With its haunting melody, Kol Nidrei is the piyut most closely associated with the start of Yom Kippur – setting the tone for the solemnity and awe of the day. We chatted with OU Director of Torah and Halacha Initiatives, Rabbi Ezra Sarna, about its origins and significance. The following has been edited for brevity.

When was Kol Nidrei composed, by whom, and at what point was it incorporated into the Yom Kippur liturgy?

Rabbi Sarna: We do not know who composed Kol Nidrei. The prayer dates back to the period of the Gaonim, though at first it was not widely accepted. In fact, the two great centers of Torah learning in Bavel — the yeshivos — did not recite Kol Nidrei before Yom Kippur. Their roshei yeshiva even questioned its validity and argued against adopting it as a practice. Over time, however, more and more communities began to include it, until it ultimately became a universally accepted custom with few exceptions.

Why is Kol Nidrei recited in Aramaic? While Aramaic may once have been a common spoken language, most of our tefillot are in Hebrew. Isn’t it striking that this central tefillah — the very one that “launches” Yom Kippur — is not in lashon hakodesh? Doesn’t that raise the question of whether accessibility and understanding were prioritized here?

Rabbi Sarna: The fact that Kol Nidrei launches Yom Kippur is purely a technicality. It’s actually not a tefillah at all; rather, it’s either a legal statement for the future or an annulment of past nedarim and shevuos, depending on the custom. Since one cannot do Hataras Nedarim on Shabbos or Yom Tov, we recite Kol Nidrei before Yom Kippur starts.

As for Kol Nidrei being in Aramaic, we recite many tefillos in Aramaic, such as “Breech Shemei” before Torah reading, Kaddish, the Shabbos zemer Kah Ribon, “Kol Chamira” after Bedikas Chamtez, and “Ha Lachma Anya” at the Seder. The reason they are in Aramaic is because that was the language of the nation and the chachamim wanted people to understand what they were reciting.

Although we do not speak Aramaic today, we have maintained Kol Nidrei in Aramaic in keeping with tradition. The good news is that Aramaic is close to Hebrew, and many of the words are similar; sharing the same roots for words and just slight differences in the prefixes and suffixes. If a person invests a bit of time in understanding the Aramaic, or just refers to the English translation, they should be fine.

What is the connection between the introduction and the text that follows? Just before Kol Nidrei we declare, “Anu matirin l’hitpalel im ha’avaryanim — we permit ourselves to pray with transgressors.” Immediately afterward, we begin annulling vows. That sequence seems to imply that breaking a shvua is considered the most serious transgression, even more so than other sins — including those listed in the Aseret Hadibrot — which on the surface appear far weightier.

Rabbi Sarna: To my knowledge, there is no connection between Kol Nidrei and “Anu matirin.” Chazal teach that at any taanis tzibbur where the Jewish people are doing teshuva and asking Hashem for forgiveness, the reshaim and avaryanim who have done teshuva must be included. Their presence is essential for Hashem to accept our tefillos.

The chachamim give a mashal: the ketores in the Beis Hamikdash consisted of many spices, and its fragrance was beautiful. But among the spices was the chelbona, which on its own gave off a foul odor. In the same way, when we want our tefillah as a unified tzibbur to be accepted, we need the reshaim who have done teshuva to be included. Their past may smell like chelbona, but someone who can face Hashem, others, and the shame of his aveiros while striving to do better creates a powerful Kiddush Hashem. And it doesn’t matter when they did teshuva — even if it was five minutes before Yom Kippur. These avaryanim and reshaim may have done serious things, causing them to be excommunicated from the community. Right before Yom Kippur, we make a public declaration that we are now officially allowing them, those that have had a change of heart and are seeking teshuva, to come and to daven with us, so that they can be part of our ketores offering. They can be the chelbona that adds extra beauty, extra fragrance to our communal tefillah.

Why is Kol Nidrei phrased in the future tense? If it preemptively exempts us from vows in the coming year, doesn’t that risk diminishing the gravity of making promises in the first place? Wouldn’t such a formulation discourage caution rather than promote it?

