This article originally appeared at thejc.com.

The latest stir in America’s modern Orthodox community has come from an article by Jay Lefkowitz in Commentary, called “The Rise of Social Orthodoxy.” Lefkowitz considers himself to be social Orthodox, which means that he largely observes halachah, but not because he (necessarily) believes that God commanded him.

The latest stir in America’s modern Orthodox community has come from an article by Jay Lefkowitz in Commentary, called “The Rise of Social Orthodoxy.” Lefkowitz considers himself to be social Orthodox, which means that he largely observes halachah, but not because he (necessarily) believes that God commanded him.

For Lefkowitz, Jewish observance has a different motivation. It connects him to a community with all the benefits of support and belonging which that brings. God, whether or not He exists, is very much secondary. In his search for a life of meaning, Lefkowitz has found that being part of a people, with a history and identity, answers a need.

It is difficult for a rabbi to respond. On the one hand, mitzvot are mitzvot. If the social Orthodox are lighting candles, putting on tefillin, drinking four cups of wine on Seder night and learning Torah, that is wonderful. It would be tragic if by insisting on faith in addition to practice, we reduced the performance of mitzvot. It would be distressing to hear someone say: “If you say my practice is meaningless without belief, then fine, have it your way. I won’t keep Shabbat anymore.”

So the first responsible response to social Orthodoxy is to be thankful that Jews are observing halachah, whatever their reasons. After all, the Talmud tells us mitoch lo lishma, ba lishma, even if the initial motives are not ideal, they will become so (Sanhedrin 105b). The sages were patient and had faith that even if the right intentions were not always there, eventually they would emerge. I am sure that in many cases it is true. Faith often varies over the course of a lifetime, but when we tell people they are not good enough, we can put them off entirely.

But there are still concerns, both in practice and in principle. It is hard to transmit the sense of commitment without commandedness. How can parents make a compelling case for their children to continue to fast on Yom Kippur or light Chanukah candles on the basis that it gives them a sense of community?

The children can respond “I don’t want it” or “I don’t need it”. They can claim that they express their Judaism through holidays in Israel or that their identity is primarily as a member of their family and they reinforce that by getting all the cousins together to have a big lunch on December 25. Mordecai Kaplan was one of the most brilliant Jewish thinkers of the 20th century, and he founded an entire movement with an alternative to a traditional God as the basis of observance. For Kaplan, mitzvot were meaningful as “Jewish folkways”, the religious way in which Jews have chosen to express themselves. His denomination, Reconstructionism, is only 100 synagogues strong and was recently in severe financial trouble. Kaplanism is interesting, but it seems not to work on the ground.

These practicalities aside, there must be major religious objections to social Orthodoxy. We are about to celebrate Shavuot. Although it has a strong agricultural component, for most of us it is primarily the celebration of the giving of the Torah. Whereas Pesach and Succot are very busy festivals — eating matzah, shaking the lulav and etrog — Shavuot is at heart quiet and reflective. The customs of staying up to learn on the first night and eating milky foods were relatively late developments.

Shavuot is not a festival for doing, it is a festival for thinking about why we do what we do. The answer of Shavuot is not the answer of social Orthodoxy. It exceeds the communal. Pesach and Succot are built around social elements. The Paschal lamb was eaten in a large group, the mitzvah of Succah applies to kol ha’ezrach b’Yisrael, members of the nation, and not to others. They are bonding rituals.

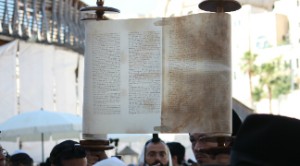

Shavuot is different. The classic mitzvah of Shavuot was the bringing of bikkurim (first fruits) to the Temple, when the farmer would declare “now I bring the first fruits of the soil that you, Lord, have given me”.

The focus of Shavuot is not social, about being part of a people, important though that is. Shavuot is about God and His commandments. On Pesach we became a nation, but Shavuot is the fulfillment of Pesach, because it was the moment when we became a nation called by God to His service and we answered that call.

Shavuot takes us beyond social Orthodoxy. Observance, done for whatever reason, should not be devalued, but Shavuot gives us an additional challenge. Ultimately, we perform mitzvot because God revealed His will to us and when we keep mitzvot, we are not just developing a relationship with each other, but with Him. We cannot all have that in mind, or have it in mind at all times, but it is remains the ideal for which to strive.

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.