The Coming Week’s Daf Yomi by Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz

This essay is based upon the insights and chidushim (original ideas) of Talmudic scholar Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, as published in the Hebrew version of the Steinsaltz Edition of the Talmud.

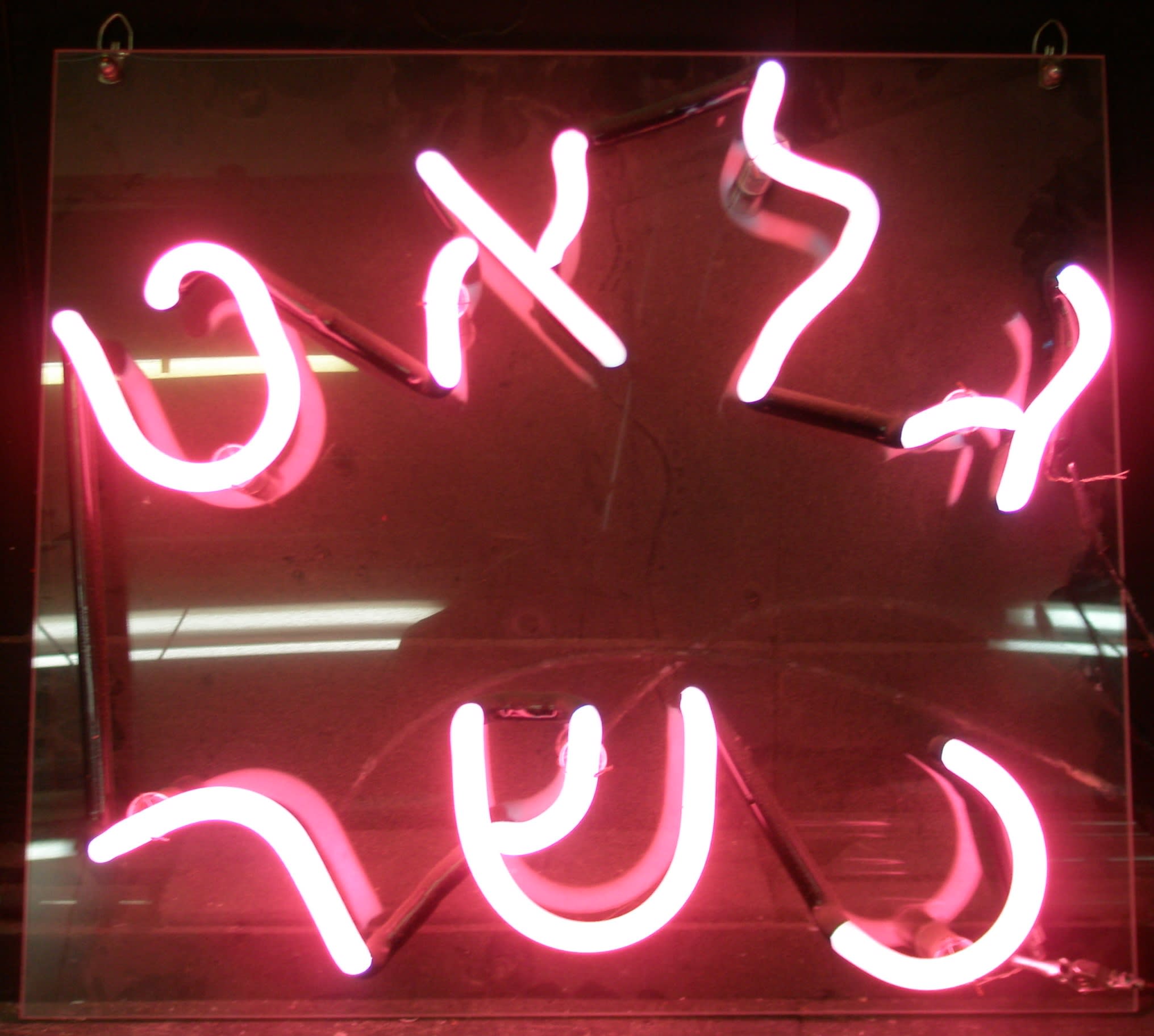

Chullin 40a-b: Slaughtering someone else’s animal for idol worship

The Mishnah teaches that if someone slaughters an animal for idol worship – e.g. for mountains, hills, seas, rivers or deserts – the shechita is invalid. What if the animal that is slaughtered belonged to someone else? Is it possible to forbid someone else’s property?

