The stage is set – the table is bedecked in fine linen; the chairs, with soft pillows. The props are in place – the Seder plate, Elijah’s cup, the matzot. The players are in their places, reclining with their scripts, their haggadot, at hand. The lights (candles) go up. There is a hush as the youngest enters the room and gazes upon the scene before him. “How different is this night from all others!”

Different indeed.

And no accident that the youngest child is called upon to utter the enthralling words that have enlivened the Seder ritual for hundreds upon hundreds of years. The central commandment of our Passover Seder obligation is to tell and to teach. On that day, you shall tell your son what the Lord, your God, did for you in bringing you out of Egypt…

Among many other things, our ancient rabbis were brilliant educators. God had commanded that we teach our children. The question then became, How best to teach? How best to fulfill this commandment?

To engage and to reward. And to keep the focus on the student – the child. For Pesach is a holiday of children. It is right that it is so. Our Egyptian servitude and suffering was made more painful for its cruelty to our children.

“And he said, When you deliver the Hebrew women look at the birth stool; if it is a boy, kill him!” With these words, Pharaoh sought to cut off our future by denying us a generation of children. He demanded that, “…every son that is born… be cast into the river…”

Why did the Pharaoh cause such suffering against the Jewish people? For no other reason than we multiplied. We became numerous. We gave birth to children, in accordance with God’s command to “be fruitful and multiply.” However, Pharaoh felt threatened by our numbers. “The children of Israel proliferated, swarmed, multiplied, and grew more and more.”

How great was Pharaoh’s hatred of the Jews and our children? How threatened did he feel? So much so that the Midrash teaches us that when the Israelites fell short in fulfilling the prescribed quota of mortar and bricks, the children were used in their stead to fill in the foundation of the store cities built in their servitude! Another Midrash describes Pharaoh bathing in the blood of young children.

When redemption was finally at hand, children were once again at the forefront of this historical and religious drama. When Moses first confronted Pharaoh with the request to be free to go into the desert to worship, he proclaimed, “We will go with our young and with our old, with our sons and with our daughters.” In making this proclamation, he was giving voice to the ultimate purpose of our redemption, found in the central command of Pesach, “You will tell your son on that day, saying: It is because of this the Lord did for me when I came out of Egypt…”

Judaism is a faith rooted in the past but which is always forward looking. Tradition loses meaning unless it is passed forward to the next generation. We do not look for individual redemption as much as communal salvation.

For that to happen, our children must thrive. They must go forward but with a solid foundation in the godly lessons of our history. The Exodus from Egypt is rife with the significant role our children played in its historical narrative.

God has commanded the teaching the story of our redemption to our children. Our rabbis have fashioned a ritual that is engaging and educational – fulfilling God’s command. So it is not surprising that a lesson about learning – the necessary compliment of teaching – is dramatized in the story of the Four Sons. Not surprising, but troubling and ironic that as we finally find our places around the Seder table we find ourselves face to face with the perplexing realization that keneged arba’ah banim dibrah Torah, that the “words of the Torah are in opposition to the four sons!

What is this? No sooner have we entered into the drama of the retelling of the lessons of the Exodus narrative than we find ourselves in conflict and discord between the Torah and each of the four sons – the wise, the wicked, the simple and the one too young to even know how to ask.

How do we make sense of a holiday and ritual devoted to children that also seems to push away those very same children? Is there real discord between the Torah and each of the four sons? Or these “conflicts”, upon deeper reflection, also point us in the direction of greater understanding? Might they not represent some deep and fundamental dynamic that exists in the generations of Jewish people themselves? Perhaps these conflicts repre¬sent perspectives and approaches to Judaism, each, while falling short of full adherence to genuine and pure Torah commitment, mirroring a chasm that grows in successive generations that our teaching is supposed to bridge.

