance is far from complete.

Rabbi Asher Meir is the author of the book Meaning in Mitzvot, distributed by Feldheim. The book provides insights into the inner meaning of our daily practices, following the order of the 221 chapters of the Kitzur Shulchan Aruch.

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.