Rav Huna teaches that if someone’s neighbor’s beast was lying in front of an idol, then as soon as he has cut one of the organs of the throat – either the esophagus or the trachea – he has rendered it prohibited. In contrast, the Gemara brings the opinion of Rav Nachman, Rav Amram and Rav Yitzchak who rule that a person cannot render prohibited something that does not belong to him.

Rabbeinu Chananel suggests that even according to this last opinion, if the person performed a full act of shechita, the animal would become forbidden. The Rabbis differ only with regard to Rav Huna’s ruling that a partial shechita is sufficient to render the animal prohibited. Rashi disagrees, arguing that Rav Nachman, Rav Amram and Rav Yitzchak believe that if the animal does not belong to him, his actions cannot prohibit it. Rashi points out that the continuation of the Gemara tries to disprove their position by bringing a case of a wine libation that is forbidden, yet a wine libation is a full act of worship. If these Rabbis agree that a full act renders the animal prohibited, then the Gemara’s question would not make sense.

Another issue discussed by the rishonim is whether Rav Nachman, Rav Amram and Rav Yitzhak who rule that someone cannot prohibit someone else’s animal would permit the animal to be eaten. Most argue that slaughter with idol worship in mind cannot be considered proper shechita, that is to say, that although his thoughts cannot render the animal prohibited, at the same time it does not render the animal kosher. The Rashba disagrees, arguing that if the animal does not become forbidden, it is permitted to be eaten.

Chullin 41a-b: Slaughtering an ordinary animal and declaring it a sacrifice

If a man slaughtered an ordinary animal outside the Temple precincts, declaring it to be a burnt-offering or a peace-offering or a guilt-offering for a doubtful sin or the Passover-offering or a thanksgiving-offering, the slaughtering is invalid; Rabbi Shimon, however, declares it valid.

According to the letter of the law, someone who makes such a statement has not accomplished anything, since this animal had not been set aside as a sacrifice, and it is unusual to consecrate it in this manner. Nevertheless, the Sages ruled that the slaughter should be considered invalid since it appears as if he is slaughtering consecrated animals outside of the Temple, and people who see this may mistakenly think that that is permitted. Rashi explains that it is for this reason that the Rabbinic enactment forbidding such slaughter only applies to those sacrifices that a person donates and not those that are obligatory. Rashi explains the continuation of the Gemara, as well, based on the approach of marit ha’ayin – the perception (or misperception) that this action will engender in others.

There are other rishonim, however, who explain that this Mishnah refers specifically to the historical period when the Temple stood, and that the concern expressed in the Mishnah relates to the fact that the man’s statements may actually confer sanctification on the animal.

The Ba’al HaTurim suggests that based on this reasoning even today when the Temple is not standing we must be concerned with the possibility that the animal becomes consecrated by means of his statement and that he is effectively performing shechita on kodashim bachutz – a consecrated animal outside of the Temple. At the same time others point out that this cannot literally be a case of kodashim bachutz since the animal is considered non-kosher, but it is not forbidden to derive benefit from it.

Chullin 42a-b: Animals that cannot live much longer

The third perek of Masechet Chullin begins on today’s daf. Following the first two chapters of the tractate whose focus was on the act of slaughtering an animal, this perek – the longest one in Masechet Hullin – deals with the animal itself, i.e., which animals are permitted and forbidden to eat. The two general categories discussed are the laws of treifah – animals that for reasons of illness or injury will die as a result of their condition – and types of animals that are not kosher and cannot be eaten.

The opening Mishnah of the perek presents a list of conditions that are considered to be terminal, and concludes with the following principle: if an animal with a similar defect could not continue to live, it is a treifah.