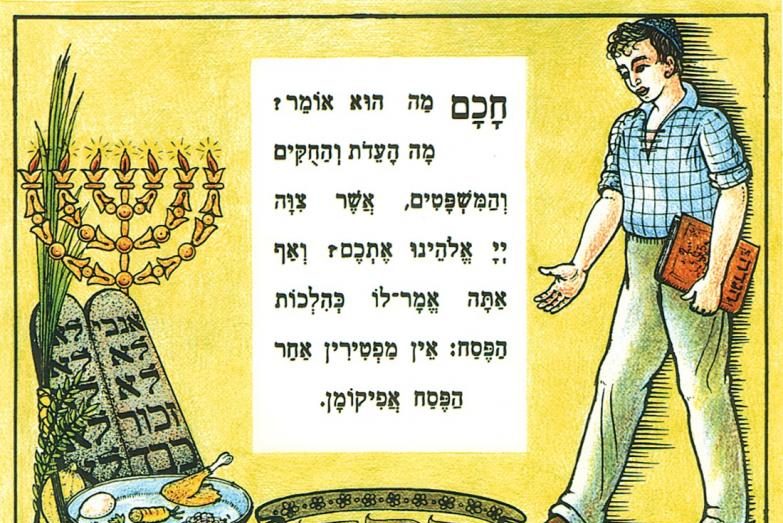

Picture first then the father. He is from the “old world.” He carries no title, no label. He personifies the saying, What you see is what you get. He does not engage in schtick. He represents no polemic. He is not a politician or manipulator. He claims no ideological purity or philosophical bent. He is, simply, a good and pious man – a man devoted to avodat Hashem, yirat shamayim. This man sires a son, a chacham. A wise son. Such a blessing! To have given birth to a wise son. The son observes the commandments. But more than that, he is an intellectual. Emunah, faith, is not sufficient for such a mind as his. He is a mindful “wrestler” with Torah. As Ben Bag Bag exhorts, he turns Torah over and over again, seeking out all its lessons. He examines the mitzvot determinedly, breaking them down into ever more exacting divisions – edot, chukim and mishpatim.

He is, without question, a believer. However, belief is not enough for him. He is not fulfilled until he understands and digests the material and lessons at his own intellectual level. “What is the meaning which our God has commanded you?” Even if the intensity and method of his inquiry is necessarily tainted – who can truly intellectually grasp these things that he seeks to understand? – we remain aware of the chacham‘s overall positive traits and go on to teach him all of Torah, from the very beginning up to and including the very last law of Pesach, the afikoman.

Moreover, we are assured that as long as the taste of matzah and flavor of Jewish observance and commitment remains with him, the chacham will continue his search for ever deeper meaning.

The chacham remains devoted to his personal religious growth. But he sets different goals and expectations for his own son, the next generation. He views the classical yeshiva education of the ‘90s as too rigid and lacking in intellectual rigor. His intellectual mind has taken in the world and its rewards as well as the teaching of Torah. He wants “more” for his own son than was available to him. He advises his son to seek a profession. “There is a bright future in computers,” he notes. He urges his son to look to the Ivy League schools, where worldly success is handed to the graduates along with their diplomas.

His son does as his father teaches. But then… he returns home at Spring break and the family Seder to arrogantly and cynically challenge his father. “What is the meaning of this service to you?!”

He has allowed the world to give him voice. He is rasha, wicked, for he no longer places himself as a recipient of Jewish tradition. In effect, he has accomplished the task that Pharaoh set up to accomplish all those generations before.

The simple son, the tam, grows up in the alienated, confusing, indifferent and “proudly” secularized Jewish home of his rasha father.

“Do we have to?” he asks when the family prepares to go to the family Passover dinner. He fumbles and stumbles through the parts assigned to him. Have they not taught him these things in the afternoon synagogue school that he attends only sporadically? his kindly grandfather wonders with concern.

The child’s sentimental memories of a caring and giving zeide are not enough to motivate him. What chance can mere sentiment have against the rapid, immoral and unethical place where he lives now? Rather than motivation to return, the tam struggles with these emotions and calls them “guilt” and guilt, he knows because the daytime talk show hosts say so, is a useless and nonproductive emotion.

The tam’s son then, finds himself so far removed from the faith and tradition that animated his father’s zeide that he doesn’t even recognize things Jewish, leaving him unable to even formulate an intelligent question. There is not, truth be told, no reason to ask. His great-grandfather is long gone, and his grandfather and father show no interest in passing along an archaic and foolish tradition. “When do we eat?” he asks, trying to circumvent the tedious haggadah. He cannot be bothered returning to the Seder table after the shulchan orech. There are television shows to watch, and computer games to play.

Indeed he is just as likely to show up to a Jewish spring party and burst out with “Happy Birthday” upon seeing the lit candles as to ask the Four Questions, as the Riskin Haggadah, instructs at the bottom of page 61.

What are we to do? Build a fence between those who love and fear Torah and the generations of the wicked, the simple and the one too ignorant to even ask? Is that what God would have us do?

God’s command is clear. It is not to “Tell your son if he is interested in hearing…” There is no qualification. The children must be told and taught. The gap must be narrowed. Fences must be brought down and bridges erected. Communication must be established and effectively maintained.

I do not minimize the task. However, as Rabbi Tarfon suggests, we are not obligated to complete the task, but we are not free to desist from it either. As daunting as the task is, the gap must be narrowed.

Fully a quarter of the sons are reshaim. So many of the sons are wicked that it is only the reshaim that the Torah speaks of in the plural! “Then, when your children say to you, what does this service mean to you?” There are so few chachamim. In the United States, there are only 150,000+ students attending Jewish day schools, and many less continue to study in intensive High Schools of Torah.

Rabbi Yechezkel Mickelsohn once asked, at least partially in jest, “Why doesn’t the Torah recommend the same solution and approach of hakeh et sheenav, blunting the teeth of the rasha, as does the Haggadah?” He answered that, while the Ba’al Haggadah speaks only of one rasha who could be successfully countered, the Torah speaks of many reshaim. To fight such a multitude is dangerous and could likely result in harm to the Jewish people.

So we are left with our “four sons” and the need to bridge the generations from father to son to son to son to communicate the miracle of our emancipation. Our first task is to bless and extol God for being the Makom, for residing with us in the place of our misery and effecting a miraculous redemption. We then continue in our praise, “Blessed is He who gave the Torah to His people Israel, blessed is He.”

