Maintaining Values on the Job – No Matter What

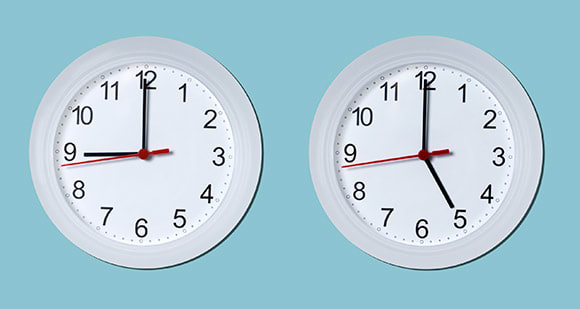

Wholly apart from the serious halachic (commanded) infractions not dealt with here, the work environment can adversely affect one’s values and attitudes. Some individuals relegate their work life to insignificance, where their attitude is “What I do from 9 to 5 is nothing. I live for Shabbat…for my shiur.”

While at first glance, this may seem to be a praiseworthy attitude since one recognizes that life’s primary purpose is avodat Hashem, eventually this kind of thinking can be very destructive. If one thinks that what he does eight to ten hours a day is worthless and not a way of connecting to God, that could easily destroy him from within. How can a person spend so many hours a day in worthless pursuits? Indeed, this kind of thinking can lead to depression, despondency and hopelessness. There is also the opposite problem— that one gets so invested in professionalism as the mark of his importance that he loses his sense of priorities in life.

Thus, how we relate to our work involves a very delicate balance. We must place our work lives in proper perspective—our jobs are essentially vehicles to support ourselves and raise Jewish families; means to give tzedakah (charity) and strengthen Torah; opportunities for productivity and tikkun olam (improvement of society); and enablers of kiddush Hashem and gemilut chesed. Our jobs are useful, important and significant, but not ends in themselves.

Yet another pernicious problem is simply the lack of time and energy needed to think. All human beings need time to reflect, and bnei and bnot Torah, children of Torah, in particular need time to be able to answer questions such as where are their lives going and why.

Yet we are on treadmills all the time. We are part of the rat race and we begin to feel like beleague red rats. After all, take the typical lawyer in a major Wall Street law firm who might work 60-65 hours a week. Why isn’t such a heavy work schedule slavery? A slavery that asserts its mastery not just over our time but over our hearts, our souls, our concentration and our kochot hanefesh (energies).

If, as Thomas Paine remarked, “The price of [political] liberty is eternal vigilance,” this is even truer for spiritual liberty and freedom. It is so easy to lose sight of life’s ultimate purpose when we are so preoccupied with our daily routine. Indeed, according to a survey, the amount of time that husbands and wives spend talking to each other about matters other than housekeeping is less than 20 minutes per week.

Look at what the work culture has done to us. In contrast to the prototypical ba’al habayit (head of the household) of the Rambam who earns enough for his daily bread in three hours and can utilize the remaining nine hours of daylight for Torah study, 8 our work seems to have taken over our entire lives. In short, we are slaves; we are slaves both to our work and to the negative emotions that work engenders within us including envy, possessiveness, materialism, arrogance and the like.

Keeping an Eye on the Ultimate Destination

A modern adaptation of a parable by the Dubnow Maggid brings out this point forcefully. The story involves an obsessive-compulsive individual who always had to be fully prepared for whatever life threw his way. When he was making his first trip to Israel, he was told there would be a seven-hour stopover in France. He decided that he would prepare for the trip by learning French so that he would be able to order a Coke in the proper language.

He studied hard for an entire year. By the time he got to the airport, he had mastered the language. He was proud of himself and he impressed a lot of people. But seven hours later, when he got back on the plane, he realized with a sickening feeling that he never bothered to learn Hebrew. He was so preoccupied with the stopover that he never gave thought to the ultimate destination.

This world is a prozdor, an entry way and a hallway to the World to Come. There are certain skills necessary for navigating the hallway: we have to make a living, learn how to drive, etc. but if we put all of our energies into navigating this world, and never give thought to the ultimate currency we take with us to the Olam Haemet (the World of Truth), we are as misguided and short-sighted as that gentleman. It would do us well to remember that nobody ever leaves this world wishing he had made one more big deal.

But the dangers go beyond the simple inability to think. There is a subtle, and not-so-subtle, reprogramming of thought that occurs as well. Rabbeinu Yonah [9] writes that a major component of how we are judged in the eyes of Hashem is what we truly regard as important in the innermost depths of our hearts. What is it that we really admire?

Very often because of the all-consuming energy we have to put into our work, we do mitzvot perfunctorily. Theoretically, every Shabbat must be a new Shabbat, every tefillah, a renewed conversation with the Creator, every holiday, a unique encounter with the Divine. But drained of our energies and buffeted by competing and inconsistent versions of the “good life,” our spiritual selves often atrophy into something arid, mechanical, unfeeling and superficial.