In defining this principle, we find a difference of opinion. The accepted interpretation is that the animal will succumb to its condition within 12 months, but others say that it will die within 30 days and one opinion in the Gemara defines it as an animal whose condition will not allow it to conceive and give birth. The commentaries discuss whether an animal would be considered a treifah if it could be treated with drugs, and whether there is reason to distinguish between different types of tereifot.

Regarding the language of the Mishnah, some ask why the Mishnah teaches “if an animal with a similar defect could not continue to live, it is a treifah,” rather than simply saying “any animal destined to die of its condition is a treifah.” One approach is to explain that the Mishnah is discussing a case where the animal has already been slaughtered and is found to have an internal injury. Is the animal kosher? The Mishnah teaches that “if an animal with a similar defect could not continue to live, it is a treifah.” The Chatam Sofer suggests that the Mishnah is teaching us that even if we find an out-of-the-ordinary case where the animal survives more than 12 months, if an animal with a similar defect could not continue to live, it is, nonetheless, a treifah.

Chullin 43a-b: Talmudic testing

As we learned on yesterday’s daf our Gemara has now turned its attention to questions of treifah – animals that have terminal conditions that will cause them to die – which would render the animal non-kosher.

On today’s daf, Rabbah teaches that if the animal suffered an injury to its esophagus that would ordinarily render it a treifah, even if a membrane grew over that spot it is considered a severe injury and the animal remains a treifah. Furthermore, in the event of an injury, the esophagus cannot be checked by looking at it from the outside; it must be checked on the inside. The Gemara explains that this is relevant specifically in a case where we are unsure whether the animal had been clawed. Inasmuch as the outside of the esophagus is reddish in color, it would difficult to ascertain whether the animal had been injured simply by examining the esophagus from the outside; it is essential to check the inside, which is white.

In this context, the Gemara relates the following story:

There once came, before Rabbah, the case of a bird about which there arose a doubt whether it was clawed or not, and he was about to examine the esophagus from the outside when Abayye said to him, ‘Did you not say: Master, that the gullet cannot be examined from the outside but only from the inside?’ Rabbah at once turned it inside out and examined it and found upon it two drops of blood, so he declared it to be a treifah.

The Gemara explains that this was not an error on Rabbah’s part, rather he was testing Abayye to see his reaction.

The practice of a teacher behaving in a manner that is not correct according to the halacha appears occasionally in the Gemara, for example regarding Hillel and his student Rabban Yochanan ben Zakkai. The point of this exercise is not only to test the students but also to teach them heightened awareness of what they observe and encourage them to review their studies in a setting of practical application.

Chullin 44a-b: Accepting multiple stringencies

On yesterday’s daf the Gemara presented a disagreement between Rav and Shmuel regarding the status of the turbatz ha-veshet, the animal’s pharynx. This area, which is where the esophagus enters the throat, is considered by Rav to be a place where ritual slaughter can take place, while Shmuel rules that it is too high up in the animal’s throat to be an appropriate place for slaughter. When a practical situation of shechita in this area was brought before Rava, he applied both Rav’s position and Shmuel’s position to rule stringently in that case.

Rava’s ruling leads Ravina‘s son Mar to quote the following baraita:

The halakhah is always in accordance with the ruling of Bet Hillel. Nevertheless one who desires to adopt the view of Bet Shammai may do so, and one who desires to adopt the view of Bet Hillel may do so. One who adopts the view of Bet Shammai only when they incline to leniency, and likewise the view of Bet Hillel only when they incline to leniency, is a wicked person. One who adopts the view of Bet Shammai only when they incline to strictness and likewise the view of Bet Hillel only when they incline to strictness, is a fool and to such an one applies the passage in Kohelet (2:14): ‘But the fool walketh in darkness.’ But one must either adopt the view of Bet Shammai in all cases, whether they incline to leniency or strictness, or the view of Bet Hillel in all cases, whether they incline to leniency or strictness.

In fact, this baraita should not be understood to mean that a person may never choose to be stringent by following two different opinions, since we find general principles of halakhic rulings – e.g. ‘regarding biblical questions follow the stringent view; regarding rabbinic questions follow the lenient opinion,’ see Avodah Zarah 7a – that may lead to such conclusions. It is only in situations where the stringency stems from the application of two rulings that stand diametrically opposed to one another that the person who adopts both is considered to be behaving foolishly. Rava’s ruling clearly fell into that category.

