The Coming Week’s Daf Yomi by Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz

This essay is based upon the insights and chidushim (original ideas) of Talmudic scholar Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, as published in the Hebrew version of the Steinsaltz Edition of the Talmud.

Menahot 107a-b: Pledging to bring a sacrifice – I

How do we interpret the intention of someone who commits to bringing a sacrifice, but isn’t clear about his plans?

The Mishnah on today’s daf offers answers to that question, as well as to the question of how to deal with someone who says that he made a commitment to bring a specific sacrifice, but now does not remember what he said at that time. In this second case, the Mishnah tries to work out how to be sure that all possibilities are covered; in the first case, the Mishnah tries to work out how we understand what the person most likely meant.

Thus, if a person said, “I accept upon myself to bring a burnt-offering,” the Tanna Kamma rules that he should bring a lamb, which is the least expensive burnt-offering that can be brought from an animal; Rabbi Elazar ben Azariah rules that he can bring a sacrifice from fowl, as well. The Gemara explains that there is really no argument between these tannaim – in the Tanna Kamma’s community, standard use of the term “burnt-offering” referred only to an animal sacrifice, while where Rabbi Elazar ben Azariah lived, the term was used for sacrifices from birds, as well.

While Rashi understands that the ruling of the Tanna Kamma is based on the principle that a standard statement is always understood to mean the smallest of that category, the Rambam disagrees. According to the Rambam, a standard statement should always be interpreted to mean the largest of that category. Some explain that the case in our Mishnah must be understood as referring to a place where everyone referred to a lamb when using the terminology of a simple burnt-offering. Others point to a Tosefta that appears to argue with the ruling in the Mishnah; they suggest that the Rambam must have chosen to rule like the Tosefta rather than the Mishnah. Finally, some suggest that although the basic law is like the Mishnah, the Tosefta is referring to someone who wants to fulfill a higher level obligation.

Menahot 108a-b: Pledging to bring a sacrifice – II

On yesterday’s daf we learned about the challenges involved in interpreting the intention of someone who commits to bringing a sacrifice, but isn’t clear about his plans. The Mishnah on today’s daf discusses a similar case, one where the person says that he wants to bring one of his lambs or one of his oxen as sacrifices. In this case, where he is clear that he wants to bring a lamb or an ox, the Mishnah rules that if he owns two lambs or two oxen, it is the larger and more expensive one that should be brought.

Based on this ruling the Gemara concludes that we assume that someone who chooses to sanctify something does it in a generous, munificent manner – makdish, be-ayin yafah makdish.

This conclusion leads achronim to ask how this works with the simple understanding of the conclusion of yesterday’s Gemara, according to which a standard statement is always understood to mean the smallest of that category, so that someone who says, “I accept upon myself to bring a burnt-offering,” should bring a lamb, which is the least expensive burnt-offering that can be brought from an animal. If the principle is makdish, be-ayin yafah makdish, however, why shouldn’t we assume that a standard statement refers to the most expensive animal?

In his Netivot ha-Kodesh, Rabbi Avraham Moshe Salmon of Kharkov explains that

we only apply the rule of makdish, be-ayin yafah makdish when we are determining the quality of the pledge within a known category of animal, as is the case in the Mishnah on today’s daf. In a case, however, where we need to determine the person’s more general statement – as in the Mishnah on yesterday’s daf, where the man simply said “I accept upon myself to bring a burnt-offering” – we cannot assume that his intention was the largest type of animal, so because of the doubtful situation we rule that he need only bring the smallest type of animal.

According to the Rambam on yesterday’s daf, the rule makdish, be-ayin yafah makdish applies in that case, as well.

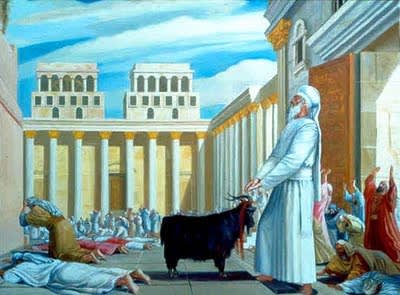

Menachot 109a-b: The Jewish Temple in Leontopolis

Aside from the first and second Temples in Jerusalem, the only other Jewish Temples where sacrifices were brought were built by Jewish priests in Egypt. The Mishnah on today’s daf teaches that someone who pledged to bring a sacrifice must bring it in the Temple in Jerusalem, and not in Bet Honyo – the Temple of Onias. Even if the person specifically committed to bringing the sacrifice there he cannot do so, rather he must bring it in Jerusalem.

