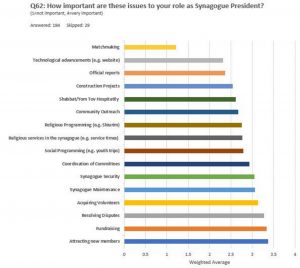

A place of prayer, learning and social gathering, the synagogue is the nucleus of Orthodox life. However, despite its acknowledged centrality, many congregations struggle to find volunteers to aid in its daily maintenance. Take it from one of the most generous volunteers that our community has: the synagogue president. Charged with the administration and maintenance of the synagogue, the president spends hours on a weekly basis dealing with issues relating to the synagogue. This is often in addition to a full-time job. In the summer of 2017, a survey was distributed to Orthodox synagogue presidents across North America, with the aid of the Orthodox Union, to better understand the role that synagogue presidents play within our communities. 223 presidents generously responded, sharing not only demographic data but personal anecdotes of their experiences. The presidents were asked 69 questions covering a wide variety of topics from the role and responsibility of the president to the motivations of those who ultimately accept the role (The full results of the survey will be published at a later date.) According to those surveyed, finding volunteers is extremely time-consuming, and out of 16 activities listed, “acquiring volunteers” was the fourth most important issue for presidents overall, following attracting new members, fundraising and resolving disputes. Synagogue presidents also identify “finding volunteers” as one of the biggest obstacles they face in actualizing their vision for their synagogues.

One would think that the synagogue, a place of such centrality and importance to our communal life, would have no issue finding individuals to donate their time. Understandably, some synagogues have dwindling/aging memberships and physically do not have enough people to step up. However, it appears that a lack of volunteers is endemic to many synagogues, even those with a flourishing membership. Upon closer examination, it becomes clear why large synagogues often struggle to find volunteers. The struggle for large synagogues is twofold: financial currency and social currency.

In large Jewish communities, congregants often have a plethora of synagogues within a comfortable walking distance, and therefore do not have to commit to one specific congregation. Rather, individuals can cherry-pick those services they enjoy the best and affiliate with multiple synagogues. For example, a person may choose to pray Friday night in a synagogue known for its beautiful singing, but on Saturday pray in a different synagogue known for its expedient services. On Sunday the same individual may go to yet another synagogue that offers a morning learning program accompanied by a free breakfast buffet. However, while this person may benefit from all these resources, he/she does not necessarily reciprocate financially and socially to every synagogue that he/she benefits from. This is different from smaller Jewish communities whose congregants are fully committed to the sole Orthodox synagogue in the vicinity.

Another factor is not only the quantity of synagogues within a given area but the number of congregants in a given synagogue. Often, congregants in large congregations are under the false impression that if they do not step up, then another person will. As a result, there is often a small core group that takes on all responsibility and may become disgruntled by the lack of contribution of others in their community. This small group is often composed of those who first helped to establish the synagogue, before it grew to its present size. Additionally, congregants might believe that paying membership fees absolves them from contributing their time, an arguably equally important resource.

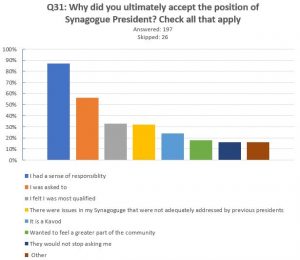

Why is it that individuals like the president chose to donate so much of their time while others in the community are hesitant to step up? The truth is that if you ask, most presidents would say that they did not want to be the president. Most presidential candidates have to be asked more than once to become president and according to the survey 4% of respondents had to be asked more than four times before agreeing to accept the position. So why do presidents ultimately accept the position? The classic response is that it must be the kavod and there is certainly some merit to that. 24% of survey respondents indicated kavod as a motivating factor in accepting the position of synagogue president. And research has shown that the pursuit of esteem and prestige is a psychological need on some level. However, out of nine different possible categories, kavod was only ranked as number five. The most important motivation was the sense of responsibility that presidents have to their community, a responsibility often ingrained in them from a young age. 55% of synagogue presidents surveyed have a family history of lay leadership and grew up in environments that encouraged and modeled volunteerism. One president surveyed had been involved in volunteer work since she was 15 years old. Another president commented how his family’s history of service to his synagogue, both in its establishment and administration, influenced his decision to become a lay leader in his community. “I followed my role models.” Similarly, another president commented how both his father and uncle served as president, influencing his decision to serve two terms as president in his own synagogue.

Why is it that individuals like the president chose to donate so much of their time while others in the community are hesitant to step up? The truth is that if you ask, most presidents would say that they did not want to be the president. Most presidential candidates have to be asked more than once to become president and according to the survey 4% of respondents had to be asked more than four times before agreeing to accept the position. So why do presidents ultimately accept the position? The classic response is that it must be the kavod and there is certainly some merit to that. 24% of survey respondents indicated kavod as a motivating factor in accepting the position of synagogue president. And research has shown that the pursuit of esteem and prestige is a psychological need on some level. However, out of nine different possible categories, kavod was only ranked as number five. The most important motivation was the sense of responsibility that presidents have to their community, a responsibility often ingrained in them from a young age. 55% of synagogue presidents surveyed have a family history of lay leadership and grew up in environments that encouraged and modeled volunteerism. One president surveyed had been involved in volunteer work since she was 15 years old. Another president commented how his family’s history of service to his synagogue, both in its establishment and administration, influenced his decision to become a lay leader in his community. “I followed my role models.” Similarly, another president commented how both his father and uncle served as president, influencing his decision to serve two terms as president in his own synagogue.

Regardless of family history, 94% of respondents said that they have had previous experience in volunteerism both in and out of the synagogue. Presidents are involved in their local schools, offer their time in nursing homes and participate in organizations like bikur cholim. And over 90% of presidents surveyed served on their synagogue’s board before becoming president. Ultimately, the decision to accept the position is very personal. Here is a small selection of the responses received:

- I had a great desire to serve.

- I (mistakenly) thought it would be beneficial socially.

- They voted me in despite my protests.

- No one else would step up.

- I had a vision for the community & our organization that I felt capable and competent to enact and lead others to actualize.

- The former president made Aliyah and per our constitution I succeeded

How can we encourage more congregants to volunteer their time? The first thing to remember is that advocacy does not start from the bima but from the synagogue youth groups and the home. As seen by many of the presidents surveyed, children who are raised in an environment where volunteerism is encouraged and modeled are more likely to participate in their synagogues as adults. The next step is transparency. Congregants have little to no idea of the efforts needed to maintain their synagogue from day to day. Congregants should have some awareness of the fiscal cost of running a synagogue as well as how their funds are being used. By involving them in the process, congregants will be more inclined to donate money to the causes that matter the most to them, whether they be social or religious programming. Synagogues also need to better communicate their manpower requirements, as many congregants are unaware of the effort needed to get a job done, whether that be planning the synagogue dinner or putting up the community succah. Congregants may be very good at offering suggestions for synagogue improvement, but they “don’t want to participate in the work necessary to get the job done.” Perhaps synagogue members should be required to commit a minimum number of hours to the synagogue. A “social budget” can be made available to congregants at the beginning of each quarter, listing all of the projects planned and the manpower necessary to fulfill them. This will allow members to participate in those projects that mean the most to them. There may be some who find this idea antithetical to the organic volunteer spirit of synagogues of the past. However, the reality of today is that the maintenance of most modern synagogues follows a business model with formalized positions. More and more synagogues are putting clauses in their constitutions for formal succession roles for the president. And if congregants refuse to step up on their own, whether from ignorance or a lack of desire, then volunteerism in general must become more formalized as well.

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.