Anna’s aunt was 35 years old when she was diagnosed with breast cancer and underwent a double mastectomy. Anna’s great-grandmother had breast cancer before turning 50. Anna knew that these facts were spotlights shining on her own genetic makeup, but until she switched doctors last winter, she hadn’t been approached to be tested. She had heard about the option but, at age 30, she had never been counseled to undergo any kind of genetic testing for hereditary links to cancer.

“My doctor was honest and upfront with me. She said, ‘you know that when you get the results, it could mean life as you know it will change,’” Anna recalled. “And sure enough, I’ll never forget, at 8:30 in the morning on a Tuesday, the doctor called when I was at work, and I went into a conference room when she broke the news [that I tested positive for the BRCA2 gene mutation.] I was shocked. Of course I cried. And then it hit me, ‘well, now what am going I do?’”

The BRCA genes (BRCA1 and BRCA2), found within the DNA of each person, protect the body against cancer. Yet one in 40 Ashkenazi Jews carries a mutation in a BRCA gene, which are passed down in families, according to The Program for Jewish Genetic Health, an initiative of Yeshiva University and its Albert Einstein College of Medicine. When these genes have changes, or mutations, they cause an increased risk for breast and ovarian cancers.

In general, individuals who may be carriers of a hereditary cancer mutation and may be at risk for breast and ovarian cancer include those with a family history of diagnosis at an early age (younger than 50 years old); with two or more close relatives on the same side of the family who have been diagnosed with cancer; individuals with multiple primary cancer diagnoses (as opposed to metastatic cancer); bilateral or multiple rare cancers; the same or related cancer types running in the family (for example, breast or ovarian); or evidence of cancer susceptibility being passed down from parent to child.

“Ashkenazi Jewish ethnicity confers its own risk for BRCA mutations,” emphasized Dr. Susan Gross, professor of clinical obstetrics and gynecology; and women’s health, pediatrics and genetics at Albert Einstein College of Medicine; founding director of the Program for Jewish Genetic Health; and chief medical officer of Natera, a California-based medical diagnostics company.

“The risks are so substantial if you are of Ashkenazi Jewish background that family history and age can even become less of a factor. It is confusing for precisely this reason.”

Geneticists say that one in ten Ashkenazi Jewish women with breast cancer and one in three Ashkenazi Jewish women with ovarian cancer are likely to have a BRCA mutation, according to the Program for Jewish Genetic Health. Males can also carry BRCA mutations.

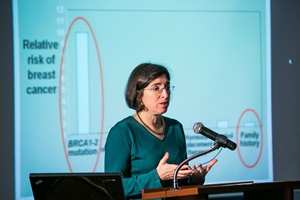

The Orthodox Union recently presented an educational interactive webinar for rebbetzins, yoatzot halacha (women certified by Orthodox rabbis to be a resource for women with questions regarding areas of Jewish Law that relating to marriage, intimacy and women’s health) and kallah (bride) teachers on “Breast and Ovarian Cancer in our Community: Genetics, Knowledge and Prevention” led by Dr. Gross. The event was held in partnership with the Yeshiva University Program for Jewish Genetic Health and the Albert Einstein College of Medicine of Yeshiva University; and co-sponsored by the Rabbinical Council of America (RCA), Yeshiva University Center for the Jewish Future, and the National Council of Young Israel.

The full webinar may be watched at www.ou.org/BRCA.

“The Jewish community has championed educational awareness and testing for the prevention of diseases linked to those of Jewish heritage (compared to the general population), such as Tay-Sachs and Cystic Fibrosis, but knowledge and testing for BRCA mutations are not as well-known as they should be,” said Rebbetzin Judi Steinig, associate director of OU Community Engagement, and webinar coordinator. “Testing is about prevention. Testing is about saving lives.”

Dr. Gross emphasized that BRCA mutations cause a significantly increased risk for breast and ovarian cancer (among others), yet women who have BRCA mutations have options to reduce their cancer risks.

Anna, a rebbetzin who lives in Manhattan with her husband, attended the live taping of the webinar at OU headquarters in Manhattan, at which she shared her story to the audience of women and Dr. Gross during a question and answer session following the main presentation.

Anna shared, “[When I found out] I was shocked, and really didn’t know what to do. Fortunately my doctor is part of the Mount Sinai network, and is very proactive. She told me ‘you have to do this, then this, then this, then this’ and I just said, “Whoa, you have to slow down. This is a lot of information right now. Where do I begin?’ First, I met with a genetic counselor and we mapped out options and risks. From there, now I have a team comprised of my genetic counselor, a gynecological oncologist at Mount Sinai, and a personal physician who is part of the Dubin Breast Center of Mount Sinai.”

Anna noted that every family reacts differently. Originally her mother never wanted to be tested and was “taken aback” when her daughter chose to do so, Anna pointed out. “I am happy that I know,” Anna emphasized. “I’m able to make some personal decisions with my husband about how we want to make out—as my doctor calls it—“the ten year plan” about the types of treatment we want to pursue. It’s also controversial, because options such as prophylactic surgeries come with a lot of stigma. …I don’t think anyone should feel pressured into one treatment or another. A treatment plan is a very personal decision between you and your team of physicians.”

In recent months, Anna’s mother has changed her mind and plans to be tested, knowing she has a 50/50 chance of carrying a BRCA mutation. “The big thing I would stress is that getting tested is very, very personal decision,” Anna stated. “Yet I feel it’s a very important decision—especially if you have a history. I respect that some people aren’t sure what to do with the information. I feel getting information will help them to demystify so that people aren’t scared to get tested. When you get the diagnosis, it’s a lot to handle. Knowledge is power. Knowledge is life.”

With tears welling in her eyes, Dr. Gross thanked Anna for sharing her story, predicting that Anna’s bravery would inspire others to be tested, and could lead to, for instance, another Jewish mother living to be at her son’s bar mitzvah celebration next summer.

“The more we begin speaking about this and educating our community, the more lives we can save,” Dr. Gross stressed.

For more information on Jewish genetic health, visit www.yu.edu/genetichealth or MyJewishGeneticHealth.com, contact JewishGeneticHealth@yu.edu, or call 718.430.4156.

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.