The first question most people asked me when I told them I was moving to Eretz Yisrael was usually, “have you lost your mind?”

This was generally followed by a question related to economics and finances, something to the effect of, “do you have a job lined up over there?” or “don’t you know parnassah is much tougher there?”

If the conversation persisted further, one of the next questions was inevitably “do you know where you’re going to live?” And in many ways, this was one of the toughest challenges of the Pre-aliyah experience: picking the right community for my family.

Living in the city was out for us: too expensive, too loud, and not enough trees and fresh air. But beyond trying to find a place with good schools, we also had to try and find a community that would suit our spiritual needs. We wanted a very strong Torah community but not one that was too rigid or too Anglo. And then reality set in and as it seemed there would be no perfect fit, it was just time to pick a place that wasn’t an awful commute and to rent an apartment already.

So we ended up in a very mixed community with a bunch of haredi families, many dati leumi families, and a few traditional ones as well. We found a place with enough Anglos to connect with but not too many that we’d never learn Hebrew. As they say, the rest is history.

One of the interesting results of this is the make up of my regular minyan which includes men with all sorts of head-coverings: big kippahs, small kippahs, velvet kippahs, Shabbos hats, streimels, and even a turban or two. But in spite of the differences on the outside and even the nussach (there were Ashkenazim, Temanim, Sephardim, and Hassidim), no one cared too much to talk politics and the regular mitpallelim were are united in our love of tefillah and Torah.

And then something interesting happened. As I was new to the community, I had no idea that a great Yerushalmi Rebbe came at the end of each summer for a Shabbos with a few dozen of his talmidim. In general it was leibedig to have a some extra bochurim around and davening in the presence of The Rebbe himself was inspiring. All in all he brought about thirty hasidim from Yerushalayim and it was a great aliyah for the kehillah.

Until a cousin of a guy who davens at our shul who had come for Shabbat decided to start a makhloket. I’m not sure how it began or who spoke first, but in short something was said about his army uniform and he made a comment about “draft-dodging.” This lead to a few not-nice statements about religious soldiers and Haredim as a whole and before you knew it there was a shouting match outside of the shul following mincha.

A few people ran to grab me to intervene. When I asked why, I was told, “you’re a psychiatrist which means you know how to calm people down.” It sounded like a good enough reason to take achrayis, but before you knew it the crowd was dispersed and everyone had headed their separate ways for seudah shlishit.

Given that we had a real-deal Rebbe handy and making his seudah shlishit near the shul, I joined my friend Shimon to find out what the Rebbe thought of this makhloket. We found him singing niggunim with the older Hassidim at a table he’d schlepped along from Yerushalayim. We approached and stood by the side until—perhaps to the surprise of his Hassidim—he offered us the precious seats next to him.

The Rebbe asked us a rhetorical question, “Do you know how special this table is?” Clearly we didn’t but for him to take it apart and bring it out of the city and then to rebuild it before Shabbat suggested that it must have a certain mailah to it. “This table belonged to a Rebbe who lived near my father who refused to sleep for over 20 years. Every day he’d learn Torah at this table until the point of exhaustion and his only naps during those decades were with his head on this table. It’s a beautiful table too so my father purchased it from his family after the Rebbe was niftar and now I can’t go without its kedusha.”

After a few more niggunim, my friend Shimon decided to ask the Rebbe our question, “Rebbe it’s sad that Jews are fighting. Even here in a religious community you have Jews arguing with other Jews about the army, about learning in yeshivah, it’s terrible. There’s no achdut.”