God is not only He Who redeemed us from our misery in Egypt but He also gave us, each and every one of us, on that glorious day at Sinai, the all-encompassing code of life we call Torah. All of the sons – wise, wicked, simple and the one too ignorant to know what to ask – regardless of background or temperament stood at Sinai as well. They too are encompassed in the laudatory words introduced by the Ba’al Haggadah to teach the immortal lessons of redemption, “Blessed is God, who gave the Torah to His people Israel. Blessed is He.”

It is the wisdom of Torah to speak of four children; one who is wise and one who is wicked; one who is simple and one who does not even know how to ask a question.

In order to tell, to teach, effectively it is always necessary to speak to where the student is. This is particularly difficult when we are searching for a starting point to effectively communicate Torah values and ideals to the uninitiated, cynical, simple, negative youngster, and yes, sometimes even to the super-intellectual student who believes he “knows it all.” After all, it is all fine and good to include these four children in a single idealistic and laudatory introduction, but quite another to initiate and then engage in a meaningful dialogue with them. It is fine and good for the Rambam to instruct that each son be taught according to his own understanding and abilities. But where to start?

How do we motivate the teacher or parent to even want to engage the child who is simple or negative? How to overcome our reluctance to try and speak with the wicked, or suffer the haughtiness of the intellectual?

Each of these four must, by definition, ask very different questions and each response must be tailored to the question; each response taking into account the difference in attitude, knowledge and experience of the questioner.

Perhaps it will help to recall that we are taught there were a total of four zechuyot, four merits, which together added up to the Israelites’ ultimate redemption and exodus from Egypt. First, there was zechut Avot, the merit of the Fathers. “The God of your fathers appeared to me” followed by the covenant established with the Fathers – “and God recalled His covenant”.

There was the zechut of kabbalat haTorah, the merit of the giving of the Torah. Finally, they merited redemption on account of the Paschal sacrifice and circumcision, which they observed, “and I shall see the blood and pass over their houses.”

The truth is, each of the four sons arrives at our Seder table with his own zechut, his own merit. The commandment to “Tell your son…” There is no qualification for “difficult” sons, or “unwilling” sons. The command is to tell and to teach. Implicit in the commandment is that no Jew is ever closed out of the course of Jewish education; each and every Jew has an inherent right to be taught. Each son arrives with a true claim and right to his share of Sinai. The simple son by virtue of his having been equally present and part of kabbalat haTorah while the one who knows not even how to ask by virtue of his zechut Avot. He may not know how to ask but his father and his father’s fathers undoubtedly did.

It is true that the wicked son has strayed but his claim to the covenant established by God with his fathers is undeniable. Certainly, the wise son calls on all four merits.

The challenge of Sipur Yetziat Mitzrayim is not simply finding a way to teach individual children based on differences in their ages, attitudes, experiences, knowledge and disposition. It is to find in the Maggid experience the voice of sensitive, discerning, and trained educators. Which is to say, to find the good parent within. Finding that good parent, that good father, enables one to seek and find each child’s merit, to establish rapport and dialogue with every type of student.

The Maggid must rely on creativity of heart as much as – or more than – creativity of the mind; commitment, not only skill, love, not merely technique. Any man can tell. Only a discerning, caring, sensitive and giving person can teach.

The commandment expects the first to accomplish the second.

In coming to terms with the dual nature of the command, we consider a well-known question raised in the Haggadah regarding the four sons. As we know, each of the four sons poses the question which defines his nature. However, we find that only three answers are offered – the wicked son and the one who knows not how to ask are give the same answer!

The late Rabbi Yitzchak Hutner explains that there are two basic methods through which the mitzvah of Sipur Yetziat Mitzrayim, of telling of the miracle of our exodus from Egypt, may be accomplished. The first is simply through Haggadah – telling, relating and sharing the story of Egypt. The second involves question and answer, a real give and take between the story-teller and the listener. Rav Hutner argues that the two methods are unrelated and are not necessarily dependent on each other. The Haggadah proclaims that “concerning four sons did the Torah speak, a wise one, a wicked one, a simple one, and one who is unable to ask.” It does not suggest that there is only one method through which to communicate and share the necessary information and knowledge to all four sons.

For the the wise and simple sons, parents and teachers have an opportunity not merely to be maggid, to tell and directly share information and knowledge, but also to provoke and respond to their personal inquiries and curiosities. To the wicked and the one unable to ask, we simply tell it as it is, without anticipation of follow-up questions and reactions. In other words, Rabbi Hutner suggesting, there are many ways to share and teach ideas, ideals and concepts. The task of the maggid in fulfilling the commandment is to discover the appropriate method for each student.

Each Jew then has a right to learn. For each and every one there is an approach through which to be taught – if only we find the compassion and wisdom to discover the individual merit.

Rabbi Dr. Eliyahu Safran serves as OU Kosher’s vice president of communications and marketing. His Kos Eliyahu: Insights into the Haggadah and Pesach (KTAV) has been translated into Hebrew and published by Mosad HaRav Kook.