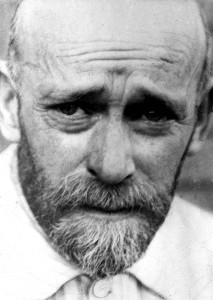

(PAP/CAF Archiwum)

He was not religious, but he became a saint. He did not go to synagogue, and knew no Hebrew, but he was a martyr. In a world where men changed themselves willingly into beasts, he dedicated his life to saving children.

He was Dr. Janusz Korczak (1878-1942), physician, sociologist, psychologist, father, author, poet, and a man who gave his career, his life, to working with orphan children. In these dog days of summer, with the flames of History licking at the Holy Temple, I remember him. Born Henryk Godszmit in Poland in 1878 (I, too, am part Polish; it is not a legacy of which I have ever really been proud—the Poles, if they did not invent anti-semitism, certainly refined and contributed to it), he introduced the first progressive orphanages for both Catholic and Jewish children into Poland, founded the first children’s newspaper, and testified on behalf of children in juvenile courts. He wrote a novel, King Matt the First (1922), about a child-king who dreamt of a children’s crusade that would eliminate evil from the world. He organized his own orphanages to resemble “children’s republics,” in which his young charges took on a portion of self-government.

And he lived, and died, with his orphans. When World War II began, he might have escaped from Nazi-occupied Poland, but he chose to stay. A hero of World War I, he dressed himself in his old uniform and went to the Nazi authorities demand more food rations for his orphans. He was beaten and thrown into a cell. Released, he returned to his children, there in the Warsaw Ghetto, determined to survive and flourish, for however long they could.

He described himself as a “sculptor of a child’s soul,” and understood how children need, require, yearn for, a sense of order. In Betty Lifton’s words, “He would tell a misbehaving child, ‘ I’m angry at you till lunchtime or supper.’ …The child would understand that he was being punished, but also that there was a time limit, after which would be forgiven and could begin anew.” I wonder how many children there are, out there in the World, who would benefit from such a loving regimen.

Finally, there came the end, to which nearly all the young members of Korczak’s Children’s Republic were sacrificed: the death camp of Treblinka, where flowers were planted along the tracks, and where the hands of a fake painted station-clock pointed forever to 3. About four thousand children and their teachers and nurses were deported from Warsaw that day, brutally escorted by the Jewish Ghetto Police and the Nazi soldiers and SS. Korczak’s group was one-hundred-ninety-two children and ten adults, with himself at the head. He had been offered a last-minute chance to escape, but refused: he wished to stay with his children.

Korczak was at the head of this little army, the tattered remnants of the generations of moral soldiers he had raised in his children’s republic. He held five-year-old Romcia in one arm, and perhaps Szymonek Jakubowicz, to whom he had dedicated the story of Planet Ro, in the other.

Stefa (his head nurse) followed a little way back with the nine- to twelve-year-olds. There were Giena, with sad, dark eyes like her mother’s…. There were Jakub, who wrote the poem about Moses; Leon with his polished wooden box; Mietek with his dead brother’s prayer book; and Abus, who had stayed too long on the toilet. …

The sidewalks were packed with people from neighboring houses, who were required to stand in front of their homes when an Aktion was taking place. As the children followed Korczak away from the orphanage, one of the teachers started singing a marching song, and everyone joined in: “Though the storm howls around us, let us keep our heads high.”

…Korczak headed the first section of children and Stefa the second. Unlike the usual chaotic mass of people shrieking hysterically as they were prodded along with whips, the orphans walked in rows of four with quiet dignity. “I shall never forget this scene as long as I live,” [Nahum Remba wrote; he was a Judenrat official, who had offered to save Korczak’s life, but without the children’s; Korczak had refused] “This was no march to the train cars, but rather a mute protest against this murderous regime…a procession the like of which no human eye has ever witnessed.”

As Korczak led his children calmly toward the cattle cars, the Jewish police cordoning off a path for them saluted instrinctively. Remba burst into tears when the Germans asked who that man was. A wail went up from those still left on the square. Korczak walked, head held high, holding a child by each hand, his eyes staring straight ahead with his characteristic gaze, as if seeing something far away

(Lifton, 1988, pp. 340; 344-5).

This Tisha B’Av, I turn from other Jewish catastrophes to this one: a small teardrop in an immense ocean of tragedy, perhaps—and there are other children, thousands, perhaps millions, suffering as I write, out there in the World; how can we save those children, in memory of Dr. Janusz Korczak?

The question stands….

(Excerpts from Betty Jean Lifton, The King of Children: A Biography of Janusz Korczak. NY: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1988.)

David Hartley Mark blogs at http://deitychaser.blogspot.com.

Want to hear more about heroes? Join us for our Tisha B’Av webcast about heroes in the time of horror.

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.