The Gemara quotes a baraita that brings two opinions about the Temple of Onias. According to Rabbi Me’ir, that temple was a place of pagan idol worship; Rabbi Yehudah rules that only Jewish sacrifices to God were brought there.

According to Josephus, the Temple of Onias was built in Leontopolis in Egypt by the son of the High Priest Onias III, sometime around the year 155 BCE. This temple was modeled after the Temple in Jerusalem. According to the Talmud (Menahot 109b), Onias fled from Jerusalem to Egypt following a serious dispute with his brother. According to Josephus, the matter was connected with the Hellenists in Jerusalem, and, after a time, with the Hasmonean dynasty that claimed the High Priesthood in Jerusalem.

As we have learned, there is a disagreement about how to view the Temple of Onias, where the priests who served were all true priests – descendants of Aharon ha-kohen. It appears that the accepted position is that this was not a house of pagan worship; the most serious problem with it was the fact that a temple where sacrifices were brought that existed at the same time as an operating Temple in Jerusalem is forbidden, and participating in the sacrificial service there was punishable by karet (a serious heavenly punishment). Nonetheless, the Mishnah rules that kohanim who served there were not welcome to serve in the Temple in Jerusalem.

According to Josephus, Vespasian closed the Temple of Onias about three years after the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem, but it is possible that the service there was revived at a later time.

Menachot 110a: What takes precedence – learning Torah or marriage?

In the closing daf of Masechet Menahot, the Gemara discusses the state of Diaspora Jewry and quotes a passage from Sefer Malakhi (1:11) where the prophet discusses how God’s Name is known throughout the world, where “pure offerings” are presented to Him in all places.

The “pure offering” mentioned is interpreted by the Gemara as referring metaphorically to a man who first marries and then studies Torah.

Tosafot point out that this teaching is, in fact, the subject of some discussion in Masechet Kiddushin 29b. There we find an apparent disagreement on this matter. Rav Yehudah quotes Shmuel as ruling that a person should first get married, and can study Torah later; Rabbi Yohanan objects, arguing rehayim be-tzavaro ve-ya’asok ba-Torah!? “with a millstone – i.e. the responsibilities of supporting a family – on his neck, how can he study Torah!” He concludes that a person should study Torah first and get married afterwards.

The Gemara concludes that there is really no disagreement between Rav Yehudah and Rabbi Yohanan – ha lan ve-ha lehu – we must recognize the differences between the communities in Bavel and Israel. What the Gemara does not explain is which ruling is appropriate for which community and why that would be the case.

Rashi explains Shmuel’s ruling as applying to students from Bavel who traveled to Israel to study. Since they were not at home, they were not responsible for supporting their families, and could marry first. Rabbi Yohanan was talking to Israeli students who remained at home and could not divest themselves of their responsibilities. They were, therefore, encouraged to study first and marry later.

Tosafot do not accept Rashi’s explanation. They are disturbed by the idea that a man can choose to abandon his family in order to travel to a foreign land and study. Furthermore, the ruling that encouraged marriage before study was made at least partially to allow a man to learn Torah while having satisfied his natural sexual urges; if he leaves his wife behind in Bavel, this is not accomplished. Rabbenu Tam suggests that Rabbi Yochanan was telling the poor students of Bavel that they should come to Israel for study before they take on the responsibilities of a family, while Shmuel was telling the wealthy Israeli students that they could marry, since they would remain at home during their studies.

Some rishonim follow Rashi’s approach, but with a different explanation. In Bavel tradition allowed young women to work and support the family, so students who made such an arrangement could first marry. In Israel, where the entire responsibility of support was on the husband, students were told to first learn Torah and to marry later.

In addition to his monumental translation and commentary on the Talmud, Rabbi Steinsaltz has authored dozens of books and hundreds of articles on a variety of topics, both Jewish and secular. For more information about Rabbi Steinsaltz’s groundbreaking work in Jewish education, visit www.steinsaltz.org or contact the Aleph Society at 212-840-1166.

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.