The problem of stagnation is, of course, a general problem in the life of the religious Jew. The prophets identified this as mitzvat anashim melumadah [10], doing mitzvot habitually. And yet, while this problem is relevant to every Jew and not just the working population, the lack of time, energy and yishuv hada’at (peace of mind) make the working person exceptionally prone to the notion of not growing in avodat Hashem. The Torah compares a person to a tree. Just as a tree grows when it is rooted in the ground and receives adequate sun, water and nutrients, a person can grow spiritually if he receives adequate nourishment for his soul. If our religion doesn’t provide us with adequate nourishment, we die within. And this deterioration can happen very slowly. A tree can be dead while all the leaves are still green and intact. Similarly, a person can spiritually die even while appearing vibrant and alive. And there is perhaps no greater tragedy than this.

Making Spirituality Vibrant and Personal

How can we infuse our work days with spirituality? We must keep a life-line to a rebbe, a posek, a yeshivah, a shul and a kehillah. It is important not to be alone, to surround ourselves with friends who have spiritual aspirations and with people who consciously strive to work on themselves spiritually and grow in avodat Hashem.

For men, it’s important to daven with a minyan three times a day. For men and women, it is especially important to ensure that Shabbat and Yom Tov are seen not just as days of rest (though that has a place too) but as days of sanctity, love and joy, days dedicated to spending time with family, to engaging in fervent and meaningful prayer as well as challenging Torah study. For it is these days above all that can provide the fuel that will continue to warm the heart and inspire the soul throughout the work week.

Virtually every working environment needs the equivalent of a neon sign that says, “Proceed with caution,” and yet amidst the risks, there are many positive opportunities for growth. In Hilchot Deot (3:3), the Rambam lays down a very fundamental idea based on the verse in Proverbs (3:6) “Bechal derachecha da’eihu, Know God in all your ways.” Da’eihu is derived from the verb da’at, which refers to more than knowing; it implies an intimate sense of being connected. The Rambam explains that if one works with the intention to earn money to serve Hashem, give tzedakah and support one’s family, then one’s working hours are not just a vehicle for those noble goals but actually constitute avodat Hashem. I would suggest that the same way before one performs a mitzvah, one says “Hineni muchan umezuman, I am readying myself,” perhaps every day one should start off with a silent or verbalized tefillah to Hashem, that “what I’m going to do for the next eight hours is with the intention of serving You.” If you start off with that orientation, then your entire workday constitutes avodat Hashem.

The Chofetz Chaim used to explain that when Hashem told Moshe at the burning bush, “Take off your shoes because the place where you are standing is holy,” He was speaking to all of us—that no matter where we live or what we do, there is the potential for holiness and sanctification. It is incumbent upon us to find it. 12

Notes

1. See Rav Dov Katz, Tenuat HaMusar, vol. 1, p. 352.

2. One exception is medicine where Shabbat issues continue to be of major importance.

3. See, e.g. Michael J. Broyde, The Pursuit of Justice and Jewish Law (Hoboken: Ktav Publishing House, 1996), and the many books by Dr. Fred Rosner on medical ethics.

4. See generally Shulchan Aruch Choshen Mishpat228 and 231.

5. See also the powerful words of Rabbeinu Moshe of Coucy in Sefer Mitzvot Gadol, Mitzvot Aseh74, where he states that Jews who behave as thieves, cheats and liars towards non-Jews prolong the galut and cast aspersions, as it were, on the Ribbono Shel Olam who has chosen such evil-doers as His people.

6. The classic written work on these laws is Sefer Chofetz Chaim and the most popular English adaptation is Rabbi Zelig Pliskin’s Guard Your Tongue. The Chofetz Chaim Heritage Foundation also operates a halachic hotline where people can call to consult with a rav. It should be noted that there may be other prohibitions besides lashon hara in attempting to lure away a competitor’s customers. See Choshen Mishpat156 and 237.

7. See commentary of the Ramban, Genesis 22:1.

8. See Rambam, Hilchot Talmud Torah 1:12. I do not intend to suggest that the Rambam’s picture of a ba’al habayit was ever historically accurate— indeed, Rambam’s own schedule as court physician in Cairo shows that it was not—but it does represent an idealized picture of productive work being placed in a proper perspective.

9. Proverbs 27:21, Commentary of Rabbeinu Yonah.

10. Isaiah 29:13.

11. See Yoma 86a and Rambam, Hilchot Yesodei HaTorah 5:11.

12. See Chofetz Chaim al HaTorah, Shemot 3:5.

Rabbi Breitowitz is the rabbi of the Woodside Synagogue in Silver Spring, Maryland and an associate professor of law at the University of Maryland. This article is an abridgement of a speech given at a young professionals’ group.

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.