Chullin 45a-b: Finding the appropriate spot for ritual slaughter

Rabbi Chiya bar Yosef taught the following in the presence of Rabbi Yochanan: The whole of the neck is the appropriate place for slaughtering – that is, from the large ring to the bottommost lobe of the lung. Rava said: ‘The bottommost lobe’ really means the uppermost lobe, for I hold that the appropriate place for slaughtering is the entire extent of the neck observed at the time when the animal is grazing. But on no account may the organs of the throat be stretched by force.

The lungs look like two wings that are divided into lobes on either side of the windpipe that is stretched between them until it reaches the bottom of the lungs. According to Rava, the appropriate place for ritual slaughter on the windpipe extends until the area opposite the lobe that is closest to the animal’s head, which is at the bottom when the animal is hanging by its feet, but at the top when the lungs are held up by the windpipe. This explanation stands in contrast with the simple reading of the baraita which could be understood to mean that the place of ritual slaughter extends to the very bottom of the lungs, the place where the windpipe enters them.

The Ba”h explains that the baraita used the expression “bottommost” in order to indicate that the animal should be checked after slaughter by hanging it upside down, since in that positions the lobes spread out and can be examined more easily.

A common misperception is that a giraffe cannot be slaughtered because we do not know where on its neck shechita can be performed. In fact, as we learn on today’s daf, ritual slaughter can be performed anywhere on the animal’s neck, which means that while a pigeon may only have a few inches for shechita and a cow about a foot, a giraffe would have six feet of room for slaughter to be performed. (See “What’s the truth about…giraffe meat?” for more details.)

Chullin 46a-b: What is “Glatt Kosher”?

What is “Glatt Kosher”?

On today’s daf we learn that Rava taught: If two lobes of the lungs adhere to each other by fibrous tissue, they cannot be checked to render the animal permitted. This is so, however, only if the lobes were not adjacent to one another, but if they were adjacent it is permitted, for this is their natural position.

A normal set of animal lungs contains a number of lobes – three on the left side and two on the right side – aside from the two larger lobes at the bottom. It is a common occurrence for viscous mucus to leak from one lobe and thicken on another one of the lobes.

There are two main approaches in the rishonim in explanation of these adhesions. According to Rashi, they are indicative of a hole in the lung of the animal that has been covered by hardened mucus, and the animal cannot be permitted because a hole in the lung indicates that the animal is a treifah – it is terminally ill, and therefore not kosher. Tosafot argues that this is a normal occurrence and does not indicate that the animal had a hole in its lung. Nevertheless, when the adhesion breaks off it will cause a hole to be formed in the lung, and the animal is therefore viewed as already considered a treifah. The Gemara‘s ruling is that the animal’s lungs cannot be checked, that is, even if they are filled up with air to see whether there are holes, since we already know that there is either already a hole or there is bound to be one in the future, checking for a hole is moot.

According to the view of modern medicine, adhesions on the lungs stem from infections. The most common situation is when the animal suffers from infections in the chest membrane. When that occurs, the body secretes substances to build up the internal tissues. Appropriate care and avoidance of cold can significantly lower the incidence of such adhesions in animals.

The Shulchan Aruch (Yoreh De’ah 39:4, 10, 13) rules that we do not distinguish between thick and thin adhesions – all are considered to be problematic and the animal is rendered a treifah that cannot be checked. The term “Glatt” refers to this ruling, since the animals lungs are required to be totally smooth. The Rama disagrees and suggests that thin adhesions can be squeezed or peeled off, after which the lungs can be checked for holes.

In addition to his monumental translation and commentary on the Talmud, Rabbi Steinsaltz has authored dozens of books and hundreds of articles on a variety of topics, both Jewish and secular. For more information about Rabbi Steinsaltz’s groundbreaking work in Jewish education, visit www.steinsaltz.org or contact the Aleph Society at 212-840-1166.

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.