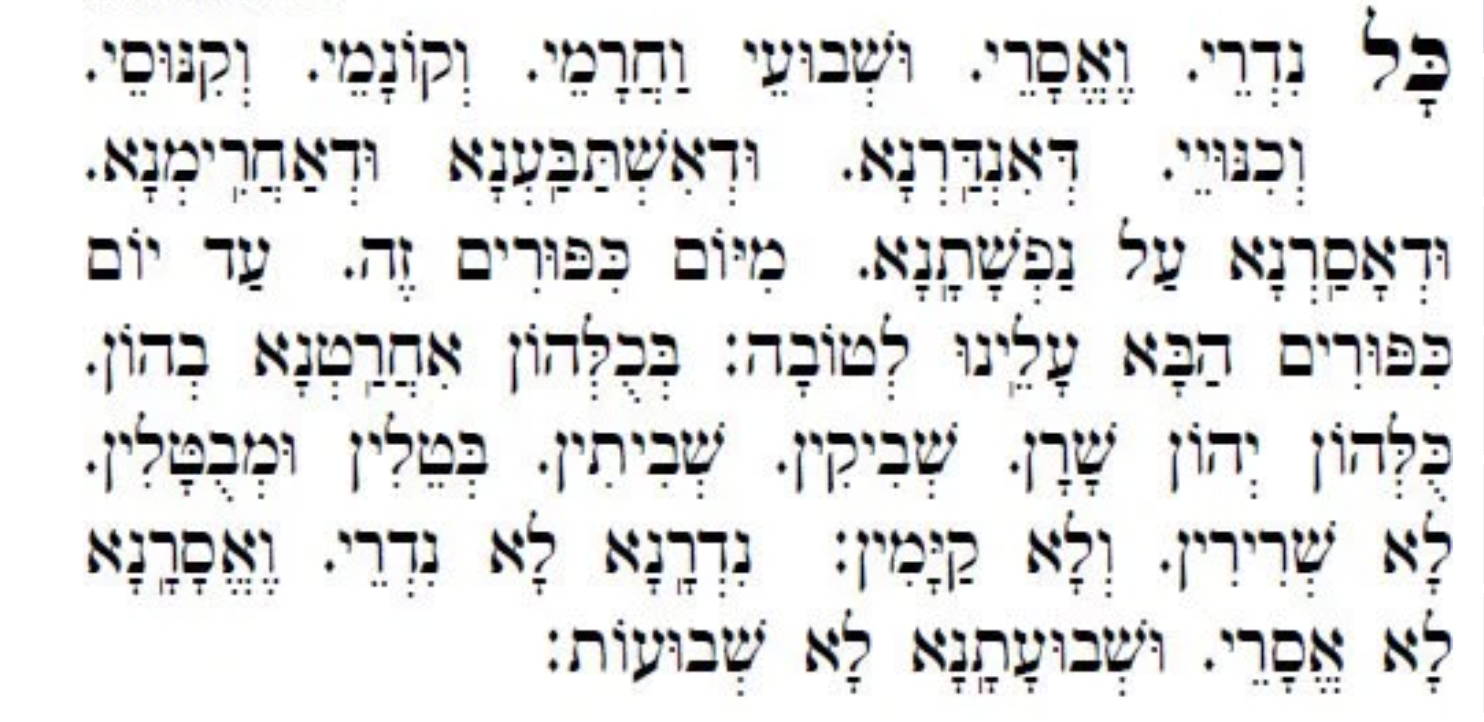

This is a large halachic discussion. In short, the older texts of Kol Nidrei, and the ones that sephardic communities still say today, were all phrased in the past, and they would say, “Me’Yom Kippurim sheavar, ad Yom Kippurim Zeh — From last Yom Kippur, until this Yom Kippur.” The point of the text was to annul vows made in the past year. Many Gaonim and Rishonim felt that it was ineffective because one can’t just proclaim, “Any vow I made over the past year is now undone.” There are detailed halachos for how to annul nedarim, and they held that Kol Nidrei, phrased that way, simply wasn’t valid halachically.

Rabbeinu Tam came along and said: if anything, Kol Nidrei could only work for the future, not the past. So he changed the nusach to say, “From this Yom Kippur until the next one.” In other words, what we’re declaring is that any nedarim we might take on in the coming year shouldn’t take effect. Ashkenazim follow Rabbeinu Tam’s version. Still, the actual effectiveness of Kol Nidrei is very limited — and from a halachic standpoint, Kol Nidrei only helps cancel future vows if at the time of taking those future vows, the person didn’t remember saying Kol Nidrei.

The fact that Kol Nidrei is recited with such a stirring melody, I imagine, came from the chazzanim rather than the rabbanim. But to me, the more powerful focus is on “Anu matirin” and the Kiddush Hashem that each person can create. It’s about thinking of Klal Yisrael as a whole — the sacrifices others have made to come closer to Hakadosh Baruch Hu, the sacrifices we ourselves can make, and the responsibility we all share to help bring other Jews closer as well. I think those are some very humbling and appropriate thoughts with which to welcome Yom Kippur.

As Director of the OU’s Torah and Halacha Initiatives, Rabbi Sarna works to solve halachic challenges that face North American Jewry and support smaller organizations in their work to enhance halacha observance. He is currently involved in creating new systems, technology and partnerships that will affect various areas of halacha and his door is always open for new ideas that could benefit Mitzvah observance. Prior to joining the OU, he served for four years as communal Rabbi in Dallas and subsequently for three years as Head of School of a High School in Houston. Originally from Montreal, Rabbi Sarna is a musmach of Yeshivas Ner Yisrael of Baltimore.