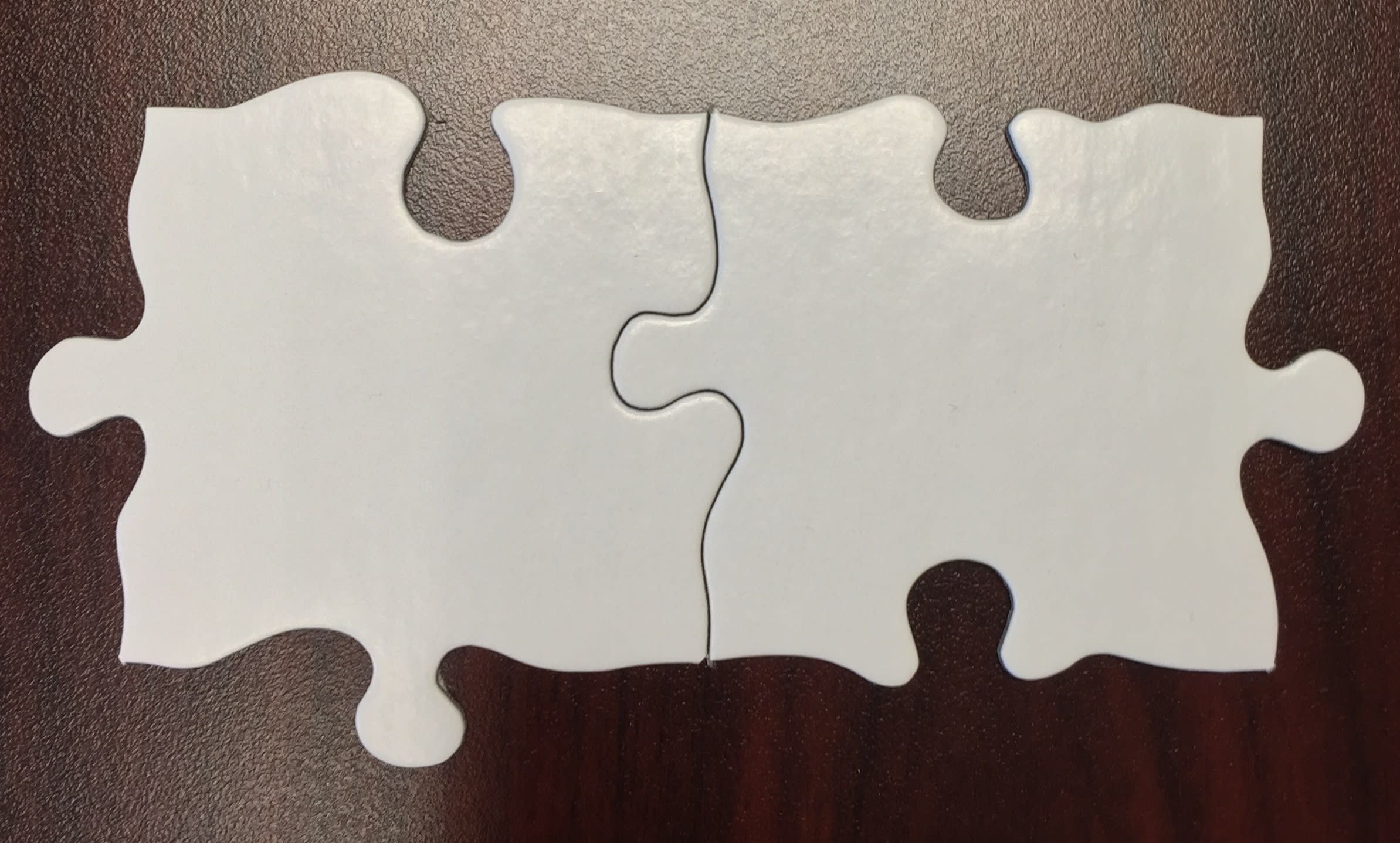

The Rebbe smiled and said, “We’re Ish Echad B’Lev Echad (one person with one heart). That means we’re a single guf! Do you think that the fingers get along with the eyes and that the nose doesn’t wonder what’s going on with the stomach? Sometimes the hands look down at the feet and say, ‘All you ever do is walk away, you never carry your weight.’ And then there’s the ears who say to the mouth, ‘you only chatter, you don’t listen to a single word.’ Even though we may look completely different from one another and have very different jobs sometimes, we need each other to function. We say every single day in the bracha of Asher Yatzar that it’s impossible to exist without even a single one of our 613 parts.”

I was too mesmerized to speak but Shimon smiled and said, “We are a single guf even if we don’t recognize it. This is the beauty of Am Yisrael, Rebbe! This is the beauty of the tefillah on Rosh Hashanah, Ve’asu lachem agudah echat (make yourself a united group). We are davening that even though we all look different that Hashem will wrap us all together and carry us across the finish line to geulah.”

The Rebbe smiled back and answered him, “Exactly. That is such a beautiful connection that I might even use it myself this Rosh Hashanah.”

We smiled and sang together. I didn’t know the tunes but they were worth learning. In time it became close to maariv and more and more people came back to shul to sit around the Rebbe’s table. Looking around there were people with all sorts of hats, beards, and hair-coverings singing along together. Nothing could bring Klal Yisrael together like a few good nigguns and nothing could be more important that achdut at this time of year. Luckily I’d have some good thoughts to keep me going during the Rosh Hashanah amidah.

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.